Tom Weir | Isles of Inspiration

In a trip to the Orkney Isles, Tom Weir clambers around the Old Man of Hoy, and visits a very special resident on North Ronaldsay

I have a confession to make. Until recently I had never visited the Old Man of Hoy, though I must admit that I felt we were very old friends, for in the spectacular film of its ascent by three different routes I was the stand-by commentator for the BBC from their Glasgow studio.

Now here I was in Orkney, on the pier at Stromness, in the rain, waiting for the morning boat that leaves at 8.30 a.m. every weekday, returning at 4.30 p.m.

Of Hoy just across the water, nothing could be seen, and I would have put off the visit until another day if the Met. Office at Kirkwall hadn’t told me there was no hope of a clear-up for some time.

An Illusion of Sunshine

So off we went to Linksness pier on Hoy under the highest hills of Orkney, guessed at rather than seen that morning. We took the hill road west until it becomes a path bending south past the Sandy Loch where great skuas wheeled overhead and fulmar petrels had nest sites on wee rock outcrops just round the corner.

Once off the road and on a true hill-pass, spirits rose. My wife averred that the rain was refreshing. It was also going off, and there was even an illusion of sunshine as we came in sight of green Rackwick and the sandy curve of its bay set between pillars of pink cliff, the houses perched here and there giving it a feeling of life.

Alas, Rackwick is a ghost village of ruins and memories of times past, as talented local artist, lan Machines of Stromness explained when he invited us into his holiday cottage for coffee.

“The school, which is now a hostel for outdoor folk, closed over 40 years ago. It’s the old story, the young folk left to better themselves, and the old folks remaining died one by one. At last there were only two wee boys in the village. They used to play with my youngster.

“One morning they drowned playing with a raft in the burn. It was the end, but the Highlands and Islands Development Board is helping Jack Rendell to restore ‘The Glen’ and make a go of crofting the place, so maybe the idea will spread. It’s such a beautiful place.”

Certainly Ian finds inspiration in the setting as does the composer Peter Maxwell-Davies who needs complete peace to write his highly acclaimed music.

Perched high above the bay and reached only by a steep footpath, his simple cottage has the finest outlook in all Orkney. I climbed past it on my way to the Old Man of Hoy, interrupting him only for a moment to say hello, for there was a lot on his mind and he had much to do.

The easiest way to the famous pinnacle is from the school over the flank of Moor Fea among the skuas and the greater blackbacked gulls. Although not marked on the map there is a good footpath, as well as a notice warning climbers that they go at their own risk for there is no rescue service on Hoy.

We were in luck when suddenly in front of us the Old Man stuck his head out of the mist, lower parts invisible until we got to the edge of the cliff and we saw his great skeleton.

The First Assent

The story of its first ascent was brilliantly told by the late Tom Patey in the December 1966 issue of this magazine. Patey wrote: “As you climb higher there is a unique sense of physical detachment and height ceases to have any morbid significance. We were higher than St Paul’s Cathedral, and by the time we reached the top we would be level with the new Post Office tower, London’s highest building.”

Tom had declared after the feat that there wouldn’t be a next time. But of course there was, or I would not have been in the television studio watching the antics of Dougal Haston, Joe Brown, Peter Crew, MacNaught Davis, Tom Patey and the other stars.

How has the Old Man fared since he was first conquered 13 years ago? The answer is that it is now a commonplace climb and done by over a score of parties every summer. I spoke to a quartette of English youngsters who had just done it. I asked if they had found it hard.

“Not too hard,” they opined. “But it took us quite a time, even although all the ironmongery was in place.”

While we stood up on the airy headland, looking down on the fulmars on their ledges, the mist swirled clear of St John’s Head and a gleam of sun warmed the great Orkney cliff a rich red. Plunging in great overhangs and verticalities for 1100 feet it too has been climbed, but it took five days, the climbers using mechanical aids and sleeping out on the face.

To honour the lifeboatmen of Hoy who died in a wild storm they have named their climb “The Longhope Route.”

The cliffs and moors of Hoy could hardly have been in more contrast to the scenery of the island we had just come from, North Ronaldsay, most northerly of all the Orkneys looking to the Fair Isle and the Shetland Mainland. Our plan was that we should go there on the once-weekly boat.

Fate conspired against us.

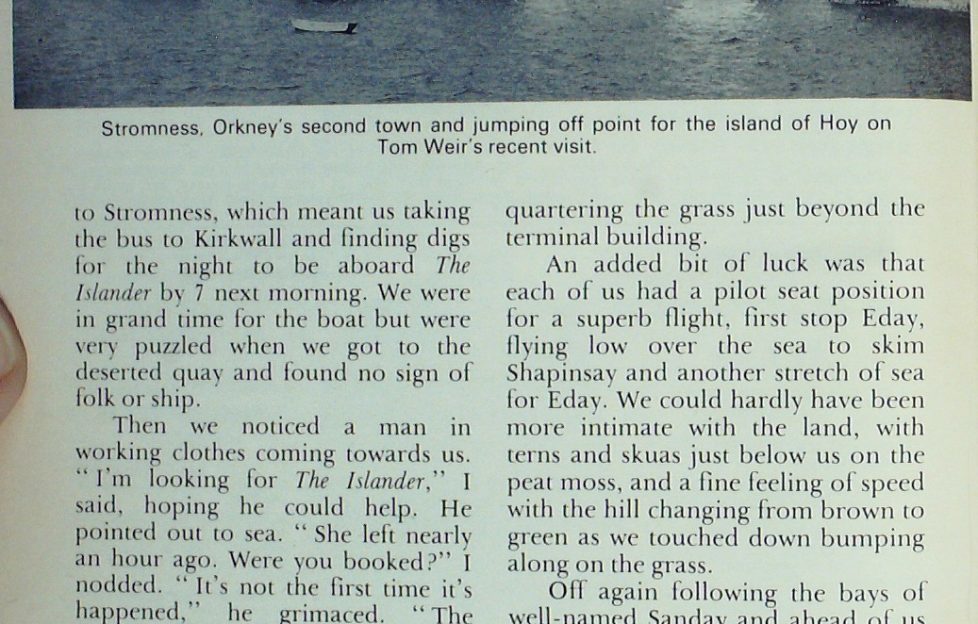

First, the car broke down on the road to Skara Brae and had to be towed back to Stromness, which meant us taking the bus to Kirkwall and finding digs for the night to be aboard The Islander by 7 next morning. We were in grand time for the boat but were very puzzled when we got to the deserted quay and found no sign of folk or ship.

Then we noticed a man in working clothes coming towards us.

“I’m looking for The Islander,” I said, hoping he could help. He pointed out to sea.

“She left nearly an hour ago. Were you booked?” I nodded. “It’s not the first time it’s happened.” he grimaced. “The sailing time was changed late yesterday. I said that somebody would be sure to be inconvenienced. You didn’t give them a telephone number?”

We couldn’t, because we didn’t have one.

What now? The harbour official said he would drive us to the airport to be there at 8 a.m. in the hope of getting a Loganair inter-island plane. Placed on stand-by we were in luck, we each got a seat, though on different planes. Waiting to go I had been watching a short-eared owl quartering the grass just beyond the terminal building.

An added bit of luck was that each of us had a pilot seat position for a superb flight. First stop Eday, flying low over the sea to skim Shapinsay and another stretch of sea for Eday. We could hardly have been more intimate with the land, with terns and skuas just below us on the peat moss, and a fine feeling of speed with the hill changing from brown to green as we touched down bumping along on the grass.

Off again following the bays of well-named Sanday and ahead of us was the flat line of North Ronaldsay, blue in the distance but suddenly rich green and yellow with flowers as we pitched down and dismounted into fragrant air. I am all for airstrips without tarmac, and the informality of collecting your own luggage and walking off.

An Undoubted Winner

The story of why I had sought out this particular island begins in a Perthshire post-bus. I had contacted David Dove of the Scottish Postal Board for information about the mail-bus routes serving the glens, and as a result he had asked me if I would act as one of the judges of an essay writing competition open to school children.

The essay had to be in the form of a letter, and the subject was “Places to Visit.”

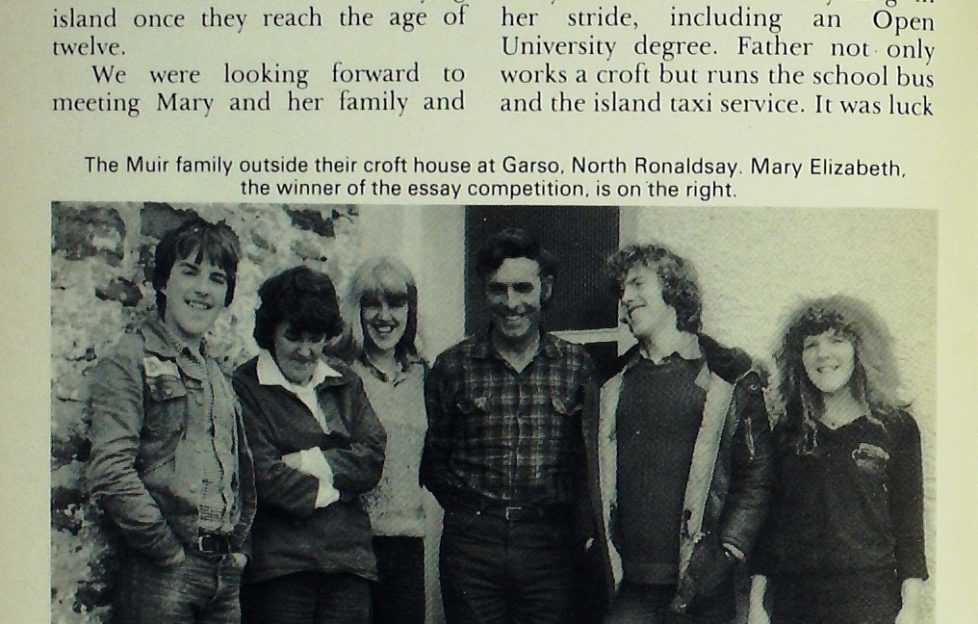

There was no doubt about the winner in the Scottish senior section. The £50 prize went to Mary Elizabeth Muir for the description of her home in North Ronaldsay, and the attractions of Mainland Orkney where she attends Kirkwall Grammar School, as do other children of this outlying island once they reach the age of twelve.

We were looking forward to meeting Mary and her family and getting a wee conducted tour of the little island which she had described as being “three miles long and one and a half miles wide.” Her father was down to meet the plane and soon whisked us to the house of Garso at the north end a good four hours before I could have reached it by boat.

How nice to arrive in a home from home and be made instant members of a family, sharing the normal way of life on the croft. Mary’s mother takes everything in her stride, including an Open University degree.

Father not only works a croft but runs the school bus and the island taxi service. It was luck for us to have the two boys and two girls at home before the summer holidays ended and took them to Kirkwall.

Island Life

First though a walk with prize winner Mary to the north point of the island, an exhilarating daunder to the bouldery shore through green fields and amongst shingly lochans alive with flying birds, golden plover and peewits by the score. And the terns in the hundred, rock doves in the fields and shelduck on the water.

We walked along the famous wall which entirely surrounds the island and is something of a mystery. High and thick its length has been stated at 15 miles following the windings of the shore. It is maintained by the crofters to keep out the unique breed of sheep which feed on seaweed and are renowned for the quality of their mutton.

I thought them vaguely reminiscent of the goat-like St Kilda sheep, in their agility and dun colour. Ewes are brought to grass inside the wall in lambing time. The earmarks denoting the owners are identical to the type used in the Faroes and Iceland. Mary says that the sheep are under the auspices of the sheep court, elected by men of the island, and that is one of the oldest courts in the world. As to the age of the perimeter wall girding the island, a recent book on the Orkneys states that it was built last century.

As we watched the sheep eat the seaweed, picking up mouthfuls ol juicy ribbon-like morsels, a flock of migrant knots landed beside some turnstones, only a small indication of how good this island is for bird migration, akin to Fair Isle.

In the old days there was a fishing station at Noust and there are still plenty signs of kelp burning Ironi so long ago. I was to hear about this later. Meantime we were interested in the seals basking along the shore, wailing to each other but unwilling to forsake the warmth of the sun for the cold water.

The Burrian Cross

Just beyond was the Burrian Broch whose outer face has been incorporated into the wall and the entrance blocked up. Excavations around here have yielded a hut settlement and finds of bone combs and needles, spinning whorls, scrapers and flints. Mary describes in her letter the most exciting thing which has been found, he shoulder blade of an ox with Pictish symbols and a Christian cross incised on it. This Burrian Cross and Pictish symbols are now used in Orkney Silver craft jewellery.

Virtually the whole of North Ronaldsay is farmed to rear beef, with the emphasis on silage, hay pasture, a little barley, turnips and some vegetables. Most crofts are small, but mechanisation is widespread.

Willie Thomson, of Neven near the Muirs’ house, spoke to me of the changes he had seen in his 7 ½ years, remembering when the population was three times what it is now and cash in your pocket was relatively unimportant. You lived on what you could grow and the fish you could catch.

“I remember watching boats going to the Fair Isle fishing grounds, sail after sail. I was told not to count them going out, it was bad luck, but to wait for them coming back. There were sixty pupils in the school when I was a boy. Now it’s only live, four girls and one boy.

“Stronsay was a great fishing station in my day. The boats were 40 to 60 ft. with a lugsail, and we went away for a week at a time. There was a crew of five. It was after the 1914-18 War the island started to go down. Of course there had always been a lot of emigration to Canada and Edinburgh. In Leith there are as many North Ronaldsay men as in North Ronaldsay itself.”

“I’d rather be here than in any city.”

“Look at Kirkwall, people hurry past, never giving you a look. The hard pavements are sore on your feet. The world is full of crime today. You would nearly need a lock on your pockets. Here on North Ronaldsay I never knew anybody who locked a door. There is no such thing as crime, thanks be to Providence.”

Willie, retired now and in not too good health, has a hobby which passes the time, painting schooners and sailing ships in full rig on the glass floats which fishermen use on their nets—real works of art produced on a curved surface. He also paints conventional pictures of them.

He remembers with pleasure the days when he was a crofter-fisherman, when the island was well populated and everyone worked at the same task, the kelp gathering, the ploughing with horse and oxen, hay-making, harvesting, sharing a communal life.

“I think we were happier,” he opines. “Now it’s all machines and money and hardly anybody keeps a milking cow. In the old days there was a lot of fun, and the quality of your work was noticed. You always wanted to be the best at a job. Without the variety of crops the island is not so bonnie as it was. It was lovely in the harvest time with the different colours.”

Yet it is unlikely that North Ronaldsay will ever be a Rackwick in terms of decay. The trend is that farms will get bigger, crofts will be enlarged as population declines, and fewer people will make a better but a duller living.

Things are fairly healthy at present. Of the 120 or so people who live on North Ronaldsay about 40 per cent are old age pensioners, but there are over a dozen under five years old and about 14 families between 40 and 60, plus four couples between 20 and 40.

In terms of children, a dozen go to Kirkwall Academy, as well as the five in the village primary school. This does not include lighthouse keepers, the resident doctor and the school-teacher, who is from England.

I’d like Mary Elizabeth Muir to have the last word.

She ends: ” When I think of home in summer, I think of the smell of clover, wildflowers and warm hay. In winter I think of the glittering constellations of Orion, the Great Bear, the pale iridescent streamers of the Northern Lights. The moon glimmering on the dark waters of the loch where the wintering swans are sleeping. The sound of the sea, in all its moods, is never far from my ears…”

Publishing this article 37 years after it was written, I wonder where that little girl is now and whether she still calls North Ronaldsay home. We’re heading up there in June for a forthcoming feature – if Mary Elizabeth Muir happens to be reading this – get in touch!

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.