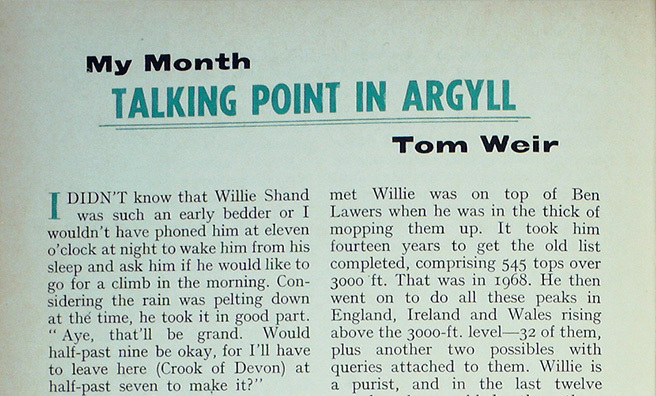

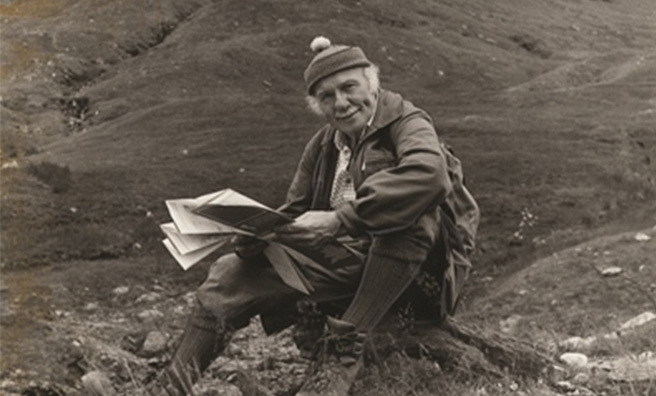

Tom Weir | Talking Point in Argyll

Tom Weir and fellow adventure writer Willie Shand explored glorious Loch Goil – and debate the newly constructed caravan park

I didn’t know that Willie Shand was such an early bedder or I wouldn’t have phoned him at eleven o’clock at night to wake him from his sleep and ask him if he would like to go for a climb in the morning. Considering the rain was pelting down at the time, he took it in good part.

“Aye, that’ll be grand. Would half-past nine be okay, for I’ll have to leave here (Crook of Devon) at half-past seven to make it?”

And he was bang on time on a not very good morning. Spreading the map out on the table, I put my finger on a peak called Cruach nam Miseag on the west shore of Loch Goil.

“How about that? I’ve never been on it, but I’ve admired it often enough.”

“Great,” said Willie. “It would be new to me, for I’ve never been in that country at all.”

I laughed.

“I didn’t think you would have been where there are no Munros.”

The purist of Munro baggers

The first time I had met Willie was on top of Ben Lawers when he was in the thick of mopping them up. It took him fourteen years to get the old list completed, comprising 545 tops over 3000 ft. That was in 1968.

He then went on to do all these peaks in England, Ireland and Wales rising above the 3000-ft. level — 32 of them, plus another two possibles with queries attached to them. Willie is a purist, and in the last twelve months has added the three additional Munros in the revised Scottish list of 280 Munros and 542 tops.

He was recalling these happy times as we drove over from Loch Long to Loch Goil by the Rest and Be Thankful, to swing down Glen More.

“This is marvellous. I had no idea there was anything as good up here,” he enthused as we dropped steeply down on the dangerously twisting single track to sea level.

There, ahead of us, was our peak rising above Douglas Pier.

We agreed that the most interesting way would be to take it from the south-east by Cormonachan Glen, a fine route up a burn of waterfalls tumbling down through an oak wood, then into a tangle of conifers, ditches and small trees.

Falcons at play

The angle was steepish, but we were making height on the rough when suddenly we stopped at the sight of two sharp-winged, long-tailed birds beating across the rocky ridge immediately ahead of us. They were climbing higher and higher, then – Whoosh! – the first one went into a power dive, wings folded back behind broad shoulders. As it straightened out, down came the other, to climb high after its mate and repeat the acrobatic performance.

They were peregrine falcons, and hoodie crows hurled abuse at them and tried ineffective pursuit, but they might have been standing still compared with the speed of the rocketing falcons.

After a pech through a bracken jungle we struck the ridge, nice airy walking with wee rock scrambles and a view that was getting better and better every few minutes.

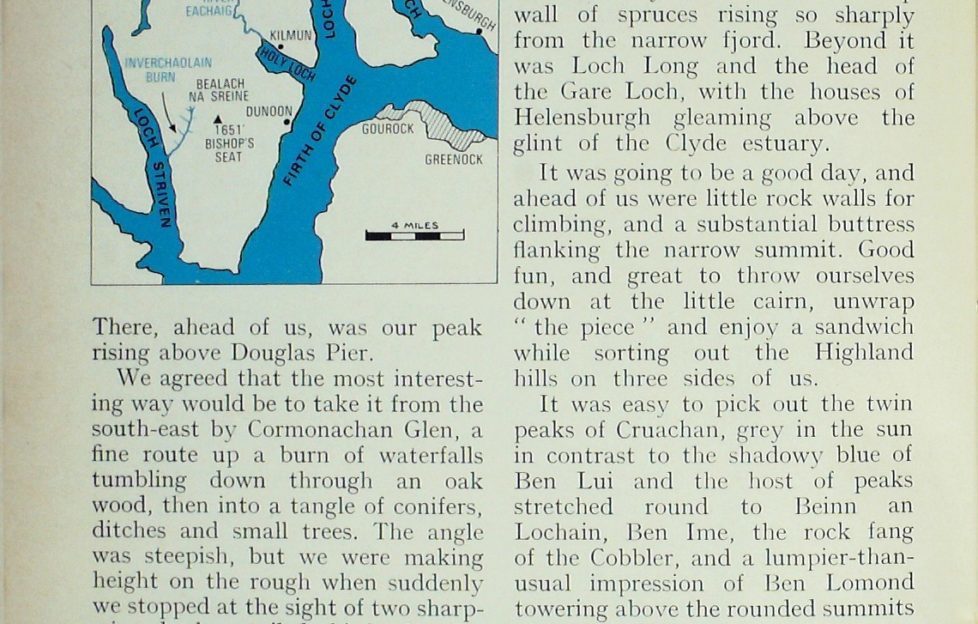

Below us now was the roadless spine of rocky tops of Argyll’s Bowling Green, rising above timbered slopes running the whole length of Loch Goil, a view almost Norwegian in character by reason of its steep wall of spruces rising so sharply from the narrow fjord. Beyond it was Loch Long and the head of the Gare Loch, with the houses of Helensburgh gleaming above the glint of the Clyde estuary.

It was going to be a good day, and ahead of us were little rock walls for climbing, and a substantial buttress flanking the narrow summit. Good fun, and great to throw ourselves down at the little cairn, unwrap “the piece” and enjoy a sandwich while sorting out the Highland hills on three sides of us.

It was easy to pick out the twin peaks of Cruachan, grey in the sun in contrast to the shadowy blue of Ben Lui and the host of peaks stretched round to Beinn an Lochain, Ben Ime, the rock fang of the Cobbler, and a lumpier-than-usual impression of Ben Lomond towering above the rounded summits of the Luss Hills.

But Willie’s eyes were on the Cowal peaks stretching to Loch Fyne, all of them strangers to him, but easily accessible to me in my teenage days when train and steamer excursions brought them within cheap range. I pointed out Ben Mhor to him and the ranges southward extending to Bishop’s Seat— favourites of ours in the 30s.

The early climbers were favoured by better public transport services than exist now.

Climbing in bygone days

Leaving Glasgow at 7 p.m., we could be disembarking at Kilmun or Dunoon and stepping on to a bus with a choice of excellent ways. A favourite was to walk from the head of the Holy Loch following the River Eachaig through the Benmore policies and up the lonely west shore of Loch Eck, the destination an empty house called Bernice which was a good ” doss,” reached about 11 p.m. after an eight-mile tramp.

Morning would see us on Ben Mhor, rock-scrambling on the face which is enlivened by some pinnacles. And my friend Matt would be telling me things about the Clyde for which he had a passion; of the great engineer David Napier who built Kilmun pier and not only opened the Clyde to tourist traffic in the early 19th century, but put the first iron-hulled steamer in Scotland on Loch Eck.

This Napier was the man who cast the boiler for Henry Bell’s Comet, and in retirement after a brilliant career went to live at the head of Loch Eck.

I should have started my hill-walking sooner,” said Willie as I enthused on Loch Striven and the hills on each side of the Bealach na Sreine which Matt and I could reach easily by climbing through Glen Kin from the head of the Holy Loch and camp in true isolation high up the Inverchaolain Burn. Even today the western half of Cowal is still a lonely place, and I remember the thrill of finding my very first golden eagle’s eyrie under an overhang of rock. The bird had flown out below us, and when I peered over, there was my very first black-and-white eaglet.

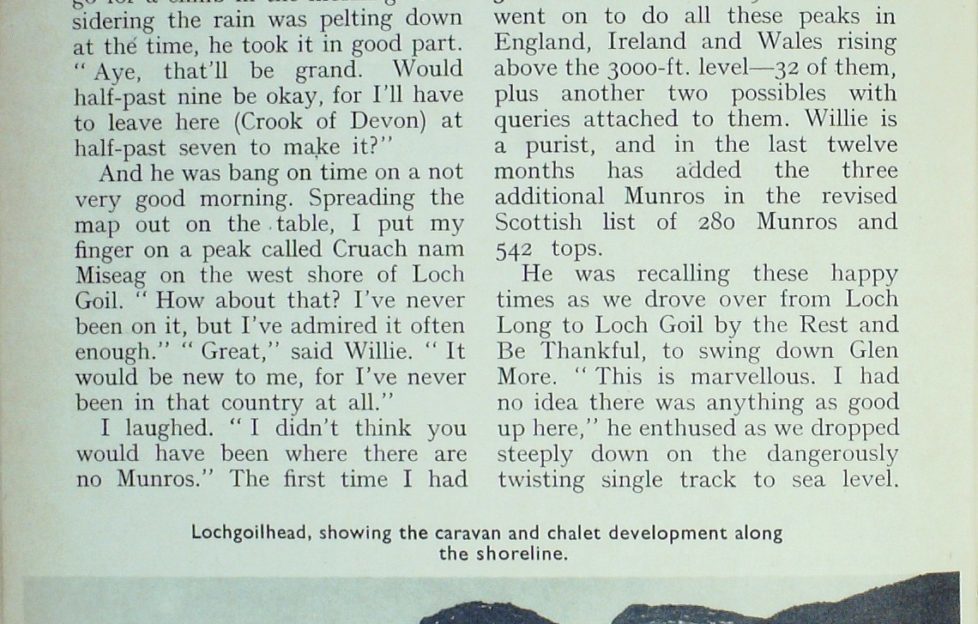

“I’m coming back here,” said Willie as we left the top, traversing north to trv a different route of descent, down rocks and into the deep cleft of a ravine. Lochgoilhead was only a thousand feet below us now, and, as the sunshine lit it for the first time, we sat down to enjoy the rocky setting of the deep-set loch, undoubtedly one of the finest in Scotland.

I was waiting for Willie to make some comment on the immediate foreground, and it soon came.

“That’s as good a view as you could ever see, but that solid row of chalets and caravans spoils it. Why don’t they screen it? It’s horrible!” he exclaimed.

I suggested we go and look at it close up and I would tell him what I knew about it.

“You’ll find it’s very nicely landscaped,” I said, giving him no clue that I hated the sight of it as much as he did. “You must agree, it’s well kept — the grass has all been cut. Look at all the boats out there in the bay. It’s a lovely place to come to at week-ends and sail your boat. What’s wrong with it?”

He didn’t mince his words

“It’s quite out of character. Every chalet is the same as the next one. And these hundreds of caravans, without a bit of screening! I thought we were supposed to have some planning in this country? I’ve been all over the Highlands and I’ve never seen anything worse on a sea loch.”

I told him that the man who owns it, and has the lease of most of the shore between here and the end of the road at Carrick, had applied to fit in another 28 chalets on the site, and that the building under construction at the side was to be a supermarket. Also that a small rash of new bungalows along the shore are all part of the same “Campbell’s Kingdom” as the locals describe it—Campbell being the name of the enterprising owner.

Back at the car we drove to the end of the road, stopping for a picnic on a gravelly bay with eider ducks and mergansers for company, and a passage of dinghies and yachts moving elegantly against the roadless peninsula of heather and rock which is the eastern shore of Loch Goil. In times past the drovers walked their cattle across that spine of hills, descending to Loch Long to be ferried over from Mark to Portincaple.

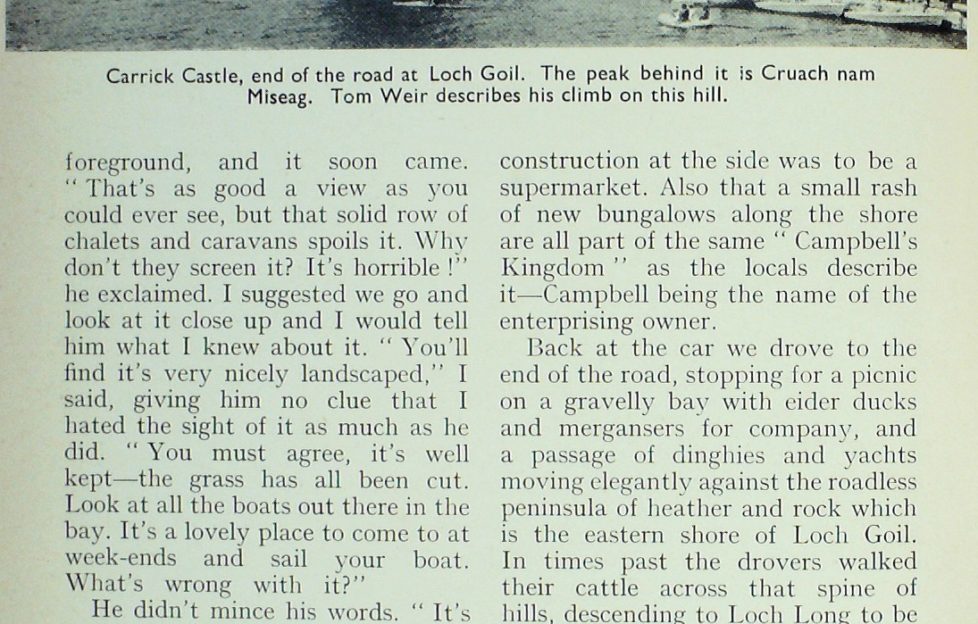

Carrick Castle made the perfect foreground for the peak we had just climbed. In the 15th century the Lamonts had it before it passed to the Argyll Campbells. Carrick springs from the Gaelic for rock. It’s perched on a rock reached only by draw-bridge when it was in use.

Cromwell besieged it in the 17th century, but it was the Murrays of Atholl who devastated it and took away 119 horses, 330 cattle, 188 sheep. I am surprised it has not been restored, for it is in fair order. Wall-climbers were perched on top of the battlements looking down on an activity of canoeists, yachts and tourists.

Probably the less said about the architectural development around Carrick Castle the better. They are the product of 100 years of poorly designed buildings plus another chalet development. Will and I turned for home after this, but I went back to the castle a fortnight later to take a closer look at the Argyll Forest Park.

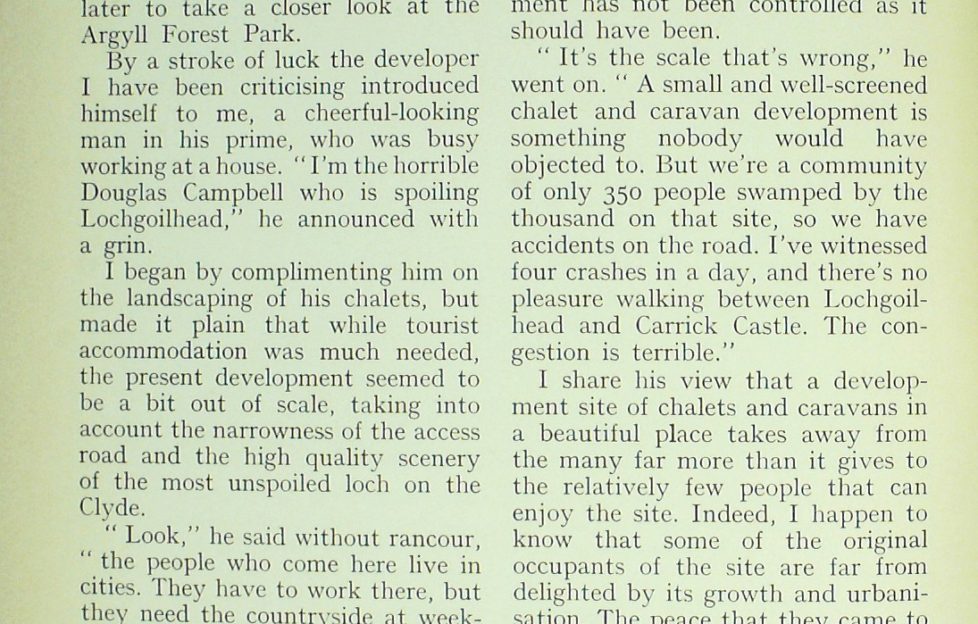

By a stroke of luck the developer I have been criticising introduced himself to me, a cheerful-looking man in his prime, who was busy working at a house.

“I’m the horrible Douglas Campbell who is spoiling Lochgoilhead,” he announced with a grin.

I began by complimenting him on the landscaping of his chalets, but made it plain that while tourist accommodation was much needed, the present development seemed to be a bit out of scale, taking into account the narrowness of the access road and the high quality scenery of the most unspoiled loch on the Clyde.

“Look,” he said without rancour, “the people who come here live in cities. They have to work there, but they need the countryside at weekends. They come here for peace and scenery, and to sail their boats. Is there anything wrong with providing for their needs? You can’t stop them coming, so you might as well prepare for them. Restrict them and all you would have is a handful of retired people living here.”

I put his viewpoint to W. H. Murray, conservationist and author, who lives at Lochgoilhead.

“I can quote to you,” he said, ” the findings of the Scottish Countryside Activities Group which comprises spokesmen from all clubs and organisations having outdoor interests. It states: ‘ The chalet and caravan developments on Loch Goil are the most obtrusive in Scotland in an area of high landscape value.’ The trouble is that the Forestry Commission gave the developer a 40-year lease of land with no strings attached. That was in 1964, when the Argyll County Council planning staff was one man and a boy, and the development has not been controlled as it should have been.

“It’s the scale that’s wrong,” he went on. “A small and well-screened chalet and caravan development is something nobody would have objected to. But we’re a community of only 350 people swamped by the thousand on that site, so we have accidents on the road. I’ve witnessed four crashes in a day, and there’s no pleasure walking between Lochgoilhead and Carrick Castle. The congestion is terrible.”

“Hold, enough!”

I share his view that a development site of chalets and caravans in a beautiful place takes away from the many far more than it gives to the relatively few people that can enjoy the site. Indeed, I happen to know that some of the original occupants of the site are far from delighted by its growth and urbanisation. The peace that they came to find is disappearing. There comes a time to cry, “Hold, enough!” and that cry should be heard now. Let us hope that some firm control can be exercised on future developments.

No doubt the Forestry Commission regret that they did not attach strings to their lease of the shore-line between Carrick and Lochgoilhead, for they have done a very great deal of recreational good with their 103 square miles stretching from Loch Long to the hills above Loch Eck and the Holy Loch. One bit that is not inside it is the hill region above Castle Carrick.

“Because I wouldn’t sell it to the Forestry Commission,” said Peter Ferguson, who runs sheep over the 2000-ft. tops of Cruach a’ Bhuic. “There’s mair nor enough forest as it is, and I’ll no deny they’ve done a fair job, but ye can overdo the trees.”

As I spoke to him, his shepherd, Michael Griffin, was working his dog bringing in some sheep and lambs. What a performance! I’ve seen many working sheepdogs in my time, but never one which answered the whistles and commands more perfectly, as it took the flock in a run towards the shepherd, then as they slowed down, quartered the flock back and fore until they came to a stop in front of the shepherd.

“Aye, we’ve been on the tops gathering to pick some for the sales at Stirling,” Michael explained as he let the unwanted ones go. When I complimented him on his dog, he smiled. “It’s totally blind in one eye. But it’s good. It’s done well at the sheepdog trials, including the National Championships. But I’ve got a pup that’s going to be even better.”

It was to be my day for meeting people, for when I talked to a forester he told me his name was John Grieve and that I had taken his photograph once at Crinan.

“You sent me one and I’ve still got it,” he laughed. He was climbing up to see some of his men busy thinning 20-year-old timber in the heart of the forest, and he presented me with a fibre-glass hard hat to put on my head when I said I’d like to come up with him.

A few hundred feet up a steep ride in the spruces and we were in full sound of the rasping power-saws, a scene of activity as men brashed away the branches of fallen trees and laid low 40-footers which were no sooner down than the branches were being shorn off and the tree measured by tape to be cut into the exact lengths for pulping at Corpach.

I admired their expertise on uneven ground, awkwardly cut up by drains and littered with branches. Helmeted and wearing protective goggles, ear-muffs, leather gloves and protective boots, the men explained to me why the gear was necessary.

The wood chips spattered out by chain-saws can damage the eyes. The ear-muffs take away the dis- comfort of noise, the gloves protect the hands from abrasion, and the boots would save your feet if the chain-saw slipped on to them. In the event of a stumble on the uneven slopes, the saw itself has a safety handle for switching off the power.

After that pleasant interlude I was introduced to Arthur Robinson, newly back from the hill after bringing home two red deer stags to the Forestry Commission larder at Ardgartan.

“They’re not very good beasts, just part of the necessary cull to keep stag numbers within bounds or there would be too many of them for their own good as well as ours.”

A forest ranger who loves the outdoors, Arthur explained why he was home so early. “I’m always out before dawn. It’s the bit of the day I wouldn’t miss. That’s the time to be out. Men are asleep, but nature is awake and you see things then you’ll see at no other time. I go out before dawn every day of the year.”

A man after my own heart.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday.

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here for Tom’s online archives.