Tom Weir | West Highland Magic

Tom Weir’s feature on discovering a “passport to wonder” through the West Highland Railway line, republished from a 1960s issue of The Scots Magazine

The West Highland Railway was 70 years old on August 7, 1964. These years have brought many changes to the Highlands — and the universal use of the motor car.

But, for a host of people, the West Highland is still a passport to wonder.

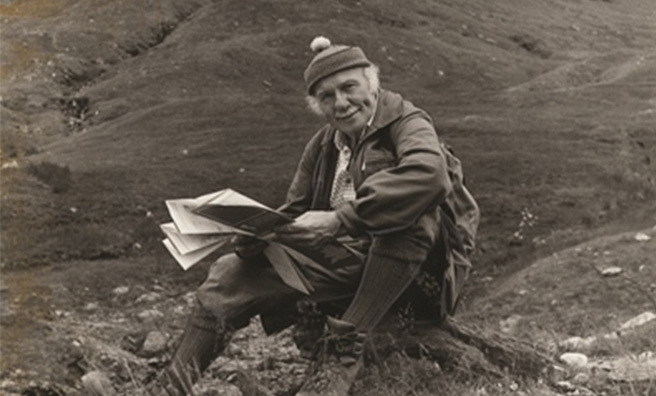

My earliest memory of the West Highland Railway is one of incredulity. Born and brought up in the tenements of Springburn, Glasgow, I was on my way to Spean Bridge to stay on a croft at Stronaba with Andy Gemmell, my school pal.

Andy had told me plenty about the Highlands; how Ben Nevis was so high that you could see the snow on it even in the middle of summer; of salmon throwing themselves out of the rushing river to leap the Mucomer Falls; of the trout we would catch in the burn running past the house where his uncle lived.

What he had not prepared me for was the suddenness of the Highlands, when within an hour of Glasgow we were chugging along the flanks of a steep mountain, looking across to jagged summits pitching sheer into a narrow loch.

Then we were twisting away from its shores and mounting into a green glen seamed with white burns and dotted with sheep, to emerge on the loch again with the tiny houses of Arrochar below us.

I knew nothing about the geography of the landscape, except that where the water had been on our left, Loch Long, it was now on our right, Loch Lomond.

What I did know was an elation which continued to mount as the train ground its way up Glen Falloch into Crianlarich.

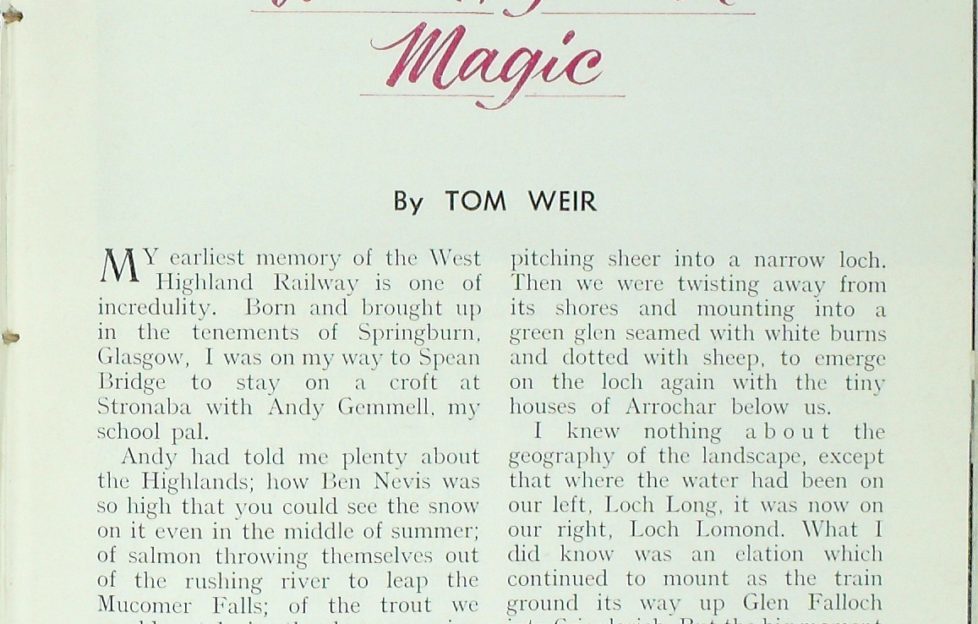

But the big moment was the horse-shoe bend near Bridge of Orthy, as Andy told me to hang out of the open window to see the front end of the train from the back.

There it was, two black engines puffing white smoke, swinging behind them a great arc of red carriages, like a toy poised high above the world.

The thunder of vibrating iron and the dizzy whirl round that great curve in space made a profound impression on this unsophisticated traveller.

Then came Rannoch Moor, which Andy held in awe and communicated his feeling to me as we looked out on nothing but rocks and water.

Here in winter the snow could bury the railway line, and corrugated- iron sheds had to be built over it in one bad place.

Sure enough we plunged into a noisy tin box like a long tunnel, and that was a thrill, though not so much as arriving in Spean Bridge and seeing Ben Nevis, with snow patches on it exactly as I had been led to expect.

I know it must have been a good day because my memory is tinged with the redness of its slopes, which came as a surprise.

Life was never the same for me again.

I knew now what it was to live, as I fished dark pools, felt sharp tugs, and pulled out small trout on my worms.

The days were full, carrying peat from the moors to the house, feeding calves, playing shinty, watching the salmon leap, learning a few words of Gaelic, conscious for the first time of my rightful heritage, that Glasgow was not Scotland, but a place to escape from.

Read the next excerpt from Tom Weir’s

“West Highland Magic” online next Friday!

- Zoom-in for carousel. Scots Mag copyright.