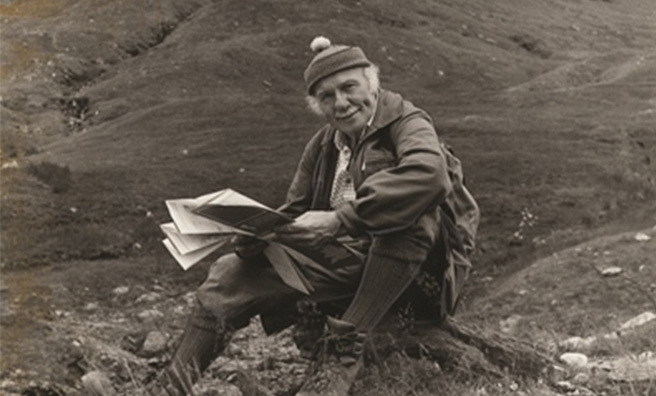

Tom Weir | The First “My Month”

After writing occasional freelance features for

The Scots Magazine for several years, Tom Weir was finally given his own column in April 1956

The “My Month” series lasted for over 50 years, and is still popular today with his columns finding a new audience through our online archive.

We’ve just produced our April 2016 issue, and thought it fitting to reprint Tom’s first column (complete with an introduction by the editor of the day) on the series’ 60th birthday:

Tom Weir, climber, explorer, student of Scotland and its wild life, writes the first of a new series. Each month he will describe his experiences on Scottish hills, telling of people he has met and giving his views on topics of the moment. Mr Weir will be glad to put his experience at the disposal of readers who wish his advice on mountaineering and kindred recreations.

Queries should be addressed to Tom Weir, c/o Scots Magazine, 7 Bank St., Dundee.

Note: our new address is The Scots Magazine, D C Thomson & Co Ltd., 1 Albert Square, Dundee, DD1 1DD. We would be glad to read your letters or comments.

A Strange Experience In Glencoe

First published in The Scots Magazine’s April 1956 issue

GHOSTS ; haunted houses ; do you believe in them; or, like me, do you think they are largely creations of the imagination, of high-strung nerves, of darkness or loneliness?

I thought I had become blasé about supernatural things, but I must tell you of a strange experience which befell two of us in Glencoe, or to be more exact the offshoot of it called Glen Leac na Muic.

We had tramped up the glen hoping we would find a barn to sleep in and not have to pitch the tent. Bob reckoned he knew a place, and sure enough, round a bend in the path we saw the glimmer of light from a shepherd’s cottage, the only one in the glen.

“Ay, take the barn, but don’t set it on fire,” said the shepherd, “but what you want climbing hills in the snow beats me.”

The voice was gloomy and pessimistic, but not unfriendly. The barn was a snug little place, about a hundred yards away from the house, and we were soon settled in the hay, inside our sleeping bags, listening to the wind moaning outside—glad indeed, that we were not camping.

A Face Like Clay

It would be somewhere in the middle of the night that I awoke with Bob shining his torch in my face, in a considerable state of excitement.

“There was a man at that door a moment ago,” he said, “with a face like clay. He was standing there, but he didn’t speak, and when I shone my torch he disappeared.”

“How could you see a face like clay in pitch darkness?” I said. “Don’t be daft. You’ve been dreaming. Go to sleep.”

“I’m telling you, Tom, he was there. A man with a face that had no blood in it, but there was blood on his clothes. The eyes were like sunk-in holes. It wasn’t a dream. I’m sure of it.”

And to my surprise he was still talking about it next day as we climbed Sgur na h-Ulaidh on a foul day of driving snow, made suddenly worth-while when, on the summit, there was a sudden tear in the clouds and we looked for an instant on vast, snow-covered mountain- tops, plunging into glens of impenetrable depth.

Then the black slashes of sea lochs and ocean were swallowed up again in the turmoil of storm, and we had to fight our way off the mountain, heads down to the storm.

It was late afternoon, and we were changing out of our iced clothing and frozen socks in preparation for making a meal, when the shepherd appeared.

You had better come down to the house and sit at the fire,” he said. “It’s too cold here to be cooking, and yourselves half-frozen.” We were only too pleased and were soon made free of his fire-place.

The shepherd was a man of few words.

“How did you sleep in the hay?” he asked. I said, jocularly, that my friend had been seeing a ghost, and told the story of the appearance at the door of the man with a face like clay.

He did not laugh. Instead he gave me a penetrating look.

“Well,” he said, “you know what happened at this spot?”

” To do with the Massacre?” we both asked.

“Yes, to do with the Massacre,” he answered. “It was on the spot where the barn stands that MacIan, the chief of the clan Macdonald, was murdered 264 years ago; and I am thinking that the man with the face like clay you saw was the ghost of the chief.”

What do you think?

Scotland’s First Ski Tow

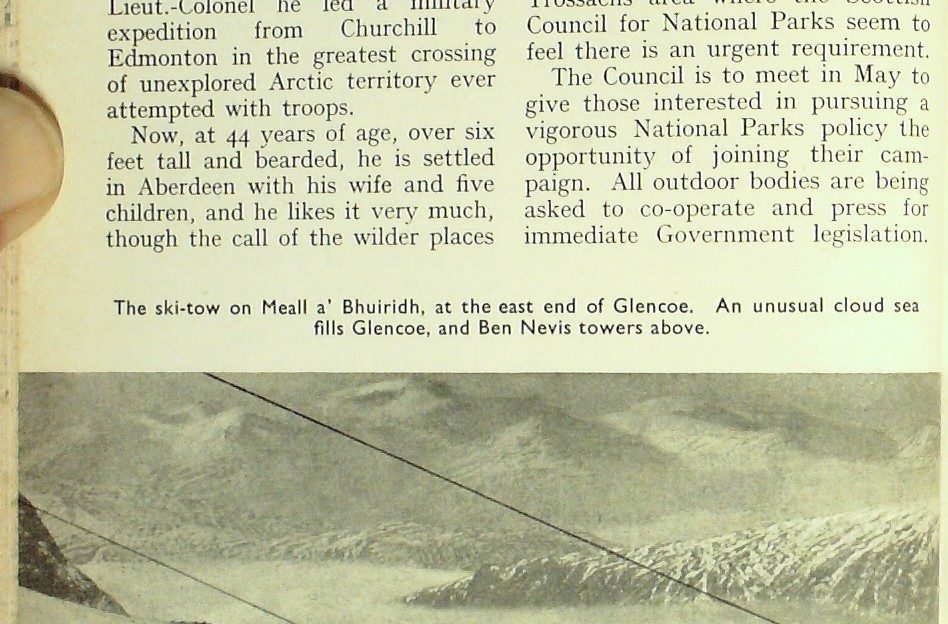

Coincident with the anniversary of the Massacre this year was the inauguration of Scotland’s first Continental-type ski-tow, now operating every week-end on Meall a’ Bhuiridh, and attracting skiers from as far south as Bradford and London.

Already the Hill of the Roaring Stags can be more properly described as the Hill of the Roaring Skiers, and hotel keepers in the district reckon they are in for a new era of prosperity in the off-season of February, March and April.

The day I was up I counted over 400 skiers on the slopes, and in the space of three hours one or two people had managed to put in some 10,000 ft. of downhill running in the snowy corrie.

The lift is 900 ft., and theoretically 250 skiers per hour can be transported uphill, though it has not worked at that capacity yet owing to certain teething troubles. Cost per journey is 2s 6d to members and temporary members of the Scottish Ski Club. This should do much to raise the standards of ski-ing in Scotland.

A Man Of Interesting Personality

Every month in this diary I hope to bring you some interesting personality. The man I would like you to meet this time is Pat Baird, of Caithness and Canada.

The originality of a man’s ideas gives a fair clue to his character, so when I tell you that Pat Baird’s idea was to put a weather station on the remote peak of Ben Macdhui and visit it every ten days or so for the purpose of getting records of temperature, wind speed and relative humidity, you can gather that this is a very exceptional man.

The idea came to Baird in the course of his work as a research geographer; the Nature Conservancy backed it; and disregarding the advice that December was not the time to start transporting a quarter of a ton of equipment up a 4000 ft. peak, he began it, sleeping in a hut on the hills, and going on skis and on foot to work on the windiest plateau in Scotland. Now, in late February the first hill-top Observatory since Ben Nevis is working.

What is it for, you will want to know. Primarily to study growth and wastage of the Cairngorm snow beds in relation to their meteorological environment – a study of some importance to Baird, for the structure and composition of glaciers and ice fields has taken him six times to the Fast Canadian Arctic. He feels there is much of fundamental importance to be learned from the behaviour of the semi-permanent snow beds in the Cairngorms, not to mention the vegetation under the snows that sees the sunlight only once in ten years or so, yet manages to survive.

A research geographer and geologist, Baird has had an adventurous career. He went to Canada in 1936, became a specialist in mountain warfare during the war and trained troops in Iceland, the Cairngorms and in Canada, where as Lieut.-Colonel he led a military expedition from Churchill to Edmonton in the greatest crossing of unexplored Arctic territory ever attempted with troops.

Now, at 44 years of age, over six feet tall and bearded, he is settled in Aberdeen with his wife and five children, and he likes it very much, though the call of the wilder places will probably take him back to Canada when his work at Aberdeen is completed.

On National Parks…

How do you feel about National Parks in Scotland? Do you think we need them, or are you quite happy the way things are now?

Ten years ago I was a fierce advocate of them, but since that time the country has become so much freer to the public that I cannot see any real need for them— especially in the Loch Lomond- Trossachs area where the Scottish Council for National Parks seem to feel there is an urgent requirement.

The Council is to meet in May to give those interested in pursuing a vigorous National Parks policy the opportunity of joining their campaign. All outdoor bodies are being asked to co-operate and press for immediate Government legislation.

The aims of the Scottish Council for National Parks are better footpaths, better cross-country routes, litter control, and protection of amenities. Mr W. A. Nicholson, of the Scottish Tourist Board, has been quoted as saying, “There should be absolutely no restrictions, but full freedom for camping, walking, and all recreational pursuits.”

The doctrine of “absolutely no restrictions” would bring chaos to Loch Lomondside and the Trossachs in no time, just as the same principle would destroy the public parks in the larger towns.

No, I agree with the National Trust for Scotland, who take the line that the need for National Parks is not sufficient to justify the expense they would incur—not when we have such magnificent and ably managed Forest Parks as Glen More, Glen Trool, Argyll, and the more recent Queen Elizabeth National Forest Park which includes Ben Lomond and the best of the Trossachs.

Then there is the Nature Reserve in the Cairngorms, comprising over 40,000 acres of magnificent territory open to anyone who cares to go— not to mention the heritage of Glencoe, Dalness, Kintail and Ben Lawers—mountain regions which are ours for all time with absolute freedom of access.

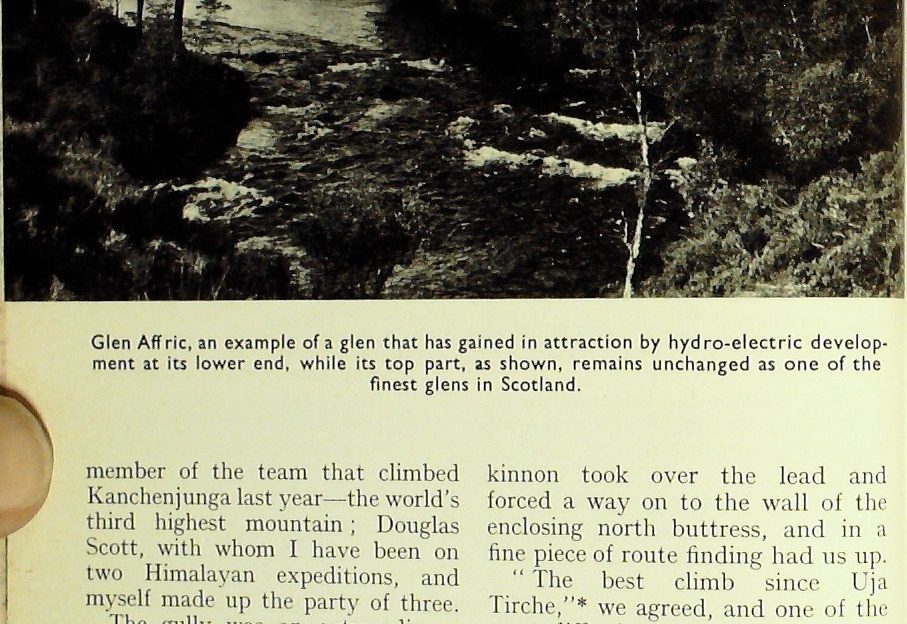

I would like to mention, while on the subject, the fine work done by the Hydro-Electric Board in opening up such areas as Glen Affric and Cannich—in some cases making the lochs more beautiful by wise engineering, and certainly making them much more accessible by providing good roads.

And we must admit, whatever our views about private ownership of land, that most estate owners are responsive to good behaviour. I have had trouble with landowners and their keepers in the past, but not in the last decade. We live in an age of enlightened landed proprietorship, as we may see any week-end on Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, with tents everywhere, and the hills open to all.

Who suffers by there being no National Parks in Scotland? My answer is “No one.”

As Wild As The Himalayas

Knowing that I have climbed in many big mountain ranges of the world, people often say to me, “Of course Scottish mountains won’t be very much to you “—meaning that the climbing we have at home here is child’s play.

How wrong they are was demonstrated one day in February. Then three of us climbed the Crowberry Gully of Buachaille Etive Mor and spent over 10 hours getting up it, and some 3 ½ hours in darkness getting down off the mountain.

This gully, which is a narrow slip of 1000 ft. separating two of the biggest mountain walls on the Buachaille, gives a difficult rock climb in summer. In February it is usually a major expedition involving the climbing of walls of solid ice out of which one has to hack hand and foot holds.

Tom Mackinnon, who was a member of the team that climbed Kanchenjunga last year—the world’s third highest mountain; Douglas Scott, with whom I have been on two Himalayan expeditions, and myself made up the party of three.

The gully was an extraordinary sight — a narrow ribbon running between vertical walls—the line of ascent running up over hanging-chandeliers of icicles and over rock slabs sheeted in ice thicker than ships’ plating. One icy slab of 100 ft. took two hours to climb.

Then at dusk it looked as if we were beaten. The ice covering the rocks was just too thin to make reliable steps. It looked as if we might have to climb down the whole 1,000 ft. of the gully. Then Mackinnon took over the lead and forced a way on to the wall of the enclosing north buttress, and in a fine piece of route finding had us up.

“The best climb since Uja Tirche*,” we agreed, and one of the most difficult climbs we have done on any mountain range, with every character of suspense and difficulty in the greatest tradition of exploratory mountaineering. That is the quality of Scottish climbing.

* Uja Tirche, over 20,000 ft. in the Garhwal Himalaya was climbed by the present party, including W. H. Murray, in 1950. It took 18 hours, finishing in darkness.

Speaking of mountains, I must tell you of a book I have just read, The Ascent of Rum Doodle by W. E. Bowman. (Max Parrish 10/6). It is a book that takes “the mickey” out of mountaineers, yet does it so uproariously that no one—not even I—can take offence.

Rum Doodle, 40,000 ½ feet (approx.) is situated in the country of Yogistan, where the unit of currency is the bohee (worth ¾ d) and the taciturn natives smoke a villainous tobacco called stunk. Nothing will induce them to work longer than an eight-hour-day, except money.

It is the country of the Atrocious Snowman, but not until we stand on the pass of the Rankling La and confront the mighty peak of Rum Doodle do we meet the first purple passage. There, gilded by the setting sun is the mighty monster on which the expedition dare to set presumptuous foot.

It is one of those moments, the leader says, when a man is very close to himself. Then, delightful sense of the ridiculous, he adds, “we stood close to ourselves until sunset.”

This is a completely crazy narrative, of missing camps ; adventures in crevasses, of the leader’s preoccupation with the love-lives of the sahibs, and the haunting influence of Pong the expedition cook, the only member of the party not worth his weight in bohees.

I think it is Somerset Maugham who separates farce from comedy by saying that farce appeals to the collective bellies of an audience, whereas comedy appeals to their intelligence. By this reckoning Rum Doodle is a farce, but what a delightful farce it is.

A Remarkable Village

The time is approaching for hard thinking about holidays. May I suggest Gardenstown, 15 miles from Fraserburgh on the Moray Firth? Here is Scotland’s little bit of Devon – in great cliffs of red sandstone alive with sea birds, and curving bays in which are set fishing villages as colourful as any in the south.

All the villages on this rocky coast have spectacular settings; Crovie, sandwiched between the sea and the cliffs, too close to both for the comfort of the natives ; Pennan at the foot of another cliff but situated on a delightful bay within sight of the noblest headland of this superb coast, a village where fulmars fly among the roofs of the houses.

Apart from its beauty Gardenstown itself is one of the most remarkable fishing villages in Scotland. It is without a deep-sea harbour, yet its 1,250 of a population earn over £400,000 annually from the sea. Fishermen of this village must go 15 miles to put to sea. Locally they are known as Gamericks— Gamrie being the local name for this picturesque village which has somehow been overlooked by the holidaymaker. It is one of the most prosperous places in Scotland. The inn is good and there is plenty of accommodation in the village.

Dear Sir,

Will you permit me to point out an error in the March issue of ” Scots Magazine.” On page 489 “Mr William Thordburn rings Britain’s smallest bird.” The wren is not Britain’s smallest bird. The gold crest has that distinction.

May I take this opportunity of saying how much I enjoy this magazine. It goes to my cousins in Australia (Melbourne) when I have finished with it.

I am, yours sincerely,

(Miss) Margt. ) O. McWilliam.

St Konans, Kaglesham, Renfrewshire.

Tom Weir says ; “Miss McWilliam is quite right. What I should have said is that the common wren is the smallest bird ringed, since ornithologists regard it as bad practice to ring the gold crest.”

- Zoom-in for carousel. Scots Mag copyright.

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.