Tom Weir | Source of the Clyde

Tom Weir travels the River Clyde, from “God’s Treasurehouse” to Glasgow, and considers the different lives played out on its banks through the ages…

Crawford derives its name from the numerous crows which still nest in the trees around Lindsay Tower, also from the fact that there was a ford over the Clyde near this fortification which lies close to the road the Romans built called Watling Street.

What a pleasure it was to stroll along that ancient road and take in the peaceful scene after the stir of the A74 which gives me, literally, a pain in the neck, through constant glancing in the mirror to see what’s coming up behind, and watching the overtaking antics of the long vehicles thundering along at frightening speed.

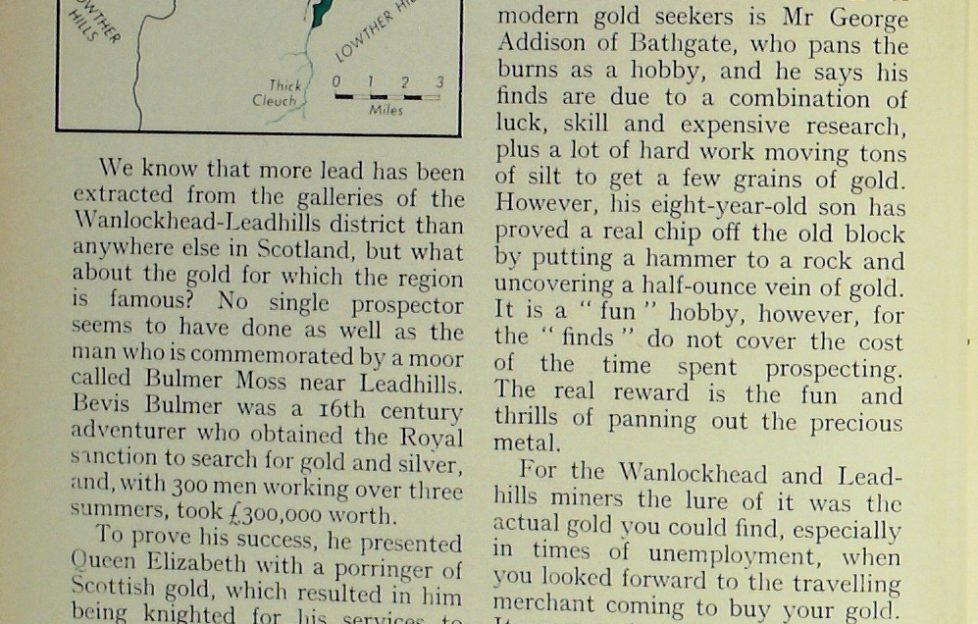

Watling Street at Crawford was an extension of the road that ran from Dover to York, with northern branches serving Hadrian’s Wall, and crossing over Beattock into the drainage of the Clyde en route to Old Kilpatrick, the north-western limit of the Roman Empire.

Considering the reputation of the Romans as great mineral seekers, it is surprising that in this region there is no record of them exploiting the Lowther Hills which have been called “God’s Treasurehouse” because of the enormous underground wealth taken from them in more recent times.

Early prospectors and modern gold-seekers

We know that more lead has been extracted from the galleries of the Wanlockhead-Leadhills district than anywhere else in Scotland, but what about the gold for which the region is famous? No single prospector seems to have done as well as the man who is commemorated by a moor called Bulmer Moss near Leadhills.

Bevis Bulmer was a 16th century adventurer who obtained the Royal sanction to search for gold and silver, and, with 300 men working over three summers, took £300,000 worth.

To prove his success, he presented Queen Elizabeth with a porringer of Scottish gold, which resulted in him being knighted for his services to the country. A bright green field and a couple of pine trees on the river still mark the place in Glengonnar where his house once stood below the hill which commemorates him. Above the door lintel was an inscription :

In Wanlock, Elvan and Glengonnar

I won my riches and my honour.

He frittered away his riches, however, and died in debt, owing £340.

George Bowes was another gold seeker who got the chance to try his luck in Wanlockhead in Queen Elizabeth’s time. He struck it rich, finding big nuggets, one of them nearly two pounds in weight, but he didn’t fully exploit the gold-bearing vein.

Swearing his men to secrecy, he closed down the working against his future return. He never did, because in Cumberland he was killed by falling down a mine shaft. Twentieth century prospectors are still hoping to discover his lode.

One of the most successful of modern gold seekers is Mr George Addison of Bathgate, who pans the burns as a hobby, and he says his finds are due to a combination of luck, skill and expensive research, plus a lot of hard work moving tons of silt to get a few grains of gold. However, his eight-year-old son has proved a real chip off the old block by putting a hammer to a rock and uncovering a half-ounce vein of gold. It is a “fun ” hobby, however, for the ” finds ” do not cover the cost of the time spent prospecting. The real reward is the fun and thrills of panning out the precious metal.

For the Wanlockhead and Leadhills miners, the lure of it was the actual gold you could find, especially in times of unemployment when you looked forward to the travelling merchant coming to buy your gold.

It was a custom, too, at one time, to help a bridegroom find gold enough to make a wedding ring from grains so small that they had to be picked up by tweezers. For encouragement it should be mentioned, however, that the biggest nugget found in the last 200 years was found in 1940, and it weighed 500.2 grains.

From miners’ cottages to holiday homes

With mining ended and no alternative industry forthcoming I expected to find some gloom and despondency about the future of these highest villages in Scotland. Not a bit of it. The motor car has made it possible to live here and work outside, in Lanark, or Hamilton – or even Livingston New Town.

Vacant homes are eagerly snatched up, and in summer more and more tourists drive off the A74 at Crawford and Elvanfoot to look at the village and enjoy the peace of the hills before crossing the Mennock Pass.

“The history of the village and the museum-trail is a great attraction. Thousands of visitors come every year now,” said Joe Scott of Wanlockhead.

The big demand now is for holiday homes, it seems, houses which in the first instance were built by the miners themselves and thatched with heather. Then about a hundred years ago, they were rebuilt and roofed with Welsh slate to be held rent-free by miners who had land for cultivation and kept milk cows. Leases were held by the landowner but the croft and house were held to be the property of the miner, who paid 1/- out of every £5 earned to help to support the poor.

I find it strange that Thomas Pennant dismissed these high villages as being dreary, without taking account of the social conditions which, for miners, were far ahead of their time in 1770. He does not even mention that the villagers paid for their own doctor, through contributions of 4/- a year from each miner. He might also have noted that crime was unknown, and this was at a time when life in Scotland was very difficult for ordinary folk arid beggars were everywhere.

The railway came to Leadhills in 1901, climbing up from Elvanfoot, and a year later reaching Wanlockhead. It closed in 1938, and the lady who gave me the information showed me two historic railway tickets, one bought on the first journey, and the other on the last.

The line’s course is now a smooth grassy track climbing gently from the Clyde at 1000 ft, to cross the Elvan Water, then taking to the flanks of the hill. I enjoyed a walk on it, especially crossing the big viaduct to a loud cackling of courting red grouse.

I liked what I had been told about the trains that operated on the line. Passengers were few, so the train acted like a taxi, picking you up at the wave of a hand, and setting you down where you wanted to get off. Thanks to the heavy weight of lead carried from the mines to Elvanfoot the wee branch line was said to be the best paying of the Caledonian Railway network. I wish I had taken my chance to travel on it, for I could have done.

When I was a youngster, the railways used to run cheap excursions to the source of the Clyde, to Elvanfoot. On arrival there, the excursionists would look at the hills just east of Beattock summit, where the Clydes Burn rises under Clyde Law.

To the source of the Clyde

They believed it to be the source, too, and so did I, having no less an authority than Neil Munro in his book The Clyde.

Naturally I couldn’t be satisfied until I had walked up there, past a Roman fort, to follow a wee burn of waterfalls narrowing as it went up between Pin Stane and Clyde Law to become the crystal pool of water, so small that ” … a hat would cover it.” The words are Neil Munro’s, and in his book he describes amusingly how he and his friends arrested its flow by corking it up.

He describes how they boarded the train for the return journey from Elvanfoot hiding their guilty faces in their newspapers. They were thinking of the dreadful consequences of their follv:

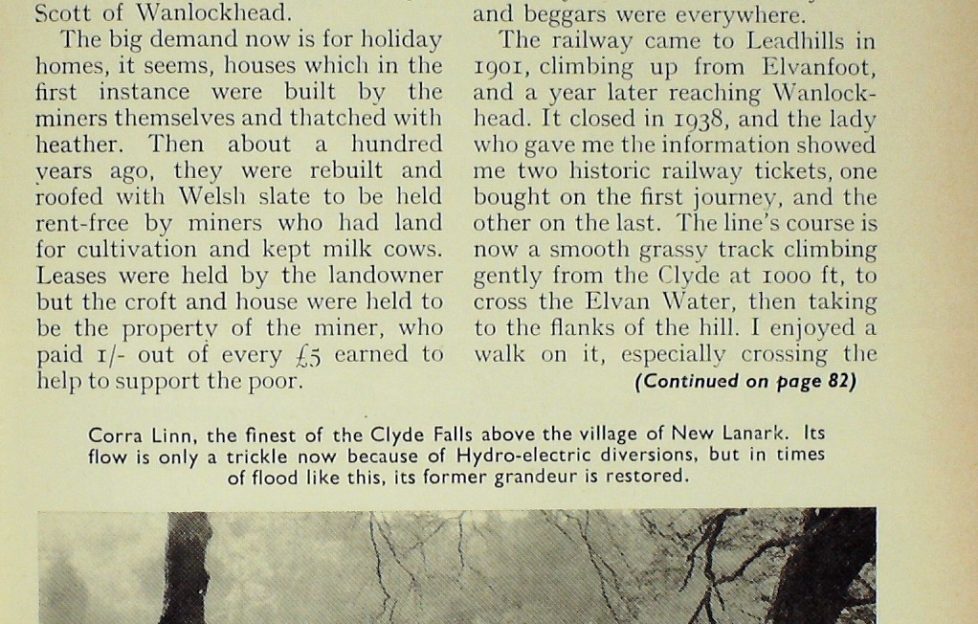

” Of the anglers suddenly finding themselves in the muddy bed of an arrested river ; of the first stillness of innumerable centuries coming upon Corra Linn and Bonnington. where erst the cataract roared ; of Bothwell’s ruin aghast over an empty, arid chasm ; of Glasgow horrified to find her ships keeled over in the fetid ooze, her proud commercial enterprise eminence destroyed mysteriously in an hour.”

Yes, a flight of amusing fancy, dated now because Glasgow’s eminence has gone, and Clyde water goes through a pipe and not over Corra Linn.

That is an academic point, though, for the spring of clear water which Munro and his friends corked is not the source of the Clyde but of the Evan Water which flows into the Annan, as I discovered when I revisited the place and saw that this burn flows on the wrong side of Beattock, making a falsehood of the ancient rhyme :

Annan, Tweed and Clyde

Rise aa oot o ae hillside.

To be fair to Neil Munro, he tells the reader why he chose to accept the spring on Clyde Law as the source—because it is nearest to Glasgow and most accessible of claimants for the title.

“The decision must be arbitrary,” he says. What he should have added is that the railway company were the main promoters of the wrong burn as source because it was a way of attracting excursionists from Glasgow to see where their great river rose in the hills.

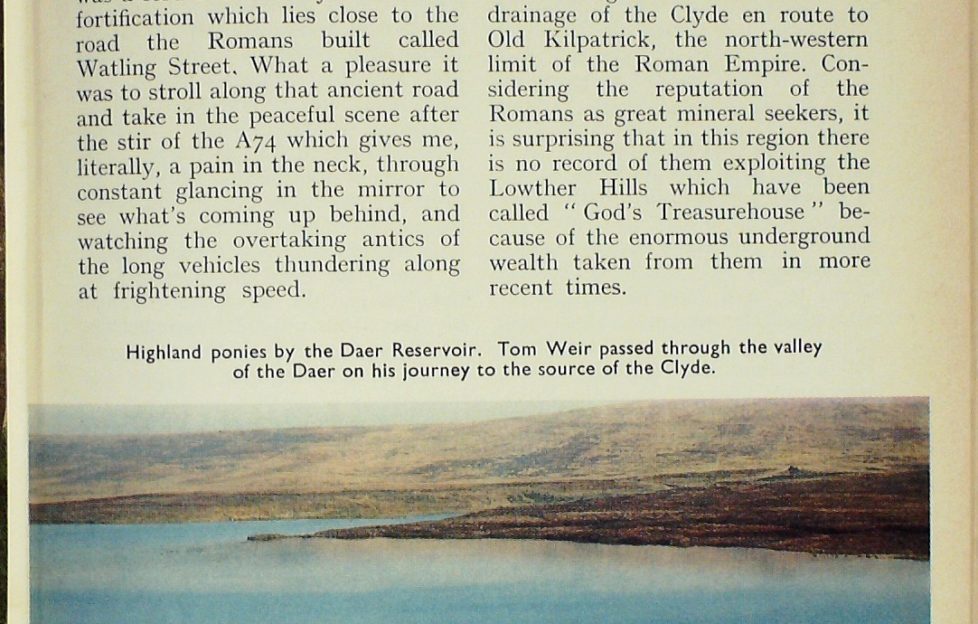

The source of the Clyde is, in fact, nine miles from Elvanfoot and in another valley, the valley of the Daer, whose upper waters are now gathered in a big reservoir. To get to the source I drove off the A74 south of Crawford and followed the A702 past Elvanfoot, branching off left in three miles on the road marked “Daer Reservoir.” Now I was in a fine little glen, climbing up past wee farms and forestry plantations, with a right fork taking me out level with the big sheet of water impounded by the dam.

Through lonely country

The road went on and so did I, past a herd of Highland ponies beyond which the tarred road became a rough gravel track, then broken by erosion channels. Eventually it reached Daerhead, beyond which I walked by Thick Cleuch to hop across the true source of the Clyde in the golden light of a perfect afternoon.

Lonely country, of butts on the heather for shooting grouse and bare dodds grazing sheep.

All I had to do now was motor back, and this time take the wee road to the other side of the dam to watch the water slurping from the reservoir into the viaducts to go through the big concrete treatment buildings below, while the eye ranged west to the ridges of the Lowthers, softened by haze and looking mighty high above the thin streamlet of the Clyde.

It is probably true to say that with the building of the Daer Dam in 1956 the source of the Clyde can be considered to be the reservoir, which sends its water to Lanarkshire. At the time of its building it also gave much-needed employment to the unemployed miners of Leadhills and Wanlockhead.

The word Clyde comes from the Welsh language, Clivyd, which means strong. From where I had been that afternoon to where the river reaches the sea at Dumbarton is a distance of 106 miles, and vast changes have overtaken bits of it in my lifetime.

At Bothwell there is a lake and a new-style country park. Hamilton Palace has gone. New tower blocks have risen, and there is such a complex of fly-overs and pass-unders that the Hamilton folk have given it the name of “The snake pit.” Look, too, at the once-busy dockland of the Broomielaw, the shipyards that have closed clown, and the new shape of Glasgow, built for motor cars rather than people.

Neil Munro would certainly be surprised were he to return today, not least because you can’t get a train to Abington or Crawford now because there are no railway stations.

Yes, the trains are there, but they are all-electric inter-city trains, which go tearing by. Local folk use the bus nowadays, for there is no railway station nearer than Lanark in this part of the world now. Who could have foreseen when the railway came here in 1848 that its trains would be moving so fast between Glasgow and London that they would have no time to stop at places on the way ?

Thomas Telford, son of an Eskdale shepherd, died only twelve years before the railway was built to Carlisle, but he it was who engineered the old A74, speeding the mail coaches and cutting drastically the time needed to travel between Scotland and England. West of the Lowthers is a memorial to another lad of these parts called John Louden Macadam, who lived at the same lime as Telford, and who transformed rough roads to smooth with the help of his tar kilns.

A Little Switzerland

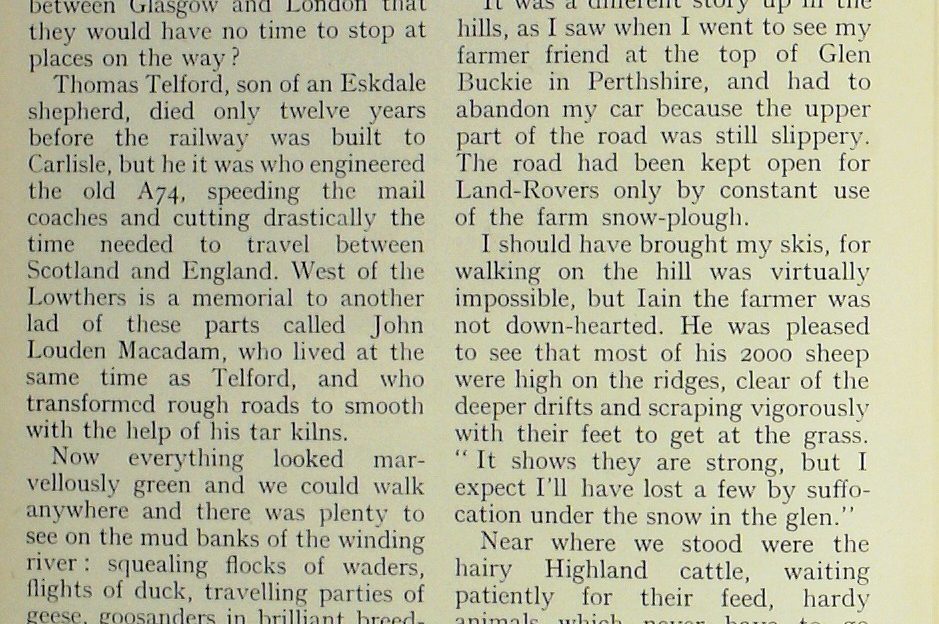

Now everything looked marvellously green and we could walk anywhere and there was plenty to see on the mud banks of the winding river: squealing flocks of waders, flights of duck, travelling parties of geese, goosanders in brilliant breeding plumage, but the best sight for me was a greenshank, rising with sharp triple call, showing grey wings and white back as it flashed swiftly upriver—one that had chosen to winter here instead of migrate.

Following the big blizzard, I’ve been having some good excursions round the local hills on skis, enjoying the long-lying, crisp snow and visions of Highland peaks as white as I can ever remember them. Loch Lomond- side has indeed been a little Switzerland, with days of sunshine and the limpid loch reflecting warm tints of shore and islands as well as the alpine heights.

Best of all has been the tremendous inrush of birds, possibly due to the freezing conditions elsewhere, grey geese by the thousand, whooper swans by the dozen, wild duck galore, big flocks of siskins, passages of pipits and goldfinches, and a twittering of snow buntings in a field above the house.

It was a different story up in the hills, as I saw when I went to see my farmer friend at the top of Glen Buckie in Perthshire, and had to abandon my car because the upper part of the road was still slippery. The road had been kept open for Land-Rovers only by constant use of the farm snowplough.

I should have brought my skis, for walking on the hill was virtually impossible, but lain the farmer was not down-hearted. He was pleased to see that most of his 2000 sheep were high on the ridges, clear of the deeper drifts and scraping vigorously with their feet to get at the grass. “It shows they are strong, but I expect I’ll have lost a few by suffocation under the snow in the glen.”

Near where we stood were the hairy Highland cattle, waiting patiently for their feed, hardy animals which never have to go inside except maybe when they have vulnerable calves as now. We went to look at one born only a few hours before, still shivering and with a matted coat. Upon the ridge behind the house, though, Highland ponies were rolling in the deep snow, kicking their legs with enjoyment.

It was raining heavily as we left the farm, and Iain hoped it would continue and clear away the snow. It didn’t. Another blizzard was on its way.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here for Tom’s online archives.