Tom Weir | A Spectacular Climb, A Changing Glen & A Climber Extraordinary

Tom Weir had just turned 62 when he wrote his monthly column for our January 1976 issue – and did the piece see him winding down with slippers by the fire, and more subdued ambles?

Did it heck. He was too busy scaling the North Buttress of Buachaille.

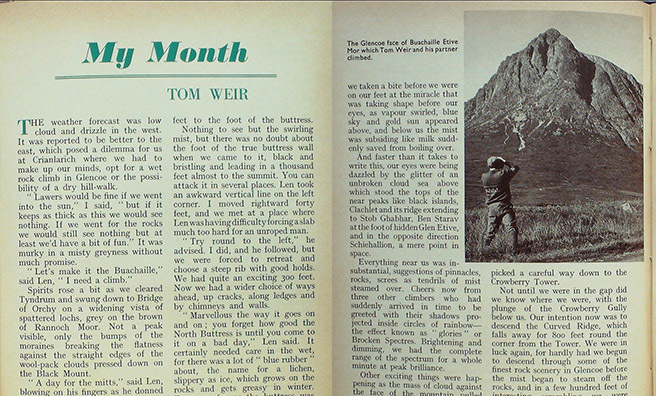

THE weather forecast was low cloud and drizzle in the west. It was reported to be better to the east, which posed a dilemma for us at Crianlarich where we had to make up our minds, opt for a wet rock climb in Glencoe or the possibility of a dry hill-walk.

“Lawers would be fine if we went into the sun,” I said, “but if it keeps as thick as this we would see nothing. If we went for the rocks we would still see nothing but at least we’d have a bit of fun.”

It was murky in a misty greyness without much promise.

“Let’s make it the Buachaille,” said Len, ” I need a climb.”

Spirits rose a bit as we cleared Tyndrum and swung down to Bridge of Orchy on a widening vista of spattered lochs, grey on the brown of Rannoch Moor. Not a peak visible, only the bumps of the moraines breaking the flatness against the straight edges of the wool-pack clouds pressed down on the Black Mount.

“A day for the mitts,” said Len, blowing on his fingers as he donned his boots, while I held up the rope inquiringly. He shook his head. “Too wet and cold for anything difficult. How about the North Buttress to get the blood and the hands moving?”

It would have been my own sporting choice, so off we went, lightly laden, hardly noticing the upward traverse to the foot of Great Gully, where the mountain suddenly rears up and you can begin scrambling on steep heather and rock for the few hundred feet to the foot of the buttress.

Nothing to see but the swirling mist, but there was no doubt about the foot of the true buttress wall when we came to it, black and bristling and leading in a thousand feet almost to the summit. You can attack it in several places. Len took an awkward vertical line on the left corner. I moved rightward forty feet, and we met at a place where Len was having difficulty forcing a slab much too hard for an unroped man.

“Try round to the left,” he advised. I did, and he followed, but we were forced to retreat and choose a steep rib with good holds. We had quite an exciting 300 feet. Now we had a wider choice of ways ahead, up cracks, along ledges and by chimneys and walls.

“Marvellous the way it goes on and on ; you forget how good the North Buttress is until you come to it on a bad day,” Len said. It certainly needed care in the wet, for there was a lot of “blue rubber” about, the name for a lichen, slippery as ice, which grows on the rocks and gets greasy in winter. Too soon for us the buttress was tapering off to the summit rocks, and ahead of us loomed the cairn.

“I wonder how many times we’ve sat here,” said Len as I got out the piece and handed him a tin of sardines to open. But hardly had we taken a bite before we were on our feet at the miracle that was taking shape before our eyes, as vapour swirled, blue sky and gold sun appeared above, and below us the mist was subsiding like milk suddenly saved from boiling over.

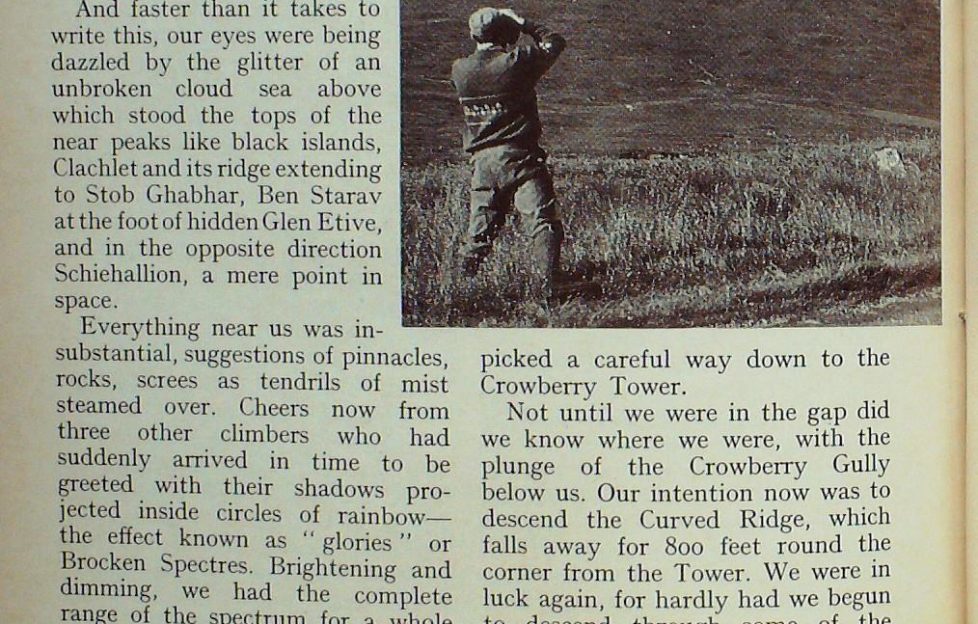

And faster than it takes to write this, our eyes were being dazzled by the glitter of an unbroken cloud sea above which stood the tops of the near peaks like black islands, Clachlet and its ridge extending to Stob Ghabhar, Ben Starav at the foot of hidden Glen Etive, and in the opposite direction Schiehallion, a mere point in space.

Everything near us was insubstantial, suggestions of pinnacles, rocks, screes as tendrils of mist steamed over. Cheers now from three other climbers who had suddenly arrived in time to be greeted with their shadows projected inside circles of rainbow— the effect known as “glories ” or Brocken Spectres. Brightening and dimming, we had the complete range of the spectrum for a whole minute at peak brilliance.

The scale could have been Himalayan

Other exciting things were happening as the mass of cloud against the face of the mountain pulled away, giving us a glimpse down 2000 feet of pink rocks and screes into a bottomless hole where the mist swirled in a black cauldron. The scale could have been Himalayan.

“I don’t know when I’ve been more thrilled by anything,” Len was saying, as we were enveloped again so thickly that we could see no more than a yard or two as we picked a careful way down to the Crowberry Tower.

Not until we were in the gap did we know where we were, with the plunge of the Crowberry Gully below us. Our intention now was to descend the Curved Ridge, which falls away for 800 feet round the corner from the Tower. We were in luck again, for hardly had we begun to descend through some of the finest rock scenery in Glencoe before the mist began to steam off the locks, and in a few hundred feet of interesting scrambling we were enjoying the whole glory of the mountain, as one buttress after another solidified, while below us opened the quiet bronze of the glen, warm with sunset light.

It was hard to keep moving. We wanted to stand still and watch the rapid changes behind and in front of us, as streamers of cloud, tinted with the pink of sunset, drifted across the summit. Down the glen the very top of Stob Coire nan Lochan stood above a trough of cloud still lingering below the Three Sisters. Sorrowfully we turned away over a Rannoch Moor winding between lochs luminous with the reflections of sky and dark mountains.

“Frost tomorrow for sure,” I said to Len as I dropped him off at Bridge of Allan. Even so, I did not expect such a sparkler, as I stepped outside next morning into a world of rime aglow with the sunrise, and you couldn’t walk without leaving a footprint as in snow.

A Changing Glen

Glorious to go down to Loch Lomond a mile from the house in frost crystals sparkling with red and blue fire, though already they were turning to globules of water in the brilliant sun.

I was in luck. No one had been there to disturb the birds on the glass-calm water, and from the cover of the oaks I could look and listen to the great congregation, the rattle-wings of flighting golden-eye, the sharp little squeals of teal, the quarking of mallard, the honking of a string of whoopers, sailing with necks erect, the talking of the geese out of sight round the corner.

Then in front of me I picked out in my glass a neat diving bird, sparkling white on chest and neck with a curious straight line of black across the white face, extending to the crown. With its back to me, it looked a dark, featureless bird of elegant shape. Face on, it seemed as white as a gull, with a black bill and black crown : a Slavonian grebe, only the third recorded on Loch Lomond.

My next outing was to Glen Lyon, in torrential rain, which brought down the burns in as fine spate as I have ever seen, especially the one above the so-called Roman Bridge. Falling in a big ribbon of spurting white, it looked like a snow gully in the dark face. The ravines of the Pass of Lyon were savage that day, and I took great care as I scrambled on the crags above the torrent, where the big potholes had chiselled the rocks into narrow aretes. One outline at the Black Bridge has the profile of a noble Roman face.

At MacGregor’s Leap I paused to consider where I would jump if I had to leap the river to avoid death —as he did, bloodhounds on his heels and avenging Campbells out to knife him. I don’t think he had much choice, for to leap the Lyon anywhere here you need all the height you can get, and the miracle is that he managed to land on the broken rocks of the other side without breaking his legs. I feel sure I could make the leap, but I am equally certain that I should probably die like the travelling showman who tried it many years ago but paid with his life on landing.

I decided to consult someone who knows the glen well—Mrs Alexandra Walker—in the hope she might know about the leap. She told me she did not know the precise spot, but she was happy to come up the glen with me and talk to me about her famous shoemaker father and show me her old home at Woodend. The workshop is still there, with the rusty last outside, where Alexander Stewart made shoes by day and spent his evenings writing and gathering information for his remarkable book, A Highland Parish—the most readable and best book of its kind built around a single glen.

It was fine to have a spry 79-year-old for company who could illuminate the past from stories handed down by her father and from her own life experience.

“Yes,” she said, “he remembered the crofters taking their cattle to the summer shielings, and I remember seeing the drovers taking the sheep and cattle to walk them to the market. In my young day Glen Lyon was a lively place, there were so many living in it, crofting, working on the farms and on the estates. There was always a lot of fun, for people made their own entertainment. Any house was open to you, especially the farmhouses.

“They came to play cards, have a tune on the melodeon or the fiddle. They told stories, or gathered round a travelling packman to hear the news of the outside world. Everybody was welcome at the shoemaker’s shop, and nobody went away without a bowl of soup or tea and a piece if they needed it. My father didn’t like shoemaking, but it was a living, because everybody bought things locally in these days, before readymade articles banished the local tailors and the weavers and millers.

“The farms and the houses needed a lot of labour, and people worked their own crofts. We had cows and sheep and hens. It was a busy life, but my father made time to write, for The Oban Times, and working on his book. He saw the changes brought by the deer forest system.”

I remembered a poem Alexander Stewart wrote about Glen Lyon :

O shame that the native mountaineer must give way to the grouse and the antlered deer,

On his native heath he had prior claim to the southern sportsman in search of game.

“The people didn’t get the chance to own the farms they had worked,” she went on. “But Iain Slatich was lucky. His mother got the offer of their place at a price she could afford. You should talk to him.”

Iain, lean and in the prime of life, enjoys his farming, which is sheep on the hill, cattle in the glen, and some arable. But he has his problems.

“It gets more and more difficult every year. You can’t get men. They say it was after the First World War that people lost the notion of living in the glens. They had seen the world outside and wanted into it. But even if I could get a man now, I don’t know if I could afford him. Everything you buy gets dearer. We’re fifty miles from the market, so on top of everything there are transport costs, and the profit margin gets less.

“Glen Lyon is a beautiful place to live and work, no doubt about that, but the hills go up to nearly 4000 feet on the south side, and to 3400 feet on the north side, so you have to put up with a short growing season and a lot of bad weather. To make a living today you have to work very hard for what you get. I don’t see my boy following on.”

There was food for reflection in what I had heard. In Glen Lyon I could see a microcosm of Highland history. The longest glen in Scotland, it held 700 in Alexander Stewart’s time. Today it holds under 50; houses that come up for sale are bought by people looking for holiday homes or for retirement. Prices are high. Cottages which once held shepherds are now under the water of hydro-electric reservoirs, and even Forestry Commission workers travel into the glen from the outside. In living terms the glen is dead, and likely to remain so as long as greater opportunities for a higher standard of life are to be found elsewhere. Even the one shop at Bridge of Balgie is difficult for the owner, because the glen folk go away in their cars to buy their goods.

A Climber Extraordinaire

Back home again, I was getting down to work when a voice came on the telephone, strongly Lancashire and alive with excitement. I won’t try to put it in dialect.

“Tom, it’s Stan Bradshaw. I’ve been at the Munros on my own for a week. It’s been marvellous. Yesterday I was above the clouds, at 3000 feet in the sun with nothing but mist all round. I’ve done nineteen Munro tops, and I want to make it 20. How about joining me for Ben Challum tomorrow? It’s my last day. Can you make it?”

Before such enthusiasm what can you say? Especially when the man is Stan, whom I met for the first time on the Cuillin ridge a year ago and wrote about in “My Month” for September 1974. On that occasion I had watched Stan and his friend Frank Milner pick their way down Bidein Druim nan Ramh on their way to finishing the whole Cuillin Ridge in a single day. But alas, they had failed on the Bhasteir Tooth, and thirty-one hours from setting out they were back at their Loch Coruisk base.

By any standard that was a good attempt. I drove north to meet him, because he went back to the Cuillin last June and I wanted to hear the story of his triumph. Stan is 63, and wonders if he is the oldest man to have done it. Small, bald-headed, light and wiry, he had the coffee boiling when I arrived on him at breakfast-time for Ben Challum. During our climb he told me all about the most wonderful day of his life, beginning at 3.30 a.m. in Glen Brittle and finishing at Sligachan at 11 p.m.

“It was perfect, except for taking a third man along who slowed up Frank and me. But he gave up halfway, and we got moving then. We had a cache of food planted at the Inaccessible Pinnacle, and once we got it we felt sure nothing could stop us. We were tired when we got to the Bhasteir Tooth, and once again we couldn’t find the route, although we had made a reconnaissance in advance. We wasted a bit of time and energy, but once we were up we could relax, for we knew that nothing could stop us getting to SguiT nan Gillean. It was beautiful! Everything about was grand—the colours, the sea and, swinging away from us, the marvellous ridge and the corries we had traversed.”

Telling the tale to me as we climbed, I noticed that he never seemed to pause for breath as the top of Ben Challum came nearer and nearer. I had never thought of it as an exciting hill, but Stan grew excited as the corrie opened up and a whirling flock of thirty ptarmigan crossed in front of us, white as doves. The cause of the alarm was immediately apparent, when over the ridge came an eagle, its broad wings beating as it crossed our flank.

Strangely, there was a flock of twites up here, too, despite the frozen ground and the cold wind that made us put up our anorak hoods. It was fine to get into the lee of the cairn and have a cup of hot soup and a jam butty while watching the moving black clouds obliterate peaks, or pass and reveal winking eyes of lochans, one of them pin-pointing our route of descent by the south corrie.

Nice to jog down the rocky corrie sweeping down to Lochan Dubh and listen to Stan telling me of his lifestyle as a tripe manufacturer, cross-country runner, fell-racer and hill-walker. He told me how the building up of his business hadn’t left him any time for climbing until he was 40, but that he had always been a harrier.

“I do four miles every day before breakfast in any weather. And I run six miles every evening after work, before tea. I’ll run six miles tonight, and I’ve done so every day since I’ve been up here. After coming back from the hill I have a cup of tea, then go out for my run and come back to a big meal I eat a lot.”

In fact, I did not know what a remarkable individual Stan was until I talked to his Cuillin companion, Frank Milner. Stan, it seems, is a legend in his own country, having at the age of 48 knocked a little off the time taken by Bob Graham to round 42 Lakeland summits in 24 hours, a record which stood for 28 years until Alan Heaten did the second round. Stan was the third man to do it.

He refuses to grow up or grow old

Another of his feats was a winter run of 120 miles and 20,000 feet of up and down work to link the two highest pubs in England, Tan Hill in Yorkshire and the Cat and Fiddle in Cheshire. Doing this with a couple of friends, they took only 51 hours and 49 minutes, without sleep, in rain, snow, mist, hail, thunder and lightning. They set out on Boxing Day. Stan has also done all the summits over 2500 feet in Lakeland in a continuous walk, 105 miles of ascent and 77 summits, all between Saturday morning and Tuesday morning.

Ah, well, it is encouraging to meet a driving force like Stan, who doesn’t know where to stop and who refuses to grow up or grow old. I went to the funeral of another man of that kind a few weeks ago, Dr J. H. B. Bell, with whom I had the pleasure of climbing in 1968 when he was in his seventies, yet he was doing the Munros for the second time and planning to go to the Alps that summer.

Bell was an Auchtermuchty man, chemist, scholar and editor of The Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal. He was one of the big names in British climbing between the wars. Small and lightly built, like Stan Bradshaw, Bell at the age of around fifty pioneered some of the hardest climbs ever done on Ben Nevis. The Orion routes on the North-East Buttress will be amongst the finest of the Scottish classic routes for situation and difficulty.

Now he is dead, a great character gone, while Stan Bradshaw is off to the Canaries to climb a volcano in Tenerife. The great thing about life is to live it to the full when you have the chance. It’s the best recipe for happiness.

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, and a new column is published online every Friday.

More from 1975

More from 1976

More instalments every Friday