Tom Weir | Stravaiging The Tops

Stravaig is a great Scots word. You can occasionally hear landowners use it negatively to refer to the “stravaigers” who trample through their fields, but for most – and certainly for Tom Weir – it is used in a positive and almost affectionate way, meaning those who wander, traverse and explore…

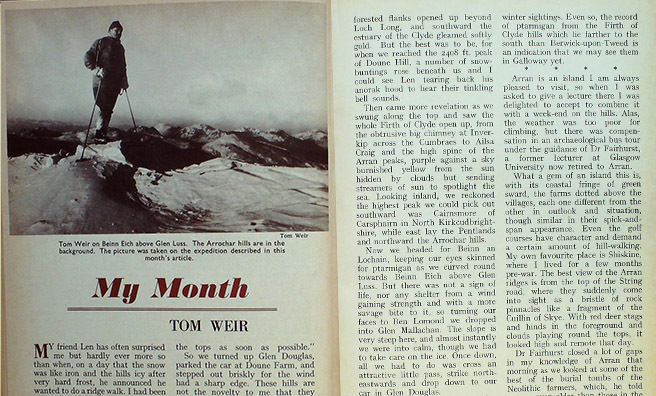

MY friend Len has often surprised me but hardly ever more so than when, on a day that the snow was like iron and the hills icy after very hard frost, he announced he wanted to do a ridge walk. I had been talking to him about the ptarmigan reported to me by a shepherd on the Luss Hills, and it had put him in the notion of stravaiging over tops he had not been on for twenty years.

I packed rope, crampons and ice-axes just the same, thinking he might change his mind as we drove up Loch Lomond. But he was adamant.

“No, I don’t want a cold gully. I want to get up there on the tops as soon as possible.”

So we turned up Glen Douglas, parked the car at Doune Farm, and stepped out briskly for the wind had a sharp edge. These hills are not the novelty to me that they were to Len, for I ski on them every winter when the powder comes and the steep, grassy slopes give excellent running. Today, however, the snow patches were so hard you could hardly kick a step, and every pool and wet place was hard frozen.

Len had forgotten these hills were so marvellously placed for views until the rocky knobbles of Argyll’s Bowling Green and its forested flanks opened up beyond Loch Long, and southward the estuary of the Clyde gleamed softly gold. But the best was to be, for when we reached the 2408 ft. peak of Doune Hill, a number of snow- buntings rose beneath us and I could see Len tearing back his anorak hood to hear their tinkling bell sounds.

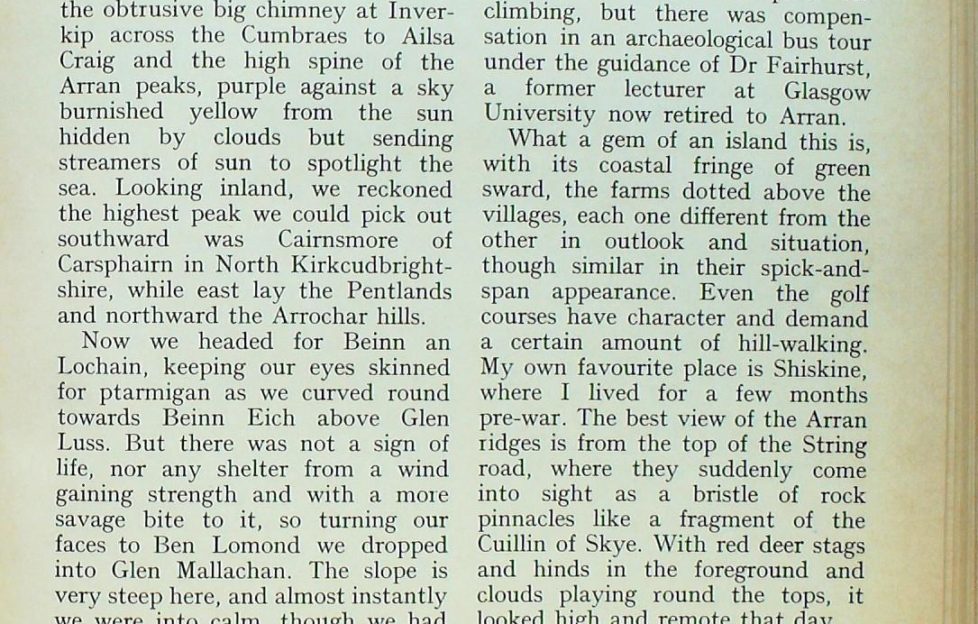

Then came more revelation as we swung along the top and saw the whole Firth of Clyde open up, from the obtrusive big chimney at Inverkip across the Cumbraes to Ailsa Craig and the high spine of the Arran peaks, purple against a sky burnished yellow from the sun hidden by clouds but sending streamers of sun to spotlight the sea. Looking inland, we reckoned the highest peak we could pick out southward was Cairnsmore of Carsphairn in North Kirkcudbrightshire, while east lay the Pentlands and northward the Arrochar hills.

Now we headed for Beinn an Lochain, keeping our eyes skinned for ptarmigan as we curved round towards Beinn Eich above Glen Luss. But there was not a sign of life, nor any shelter from a wind gaining strength and with a more savage bite to it, so turning our faces to Ben Lomond we dropped into Glen Mallachan. The slope is very steep here, and almost instantly we were into calm, though we had to take care on the ice. Once down, all we had to do was cross an attractive little pass, strike north-eastwards and drop down to our car in Glen Douglas.

Ptarmigan seem to be colonising ever southward, but there is not yet a breeding record from the Luss Hills, though they have now been proved to breed in Cowal, and Len found a nest on Ben Ledi two years ago. They have still to be proved as breeders on the Arran hills despite winter sightings. Even so, the record of ptarmigan from the Firth of Clyde hills which lie farther to the south than Berwick-upon-Tweed is an indication that we may see them in Galloway yet.

Remembering Arran

Arran is an island I am always pleased to visit, so when I was asked to give a lecture there I was delighted to accept to combine it with a week-end on the hills. Alas, the weather was too poor for climbing, but there was compensation in an archaeological bus tour under the guidance of Dr Fairhurst, a former lecturer at Glasgow University now retired to Arran.

What a gem of an island this is, with its coastal fringe of green sward, the farms dotted above the villages, each one different from the other in outlook and situation, though similar in their spick-and- span appearance. Even the golf courses have character and demand a certain amount of hill-walking. My own favourite place is Shiskine, where I lived for a few months pre-war. The best view of the Arran ridges is from the top of the String road, where they suddenly come into sight as a bristle of rock pinnacles like a fragment of the Cuillin of Skye. With red deer stags and hinds in the foreground and clouds playing round the tops, it looked high and remote that day.

Dr Fairhurst closed a lot of gaps in my knowledge of Arran that morning as we looked at some of the best of the burial tombs of the Neolithic farmers, which, he told us, are even older than those in the Mediterranean area. Nor were we allowed to pass a wee grassy hump at Lamlash. It marks the spot where the minister of the parish addressed North Glen Sannox emigrants forced to leave to make way for sheep.

Past Kildonan Fort we looked at the remnants of the 14th century castle, a ruin which regrettably cannot be preserved because there is no cash for it. Pladda with its lighthouse and two cottages looked very close from here, as did Ailsa Craig. At Shannochie we saw the only thatched house left in Arran— a post office.

It was nice to see Drumadoon again, near where I once lived. I had not realised then that here is a 12-acre Iron Age enclosure which has never been excavated. But I did remember the challenging wee pinnacle which I used to climb beside the cave where Bruce lived for a time. This is a good fanning corner, and many a back-breaking day I spent gathering potatoes, digging pits for them, and covering them with rushes. The emphasis on this crop is a thing of the past. The fields are in pasture now for cattle and sheep.

In the evening I accepted an invitation to Brodick Castle from my old friend John M. Forgie, who told in the January issue of this magazine how he left his job as Art Editor of The Scotsman to be the Custodian here (” Home Is a Castle.”). He lives in the top flat, and loves it, though the work is more demanding in time than any newspaper office. That evening the Music Society were having a song recital in the drawing-room, and about a hundred gathered to hear a rich contralto and superb piano performing in an elegant setting of glowing oil paintings, fine carpets and exquisite furniture.

John welcomed the guests and helped his wife to serve tea and coffee at the interval, with never a word about the worry on his mind. For as we were having dinner the recently repaired roof had begun to leak, and the evening became a sprinting match with basins and buckets, John braving the darkness and the rain slashing horizontally in a gale to go out with a torch to assess why the roof wasn’t coping.

And as I drove away into the storm back to Brodick he told me not to expect the boat until late, and not to linger over an early breakfast.

“It only takes a wee puff of wind to stop the Caledonia, and you won’t be going back to your car at Ardrossan. They’ll take you to Gourock, and you would have an hour on the bus after that.”

It was wise advice, but I was not unduly worried, for it was a fine morning with a touch of new snow on the peaks and the red bracken of Glen Rosa vivid above the houses glistening round Brodick Bay.

In my philosophy, the winter traveller has to be prepared to put up with some inconvenience, whether it be fog or icy roads or both, which was my lot when I set off for Dollar one slippery morning, giving myself plenty of time to be there at 10.30 on one of the three shortest days of 1975. I found it a stimulating drive, as from fog I would emerge into sunshine, see the big whale-back of the Campsies bulging above the hanging mists, then plunge into fog again.

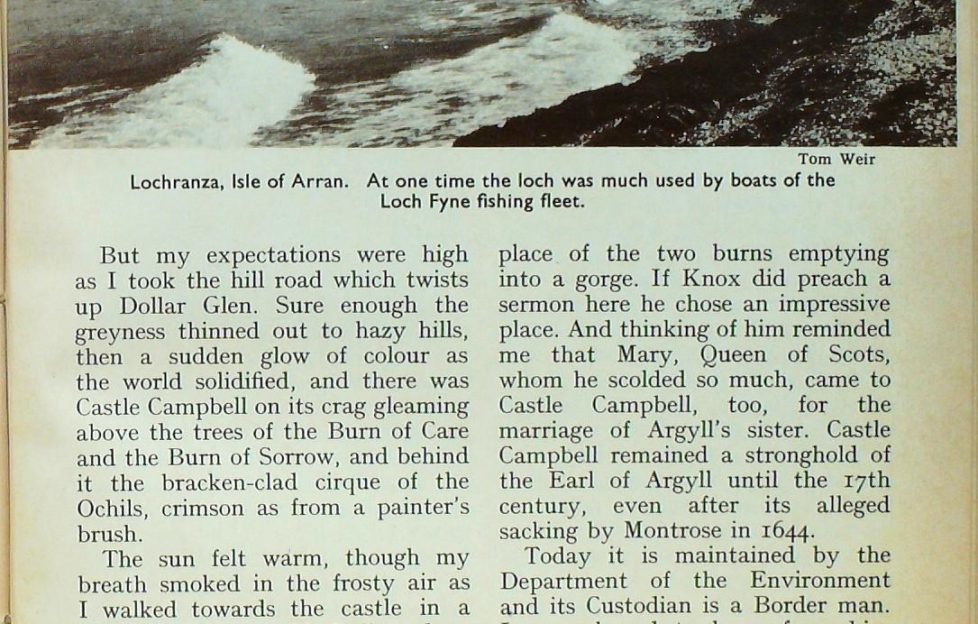

But my expectations were high as I took the hill road which twists up Dollar Glen. Sure enough the greyness thinned out to hazy hills, then a sudden glow of colour as the world solidified, and there was Castle Campbell on its crag gleaming above the trees of the Burn of Care and the Burn of Sorrow, and behind it the bracken-clad cirque of the Ochils, crimson as from a painter’s brush.

The sun felt warm, though my breath smoked in the frosty air as I walked towards the castle in a soundless world. Of Dollar there was nothing to be seen, only a cloud pall, so it was easy to imagine yourself back in the Campbell days of the 17th century when Royalist Montrose was hunting the Campbell Covenanters, though there is no decisive proof that it was his troops who sacked the castle.

Paths for all?

There is some sense in having a path from Aviemore to Elgin which would open up a walking route over fine country away from motor cars; but why bring in Glen Tilt and the Lairig’Ghru, where adequate paths already exist for those with the know-how to walk them ?

Adam Watson and I have been talking it over with very many hillmen and we all reach the same conclusion. We object on the following grounds :

(a) The Glen Tilt and Lairig Ghru paths are there, and open to everybody.

(b) Designation will involve extra facilities which will remove the challenge of this fine route rising to 2700 feet.

(c) Regulations and less individual freedom are a likely consequence.

(d) Designation and publicity will attract many inexperienced people, thus leading to more deaths and accidents.

(e) It is inappropriate to bring new developments into a National Nature Reserve.

The basic argument against the route over the Grampians is that there is no escape from it. Once you are over the top at 2700 feet you are committed, and it can be winter any day in the year up there. Hill-men enjoy that very aspect—the challenge; something noteworthy to do, where you really are out on a limb, nothing urbanised, no wardens looking after you. The map and your preparedness of mind and equipment are enough. You rely on your own fitness, and self-confidence built up through experience.

Why then change the status quo ? Why even think about it? If the argument is to make it easier for people, then who are they? The less qualified, the unfit, the youth leaders and their following of school-boy and girl crocodiles? And what about the conservation aspect? The Countryside Commission are supposed to have a brief for this, too, and they should know that the best protection of a unique and dangerous wilderness is to leave it unbuilt on and unmarked for those who don’t mind getting their feet wet, and who know how to avoid getting lost.

What I do applaud is the initiative of the Scottish Rights of Way Society, an organisation financed and organised by outdoor folk with the aim of preserving the old paths and the rights of the walkers using them. This society is now working to get a Great Glen path for walkers following the old rail track and canal towpaths, &c., so that back-packers can enjoy the traverse of the great trench running from Banavie to Inverness in peace, without having to dodge traffic and endure its noise. Anyone who feels like supporting the society most likely to do good for long-distance walkers should write to the Secretary, Scottish Rights of Way Society, 6 Abercrombie Place, Edinburgh. The subscription is only 50 pence annually, for which you get some literature, too.

What really pleased me during the month was to hear about proposals being investigated now to form a Country Park of the Kilpatrick Hills, stretching right across from the Clyde to the Stockie Muir. This is a fine region and I had not visited it for some time, so I was glad to accept an invitation from Dr Ian MacPhail and have a stravaig over it. I knew I was in for a good walk as Ian is not only a mountaineer but our local historian.

We began at Overtoun House, high above Dumbarton, in fine parkland on a sunny afternoon with the grey cliffs of the Lang Craigs rising above an inviting ledgeway of green which was our path to the top at 1,000 feet.

“Now look at that,” said Ian with pride as he swept his hand over the estuary of the Clyde to the Cowal hills, and east over Loch Lomond to the big hills of Perthshire dappled with snow.

To my surprise I found quite a bit of Forestry Commission plantings just over the rim, where we had our first view of the Rannoch Moor, an expanse of brown bumps with wee lochans. Our route took us to the first of them, the Black Linn, then in a sweep round to come over the top of the Doughnot Hill at 1228 feet.

Ian, a keen walker on the Lang Craigs and Kilpatricks all his life, was remembering how he used to beat grouse up here, when he was not dodging the keepers, who, in pre-war days, tried to keep the locals off the Overtoun approach.

I remembered, too, how jealously the Stockie Muir approach was keepered, too, and the same held true for the Clydebank flank. However, we were agreed that it had been good fun outwitting the keepers to win the freedom of these hills whose most famous feature is “The Whangie”—that curious fracture in the rocks said by some experts to have been the result of an earthquake.

It was where I went next, approaching from the summit of the Stockie Muir, although we could have walked to it in an hour and a half from Doughnot Hill. But the approach is easier from the 600-ft. summit of the Drymen road and the route is way-marked. That day I had a grand wee scramble up the miniature Cuillin ridge and along its crest, looking out over the whole Highland line from west to east.

A Country Park would not spoil the Kilpatricks. Close to main centres of population, it is the ideal lung, offering rewarding views and the pleasure of the heights for a relatively modest expenditure of effort. A marked path or two across the tops would be necessary if the park were to become a reality, but they should be kept to a minimum consistent with safety. Route- finding can be tricky on the plateau in misty weather.

And it was to Rannoch Moor I went next, stopping off to talk to shepherd Norman McLennan, whose hired is part of the 3000 acres of Achallader Farm near Bridge of Orchy. His is high and difficult ground, but he shook his head when I asked him if he carried a map and compass in bad weather.

“No, I was lost only once, a long time ago. But not for long, for I heard the whistle of the West Highland tram that passes the farm and I knew the direction to make for.”

The farm is beside Achallader Castle which I had never looked at before, so we had a walk among the old tombstones of the Fletchers under the gaunt gable of the towering ruin.

“Aye,” said Norman, “they say that Campbell of Glenlyon stopped here on his way north to carry out the Massacre of Glencoe. And it was because of the Treaty of Achallader that MacLain of Glencoe had to go to Inveraray to take the oath of allegiance. He took the oath, but the massacre was carried out just the same.”

I looked up the date when the castle was supposed to be built as a Campbell stronghold — the year 1600 — just 92 years before the deed in Glencoe when the Campbells were to besmirch their name on February 13 on a cruel, snowy morning.

After leaving Norman I had a chat to Iain Macrae, deer-stalker on the Black Mount Forest, and a keen Glencoe skier whom I meet often enough on Meall a’ Bhuridh in company with his wife and three children. Iain has been at Black Mount for 13 years, and he looks forward to the snow so much that last year he took his annual holidays so that he could spend it ski-ing with the family over Easter in Glencoe and the Cairngorms.

His children have been brought up to ski, and the good news this year is that his oldest boy Martin has been awarded a grant to go race-training in Austria. Having seen this 15-year-old in action over the years, I think there is a future “white hope” here. Iain is a Kintail man, but likes it very much at Loch Tulla, with Fort William less than an hour distant across the new Ballachulish Bridge, while, if he has to go to Glasgow, he can be there in an hour and a half.

But accessibility has its problems, too. The bane of life on the Glencoe road this winter is poaching by cross-bow at night. Iain told me how it is done. The poachers pick out a deer feeding along the roadside and blind it with a spotlight, fit a steel arrow to their cross-bow, and let fly. The weapon is soundless, and if they make a kill the deer is lifted quickly into the vehicle and they are away. But if they fail to kill they may leave behind them a very sick or maimed animal.

Luckily the police have been vigilant, and some of the culprits have been caught, but it means that keepers have to be constantly on the prowl and miss some sleep—no joke when you have to be up early like Iain, who drives his children ten miles to Kingshouse so that they can catch the school bus to Kinlochleven. However, as Iain puts it, “There’s never a dull moment here. It’s a great life.”

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, where a new column is published online every Friday.

More from 1975

More from 1976

- February 1976: Stravaiging The Tops

More instalments every Friday