Tom Weir | Chair-lift To Sunshine, Traversing Morven, and A Way With Animals

In April, 1975, Tom Weir skied at Glen Shee, climbed Morven with a friend, visited the new Palacerigg Country Park in Cumbernauld, and still had time to write his monthly column for

The Scots Magazine, describing his adventures . . .

Chair-Lift to Sunshine

It was a long time since I had spent a weekend with Iain and his wife in their Glen Shee house, and as I crunched up the foggy drive in the dark I was surprised to find so much frozen snow lying, for on Loch Lomondside it had been springlike, with the daffodils bursting out and skylarks singing.

“It’s been a miserable week here,” said Margaret. “Thick mist round the house day after day. We should have driven across to you in the West for some of that sunshine you’ve been getting.”

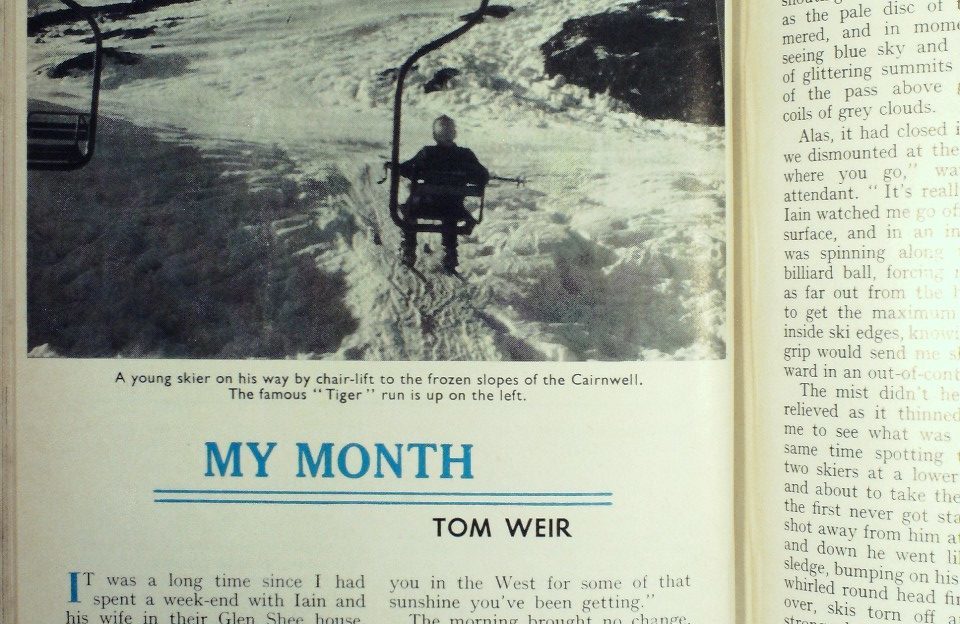

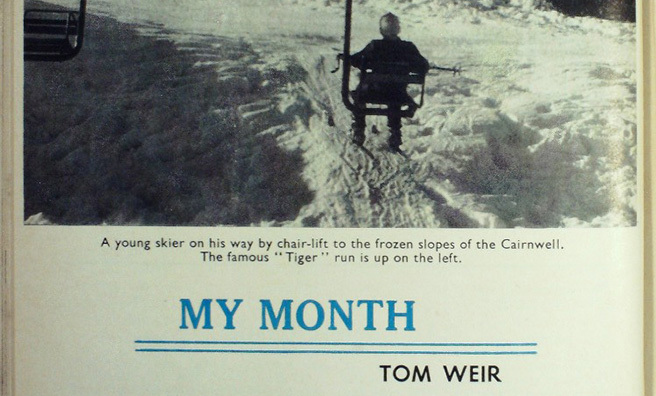

The morning brought no change, but Iain and I had talked about setting off early for a ski-tour, so off we drove into the murk of Cairnwell, surprised at the amount of traffic heading in the same direction – cars, mini-buses, 32-seaters and all the rest. Getting out of the car in the chill mist on top was grim. The only certainty in an intangible world was that the slopes were going to be ice-hard, and a notice on the chair-lift confirmed it, warning all but “experts” off.

“No queues anyway,” said Iain as we took the chair, quilted jackets buttoned up, scarves round our necks and gloves on, to be swung aloft into colder air. Then we were shouting to each other with delight as the pale disc of the sun glimmered, and in moments we were seeing blue sky and jig-saw pieces of glittering summits on both sides of the pass about great snaking coils of grey clouds.

Alas, it had closed in by the time we dismounted at the top.

“Watch where you go,” warned the lift attendant. “It’s really dangerous.”

Iain watched me go off on the glassy surface, and in an instant I felt I was spinning along the side of a billiard ball, forcing myself to lean as far out from the hill as I dared to get the maximum cut with the inside ski edges, knowing that loss of grip would send me shooting downward in an out-of-control glissade.

The mist didn’t help, and I felt relieved as it thinned and enabled me to see what was below, at the same time spotting the shapes of two skiers at a lower angle than I and about to take the plunge. Alas, the first never got started. His skis shot away from him at the first turn and down he went like a runaway sledge, bumping on his bottom, being whirled round head first and turned over, skis torn off and still going strong when he disappeared into the mist.

The second man decided that he was going to take off his skis, and I almost shouted to him not to do so. I didn’t, because I thought he might be merely adjusting the binding. The consideration was academic, for suddenly he was away in a whirl of arms and legs, and I could almost feel his helplessness and bewilderment as he finally disappeared, head first.

Safety considerations sent me side-stepping upwards at that point, an inch by inch labour since each ski had to be placed exactly parallel and at right angles to the slope. Reaching the ridge, I was delighted to meet Iain who had wisely taken the higher line, and in a hundred yards we poised ourselves to take off down the face.

An anxious moment in the first turn, but suddenly confidence flowed and I felt the edges bite in a feeling of control, and my heart sang as turn followed turn and a long, fast traverse shot me from greyness of ice into sparkling snow-powder dancing with crystals. Genuine magic as a corniced gully opened below, and I could swing down its smooth edge, diving down one side of the gully to be carried up the other side on the impetus.

We then made for the ski-tow, and what bliss it was to be pulled uphill in that warm sunshine for fast and smooth downhill runs. The only cloud on my horizon then was the fact that I had forgotten to lift my camera when leaving the house, and could not photograph the dramatic cloud movements as pillows of grey vapour poured over the Cairnwell and lay on the slopes, while we remained in the sun on the edge of two weather systems.

One of the best moments of the day for us came in late afternoon, when, after some grim and icy ski-ing on the Cairnwell side, we went back into the sun on Carn Aosda and took a walk on the tops and found the whole Cairngorm range clear and sparkling from end to end across the Dee Valley. We thought of Adam Watson, who had skied that whole range in a day from Ben Avon to Bein a Bhuird, then over Macdhui and Cairngorm, to retrace to the March Burn, drop to the Pools of Dee and climb Braeriach and Cairn Toul.

We were sorry we had not gone touring as had been our original intention, for this is the true delight of Scottish ski-ing, Now from the sunshine we plunged once more down into mist, and the drive home in the dark had to be taken with care for the fog was thick and Margaret told us it had not lifted all day. We agreed the three of us would go off together in the morning, find the sun, and make a long day of it.

Remembering our view of the Cairngorms and the cloudless Dee Valley, it was very much in our minds in the morning, so the first thing we did was ring Braemar for a weather situation report.

“Warm, sunny, beautiful,” was the answer we got. Nor had we long to wait to find out it was true, for even before we were at the Cairnwell we were in a glittering world of snow edges frozen streams, green grass, grey rocks and the gaudy figures of countless skiers.

I paused on the summit just long enough to take a photograph or two, then down we went into the world of the Dee, with the Caledonian pines outlined against the snows of Lochnagar. I felt I was seeing the Dee Valley for the first time, everything was so finely moulded by shadow and sunlight; the craggy spurs above the windings of the blue river, the bristling trees crowning them, and behind them the great slopes rising to the high snows.

“Why don’t we do something from Invercauld?” suggested Iain. “Explore towards Ben Avon.” Boots on, we took the Gleann an t-Slugain track for half a mile, then struck north for Graig Leek (map on p 68). Grassy meadows, Caledonian pines, the chinking sounds of crossbills, the warmth of the sun and big herds of antlered stags, hinds and calves made the walk across the tops a delight. Margaret had never seen red deer so close, or so unafraid before. You could smell them as we walked along the ridge where they had been moving

“No doubt we smell even more strongly to them,” commented Iain, as we crunched over snow wreaths on our way to Am Bealach and Meall Gorm, where we dropped down to outpost pines and birches to hit a snow-covered track leading to Loch Builg, heather country loud with the cackle of courting red grouse.

We went as far as the Bealach Dearg, to look down on the headwaters of the Gairn. Ben Avon felt very close, but we would have needed all of two hours more to reach its highest top from where we lay in the sun.

As it was, we dozed gently and contentedly, then turned about for the walk back to the outpost pines, enjoying the rose tints on Lochnagar as the west became fiery with sunset. Glen Shee was still filled with frost-fog as we dropped from the Cairnwell summit towards the house, feeling our way carefully as the swirling vapour reflected the rays of our dipped lights, dazzling us.

Traversing Morven

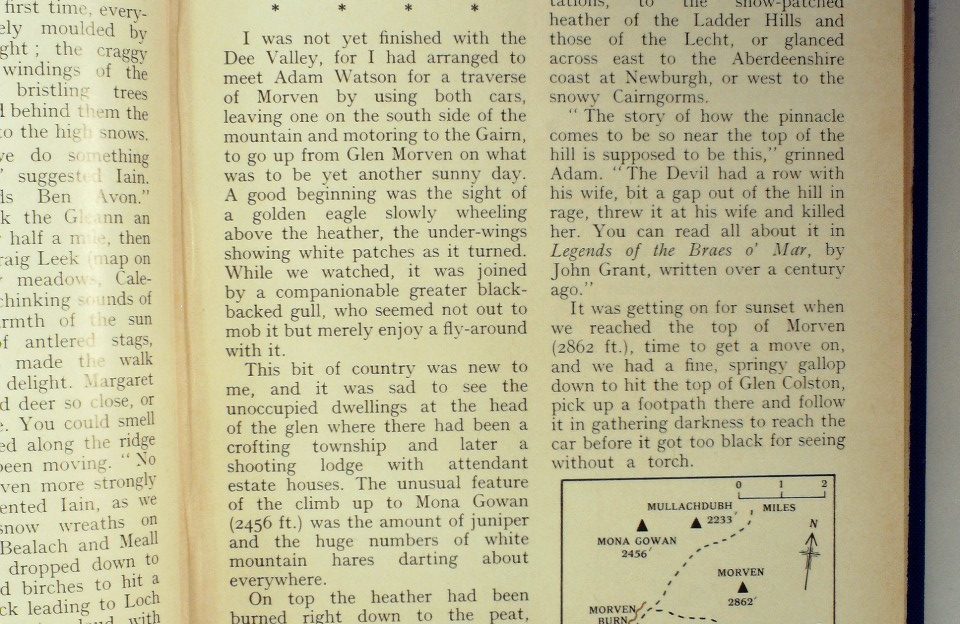

I was not yet finished with the Dee Valley, for I had arranged to meet Adam Watson for a traverse of Morven by using both cars, leaving one on the south side of the mountain and motoring to the Gairn, to go up from Glen Morven on what was to be yet another sunny day. A good beginning was the sight of a golden eagle slowly wheeling above the heather, the under-wings showing white patches as it turned. While we watched, it was joined by a companionable greater black-backed gull, who seemed not out to mob but merely enjoy a fly-around with it.

This bit of country was new to me, and it was sad to see the unoccupied dwellings at the head of the glen where there had been a crofting township and later a shooting lodge with attendant estate houses. The unusual feature of the climb up to Mona Gowan (2456ft) was the amount of juniper and the huge numbers of white mountain hares darting about everywhere.

On top the heather had been burned right down to the peat, leaving a blackened summit resulting from an out-of-control fire.

“You’ll enjoy the next bit,” said Adam as we headed for Mullach Dubh, when we came to a raving that cuts from the glen to the ridge. “The old name for it is Sloc Cailliche, The Gaelic legend is that an old woman known as the Cailleach Bleathrach – the thunderbolt carline – took a bite out of the ridge to try to get the waters of the Don to flow into the Dee.”

The Sloc is certainly unusual, steep-sided, with a pinnacle of rock giving it character. Sitting upthere, we looked across green Strathdon, with its farms and forestry plantations, to the snow-patched heather of the Ladder Hills and those of the Lecht, or glanced across east to the Aberdeenshire coast at Newburgh, or west to the snowy Cairngorms.

“The story of how the pinnacle comes to be so near the top of the hill is supposed to be this,” grinned Adam, “The Devil had a row with his wife, bit a gap out of the hill in rage, threw it at his wife and killed her. You can read all about it in Legends of the Braes o’ Mar by John Grant, written over a century ago.”

It was getting on for sunset when we reached the top of Morven (2862 ft), time to get a move on, and we had a fine springy gallop down to hit the top of Glen Colston, pick up a footpath there and follow it in gathering darkness to reach the car before it got too black for seeing without a torch.

A Way With Animals

Back home to Dunbartonshire, my next jaunt was to the eastern part of my own country to meet David Stephen and see Palacerigg Country Park, Cumbernauld, where he holds the post of Director-Consultant. We had talked about a visit last summer, when the park was formally opened, but on a clear sunny morning 500 ft. above sea level I was glad I had postponed the visit, for David had now much to show me.

“Jump into the car and we’ll have a rattle over the roads first. I should tell you before we go any farther what this place was like before I came. It was a beaten-up sheep farm, over-grazed and ecologically run down, with dilapidated buildings scattered about, giving it a derelict air. When Cumbernauld Town Council bought it and asked me to turn it into an environment for wildlife and recreation, I hardly knew what I was in for. I loved the challenge of course, because it was a chance to put into practice the conservation principles I have been preaching all my life.”

I soon saw what he meant as we threaded a way over the dirt roads and paths leading to little plantations, young hedges and lovely little turfy corners.

“Aye, the turf,” he smiled. “That bit was a mess of dilapidated buildings. We bulldozed the lot, rolled the grounds and put down 1600 square yards of turf. Now it’s a really attractive picnic spot with a fine view of the Campsies.

“We’ve planted over 90 acres of trees, mostly hardwoods. We’ve put in 5000 oaks, and I got some Caledonian pine seedlings from the Black Wood of Rannoch. We’ve really gone to town on hedges – miles of them – with bramble, dogrose and other cover. I put in these wee ponds, and the frogs are spawning in them now. Already, birds that haven’t been here for years are coming back. The grasshopper warbler nested last year. Any day you can see short-eared owls hunting. There are two badger setts just over there.

“There’s something for everybody, the golf course, eighteen holes; the Interpreatation Centre where folk can see the pictures and displays, visit the farm where we have cows and ponies of Scottish breeds, or they can go looking at the deer the badgers, fox, wild cat, polecat, pine marten, quirrels, weasels and all the rest.”

David lives in what was the farmhouse, and just across the way from it is the Interpretation Centre and the animal compounds and car park. “It goes like a fair at the weekends now. You should see the kinds with their binoculars – they keep me busy answering questions and telling me about the birds they’ve see. Come and look at the Centre.”

David’s daughter Cathleen runs it, a girl who learned to say “fox, eagle, badger” almost as soon as she said “Ma” and “Pa”.

“She can tell them the things they want to know as well as I can, and she’s better at handling the sales of the books and stuff.”

The Countryside Commision gave a 75 per cent grant towards the establishment of the park, and money was spared to make this Centre the true hub of the place, with lecture theatre, project room, cafeteria, imaginative displays of pictures and paintings, all in a bright, uncluttered setting.

“It’s amazing,” said David, “the same boys come to look at the same pictures every week, and its always the eagle series.”

We had a look at the captive animals, the big red deer stag which attacked David at rutting time and split his lip so that it had to have stitches to close up the wound,

“Our pair of roe deer had triplets last year,” he told me as we watched the five animals bounding about their large compound. The badgers were underground, but came out when David called them, and immediately “scenting” at his shoe with its musk gland.

I was thrilled by the wild cat “Teuchter”. He was obtained before his eyes were opened, and so he had come to terms with David when he is in the mood. Watching him stalking like a tiger round its den, it had a wild grace I have never seen in a domestic cat, ring tail bolt upright, whiskers stiff and bristling white, the round face and large, yellow eyes alight in arrogance. Of its mate underground I saw nothing, for it refuses to be tamed, and struck out at David when he put his hand to the mouth of the den.

David Stephen used to be a Poor Law officer, and stayed at it until he was 38, when he bought Clayslopes Farm and moved in with his wife, son and daughter, dogs, cats, poultry, stirks, pigs and hens, and began to fulfil himself as a full-time naturalist. Writing and photography were his living, but he shared his home with every kind of animal and everyone who was interested in nature. He discovered early that you get more fun out of life by sharing it with animals and people, and this is what he is doing so magnificently in Cumbernauld.

Check back here next Friday for the next instalment from Tom’s Archives…

More From Tom’s Archives…

- April 1975: Chair-Lift To Sunshine, Traversing Morven, and A Way With Animals