Tom Weir | West Highland Magic Part 3

Tom Weir’s feature on discovering a “passport to wonder” through the West Highland Railway line, republished from a 1960s issue of The Scots Magazine

Click here for part one

Click here for part two

The Fort William section of the railway was opened only 20 years before I was born, and not until seven years later, in 1901, was the Mallaig extension open for traffic, which shows how little sense of history a boy born in 1914 had.

Indeed I was unaware that I was in the presence of history when, as I made my first journey in July 1929, the waiter came along and asked “Anyone taking lunch?”, for not until that month had the West Highland carried a dining car.

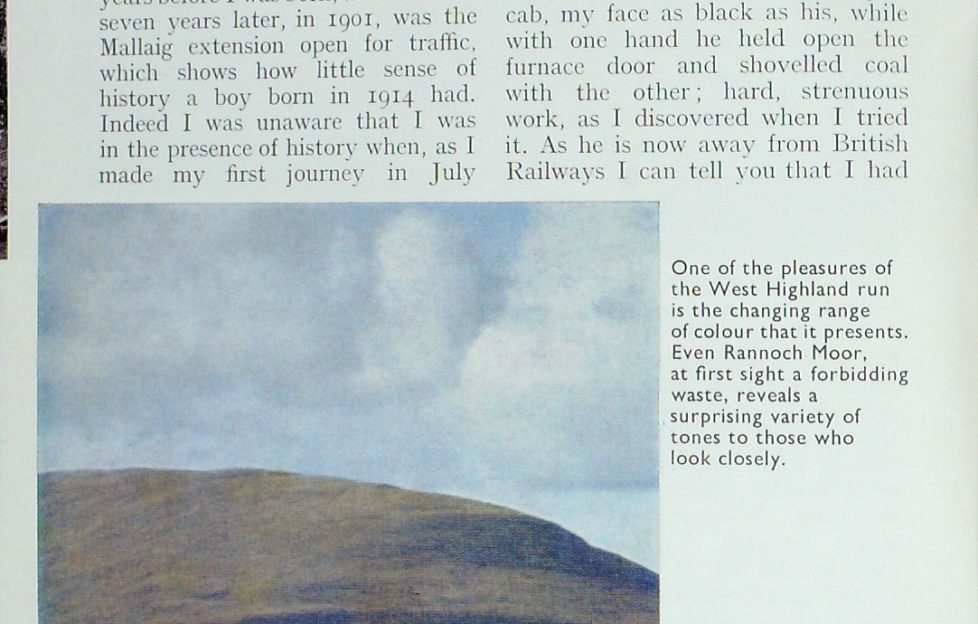

Nor did I realise as I rattled through the snowsheds of Rannoch Moor that I was passing through the only thing of their kind in Britain.

It was John MacNair, the Arrochar cleaner, promoted to fireman and spare driver, who wakened me to lots of the features I was missing.

For I travelled with him in the engine cab, my face as black as his, while with one hand he held open the furnace door and shovelled coal with the other; hard, strenuous work, as I discovered when I tried it.

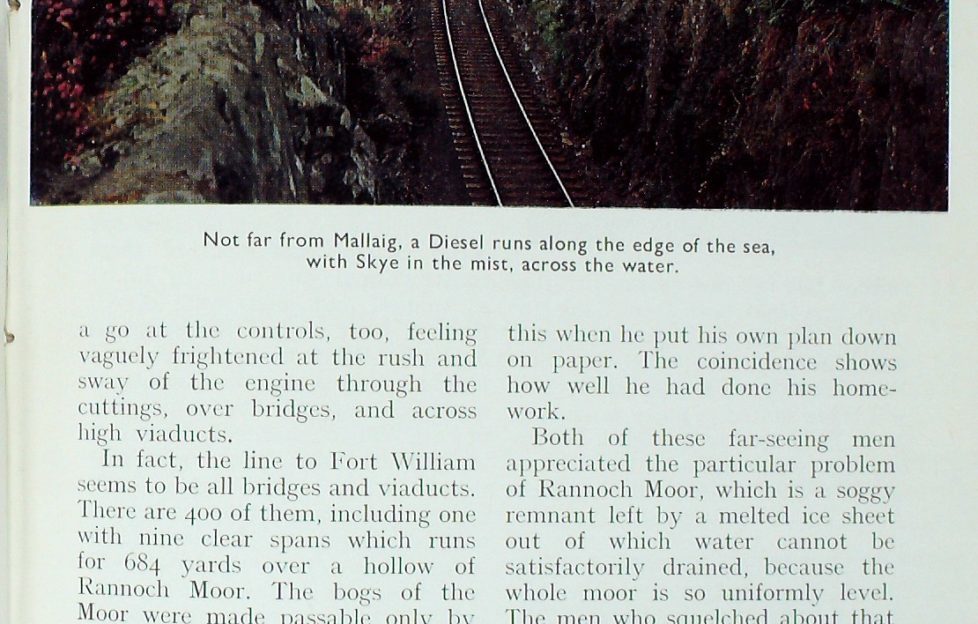

As he is now away from British Railways I can tell you that I had a go of the controls, too, feeling vaguely frightened at the rush and sway of the engine through the cuttings, over bridges, and across high viaducts.

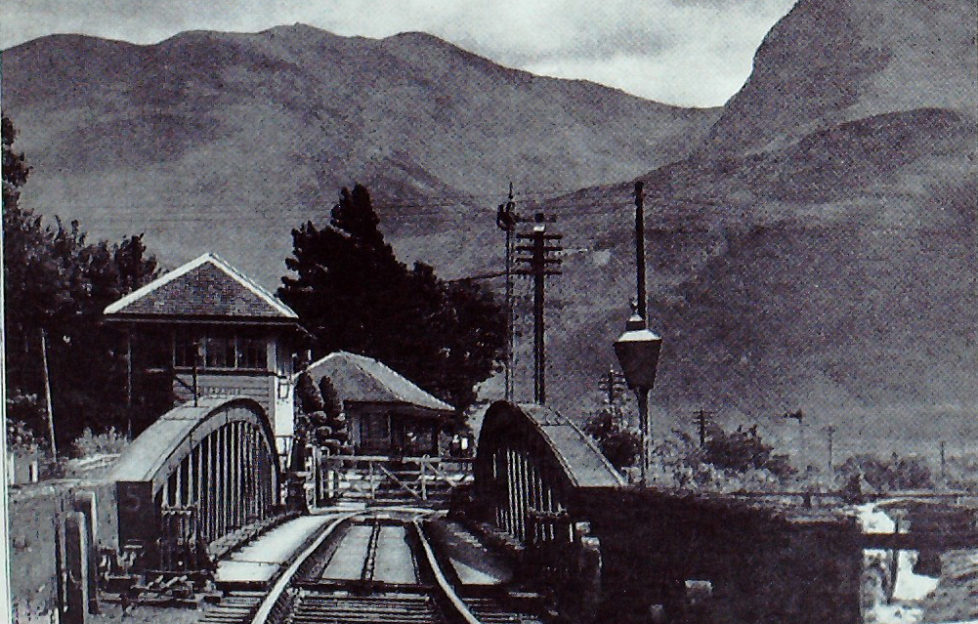

In fact, the line to Fort William seems to be all bridges and viaducts. There are 400 of them, including one with nine clear spans which runs for 684 yards over a hollow of Rannoch Moor.

The bogs of the Moor were made passable only by collecting tree roots of former forest and overlaying them with a covering of brushwood, then building a foundation of rocks and excavated material, on top of which went thousands of tons of ashes to take the permanent way.

The route finally chosen for the railway follows almost exactly the line for a road proposed by the great Thomas Telford, though Charles Foreman, the railway engineer responsible, did not know this when he put his own plan down on paper. The coincidence shows how well he had done his homework.

Both of these far-seeing men appreciated the particular problem of Rannoch Moor, which is a soggy remnant left by a melted ice sheet out of which water cannot be satisfactorily drained, because the whole moor is so uniformly level.

The men who squelched about that soggy mattress, building the line, must have felt real ” Children of the Dead End,” with no road or village to break the desolation.

Few could stick it for long, yet the whole hundred miles of line from Craigendoran to Fort William took only four years and ten months to build, good going for 2000-5000 men.

It so happens that my first foot- slogs on Rannoch Moor brought me face to face with the fact that the railway had not just grown with the landscape, that both were liable to change, as gangs of navvies were demonstrating at each end of Rannoch Moor.

For the railway line was being shifted to make a dam at Loch Treig for the Lochaber Power Scheme, while on Black Mount hundreds of men were driving the £6,000,000 Glen Coe road.

I felt I knew what it must have been like to build the railway line when I took shelter in the navvies’ camp and an Irishman lent me dry clothes while my wet ones were hung up before the stove, its red- hot pipe shaking in the blasts of rain hurled against the hut.

Read the next excerpt from Tom Weir’s

“West Highland Magic” online next Friday!

- Zoom-in for carousel. Scots Mag copyright.