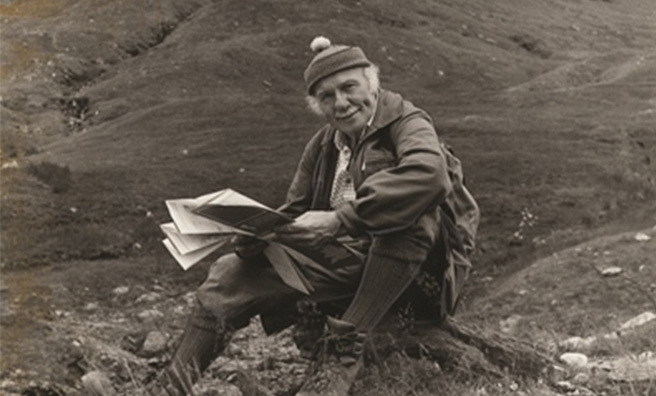

Tom Weir | West Highland Magic Part Five

Tom Weir’s feature on discovering a “passport to wonder” through the West Highland Railway line, republished from a 1960s issue of The Scots Magazine

Part One Part Two

Part Three Part Four

On Post Trains, Changing Tablets, And

The Snow Tunnel On Rannoch Moor

I challenged a spokesman for British Railways on the few parcels being carried on the West Highland Line, and the information he gave me is that parcels are carried at differential rates.

On the busy lines where there is a lot of parcels traffic, rates are cheaper than on lines. The principle of Dr Beeching is that economic routes should not be used to subsidise uneconomic ones.

On the question of freight he admitted a steady decline, but expected busier times when the pulp mill at Corpach comes into operation.

“They have a funny idea of economy,” said one signalman, with feeding. “They tell us the line loses £300,000 a year. Yet look at this station, no electric light. They say it’s uneconomical when there are so few trains a day. I say it’s uneconomic not to have electric light.”

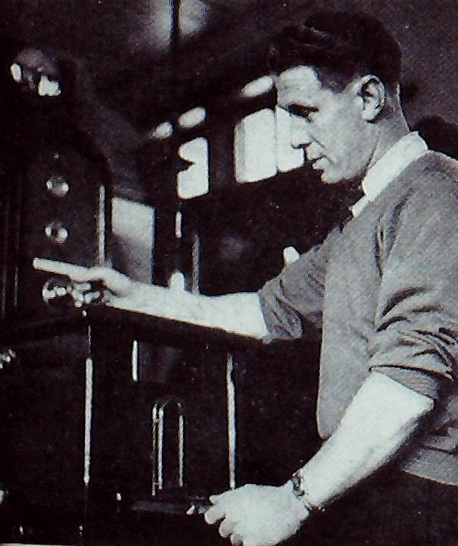

“How do you work the tablet system if you have no electric light,” I asked.

“This way,” he said, sweeping open the doors of a cupboard to reveal rows of wet batteries linked to each other.

This is the source of power which rings the warning bell which is such a familiar sound in West Highland stations.

On receiving four bells, the station master can then turn a commutator knob, and remove a metal tablet, like a packet of cigarettes from a slot machine.

A glance at my photograph will show how he passes it to the driver, receiving in exchange the one carried by the driver.

If for reason there is an electrical failure, then the station master or his deputy must travel on the train with the tablet, this brings the safety factor which ensures that two opposing trains do not meet on a single line.

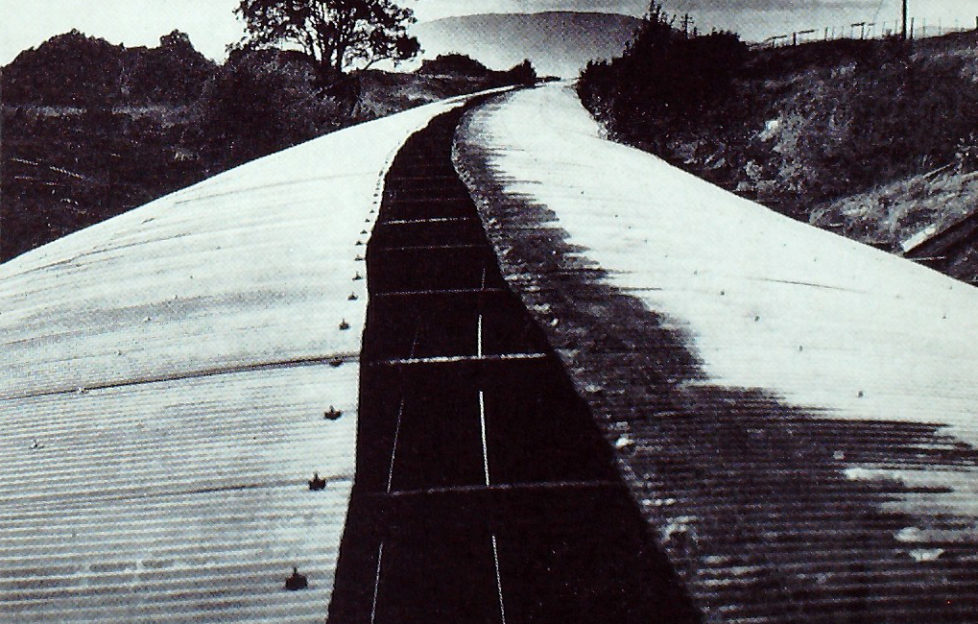

For a railway over difficult country, it is amazing that there are only two tunnels in the 100 miles to Fort William a short one between Arrochar and Ardlui and a longer one of 147 yards at Loch Treig. The snow shed is not a tunnel, but is merely a roof of corrugated iron Iaid on rails along 205 yards of cutting where snow had caused blockages.

When I walked to it in September I found a gap of a couple of feet was laid bare all along its length. This opening is made every summer to reduce strain on the structure.

I was not the only one using the railway line as a highway, for I saw a gang of fishermen with their rods stepping it out to the viaduct where the Gain foams down from Loch Laidon.

They had not travelled up by rail, but by hired bus from Airdrie and Coatbridge, paying only 10s a head for a bus-load of 30.

No railway can compete with that, nor can the railway, with its fixed points of departure, compare with the flexibility of a bus which lifts you from your door and takes you back there.

I also bumped into the preposterous here, when a notice-board caught my eye, looking lonely as a sole spectator at Hampden.

I squelched across to it and read that this three-acre piece of bog was the property of the Nature Conservancv, that it was a reserve representing upland-bog vegetation.

I think the navvies who toiled here would have another name for it.

Read the next excerpt from Tom Weir’s

“West Highland Magic” online next Friday!

- Zoom-in for carousel. Scots Mag copyright.