Tom Weir | A Spring Morning, Tales of the Drovers, and The Carron Valley

In his column for our March, 1976 edition of The Scots Magazine, Tom Weir considers the delights and dangers of the Scottish mountains, and explores he history behind the old drover’s roads around Falkirk

A Spring Morning

For the most magical of contrasts, give me a spring morning in my own village, with the skylarks singing over the brown furrows of the ploughed fields and, above the green shores of the loch, the Highland hills sparkling with winter snow. But it makes me feel unsettled, imagining how good the ski-ing must be after a night of frost, and realising I will regret having missed it if I stay down to enjoy the warmth and take a walk along the shore.

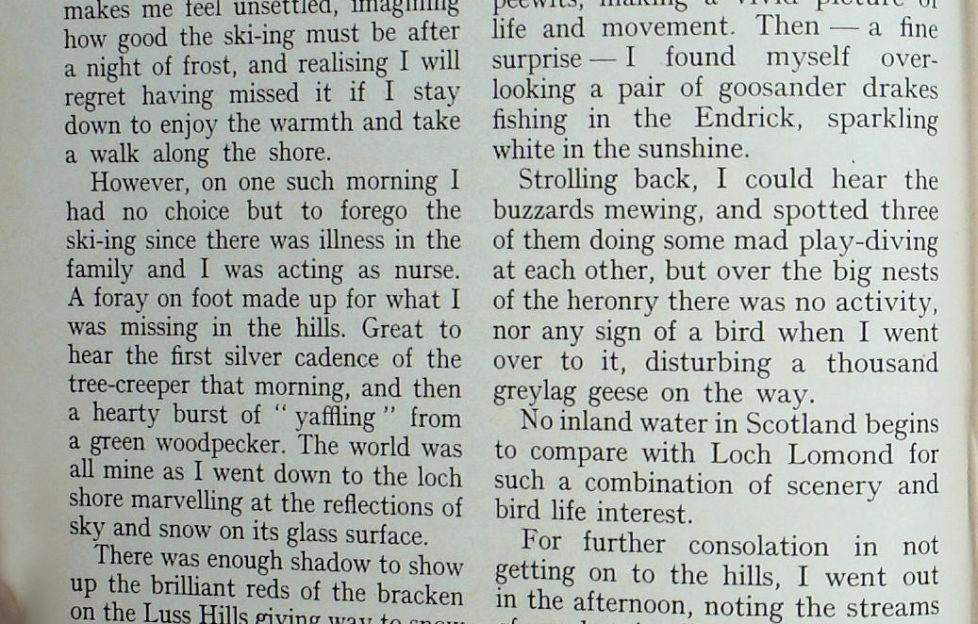

However, on one such morning I had no choice but to forego the ski-ing since there was illness in the family and I was acting as nurse. A foray on foot made up for what I was missing in the hills. Great to hear the first silver cadence of the tree-creeper that morning, and then a hearty burst of “yaffling” from a green woodpecker. The world was all mine as I went down to the loch shore marvelling at the reflections of sky and snow on its glass surface.

There was enough shadow to show up the brilliant reds of the bracken on the Luss Hills giving way to snow against which I could see geese moving in a black line. Nearer I could hear the churring of long-tailed tits and was delighted by the sight of them flighting over a bit of open marsh, parachuting their long tails between wingbeats. They led me to four siskins perched on a willow, two cock birds, green as peas, and two streaky hens.

As I came over a rise, about eighty white-fronted geese took to the air below me, along with a flock of whistling wigeon and a mob of peewits, making a vivid picture of life and movement. Then — a fine surprise — I found myself over-looking a pair of goosander drakes fishing in the Endrick, sparkling white in the sunshine.

Strolling back, I could hear the buzzards mewing, and spotted three of them doing some mad play-diving at each other, but over the big nests of the heronry there was no activity, nor any sign of a bird when I went over to it, disturbing a thousand greylag geese on the way.

No inland water in Scotland begins to compare with Loch Lomond for such a combination of scenery and bird life interest.

For further consolation in not getting on to the hills, I went out in the afternoon, noting the streams of cars buzzing like bees after honey on the scented pussy willows. I took the peaceful drove-road over the Cameron Muir for the splendid view stretching from the Blane Valley into Perthshire and west by the Fintry Hills over a multitude of summits stretching into Cowal.

On the heights of Glencoe, Hamish MacInnes was having his busiest week-end for eight years as these marvellous conditions lured climbers “beyond their experience and fitness” — Hamish’s words. Mary McKerrow, who died after sliding 1000 feet, had won the Duke of Edinburgh’s Gold Award for hill-walking last November. She died as a helicopter was racing to lift her from the Lost Valley of Bidean nam Bian.

Miss McKerrow was an Aberdeen University student. Not far away, a student from Glasgow, Sheila Slatford, suffered multiple injuries in a slide of over 100 feet and was rescued by helicopter in a bold piece of gully flying. Maclnnes noted that neither was wearing crampons, and the Glasgow girl did not have an ice axe.

In the Cairngorms, Malcolm Brown, another student, fell 200 feet in Coire an t’Sneachda overlooking Loch Morlich. He died next day of severe head injuries. Other rescue parties were out searching on Ben Nevis, and climbers were even getting benighted on Meall a’ Bhuiridh, the skier’s mountain which gives the most exciting running in Scotland.

I had a good idea of what conditions were like for I had been to Meall a’ Bhuiridh ski-ing just a few days before, and they were really exciting, low temperatures, hardly any wind, not nearly enough snow to cover the rocks. There seemed no need for warnings of hazards when they were so obvious.

Sun and cloud made the views exciting, with Nevis and the Mamores bulging above the vapour from time to time, and great colour contrasts between the brown of Rannoch Moor and the sparkling summits. Good men took some mighty falls that day as skis got caught on hidden rocks. Noting the stretcher moving on the main runs, I kept telling myself to be careful.

But confidence gradually built up, and by afternoon I felt I had the measure of the conditions, and, for the last run of the day, decided to have a go at the “Spring Run” with Chris Ford, a keen mountain skier who loves a challenge. I felt just a bit apprehensive, since no one else appeared to be venturing on it that day. Chris led the way. Icy, steep and intimidating looking, it was a place not to fall or one would keep sliding. After the first turn or two on the tapering bowl, I let my skis take over, relaxed and allowed the bliss of the moment to sink in, as we shot through rocks, side-slipped down the edge of a bulging cornice, hammered across the gully, flicked the skis round and came racing back for a long traverse which got faster and faster. Knees ached and a turn was welcome.

And as we ran we could glance up to the Buachaille Etive, its rocks warm in the sunset in contrast to the powder on its ledges. Gloriously, too, we were able to ski right across the plateau and down to within 50 yards of the foot of the hill, the perfect finish to one of the best descents I have had in years.

Tales of the Drovers

A few days later, on the drove-road of the Cameron Muir, I was pleased to meet the Wyllie family, father and sons bringing sheep along the road to their farm at Wester Cameron.

“We’re giving the hoggs a spring dip tomorrow, so that’s why we’re at it today,” said the boss.

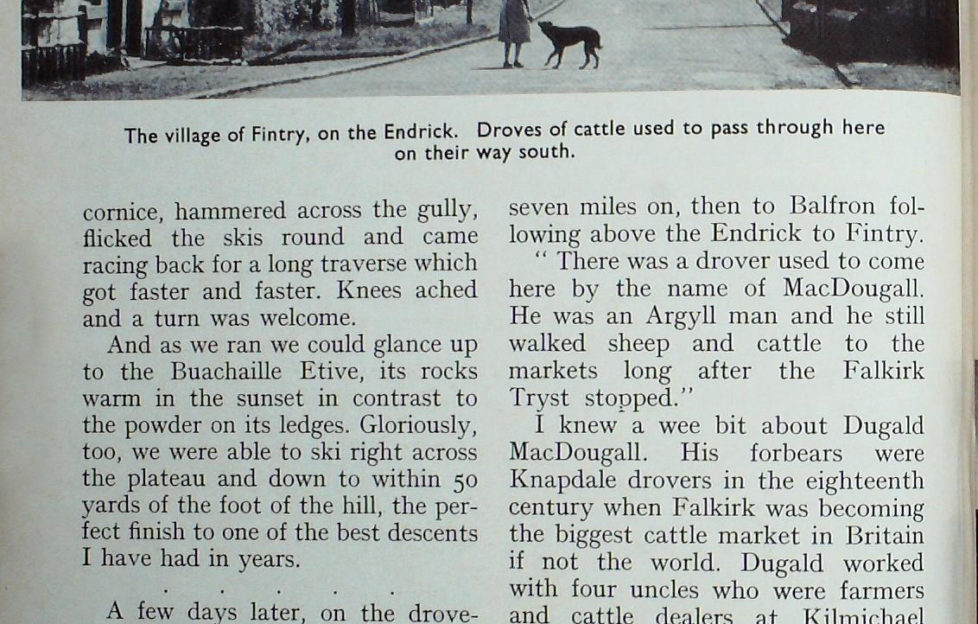

“If you’d been going the other way I would have thought you were going to the Falkirk Tryst,” I said. He laughed: ” Aye, this must have been a busy road a hundred years ago. They were making for Killearn seven miles on, then to Balfron following above the Endrick to Fintry.

“There was a drover used to come here by the name of MacDougall. He was an Argyll man and he still walked sheep and cattle to the markets long after the Falkirk Tryst stopped.”

I knew a wee bit about Dugald MacDougall. His forbears were Knapdale drovers in the eighteenth century when Falkirk was becoming the biggest cattle market in Britain if not the world. Dugald worked with four uncles who were farmers and cattle dealers at Kilmichael Glassary. Born in 1866 he died in 1957, but not before recording his memories of the droving trade for the School of Scottish Studies.

The general story of Scottish droving has been well written-up in A. R. B. Haldane’s splendidly- researched The Drove Roads of Scotland. The Highlands and Islands could rear the young cattle, but hadn’t the winter feed to fatten them. Two events happened at the right time to create the opportunity of trade. The first was the Union of 1707 and the arrival of more settled times. The second was the growth of London, Midlands and North of England towns, not to mention the wars lasting from 1727 to 1815 which meant a demand in England for lean Scottish cattle for fattening.

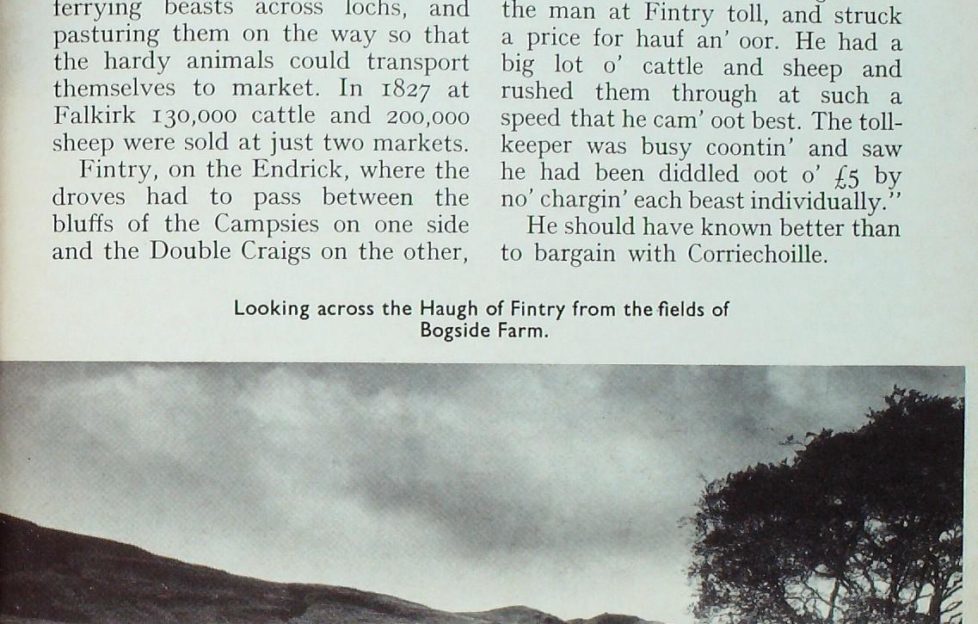

The wild clansmen were used to lifting cattle and walking them through the glens to their hideout, so it was a natural evolutionary step for them to become drovers, fording wild mountain torrents, ferrying beasts across lochs, and pasturing them on the way so that the hardy animals could transport themselves to market. In 1827 at Falkirk 130,000 cattle and 200,000 sheep were sold at just two markets.

Fintry, on the Endrick, where the droves had to pass between the bluffs of the Campsies on one side and the Double Craigs on the other, was a place I reckoned I might meet some old farmer who could tell me more about the Falkirk Tryst.

And I found the very man in Bob Aitken who farms Bogside.

“I mind an uncle o’ mine walking a filly hame that he had bocht at the Falkirk Tryst. It was maybe aboot 1895, but it wisnae much o’ a fair by that time. And I mind a story I heard about Corriechoille — you’ll have heard o’ him, the biggest o’ the drovers. He made a bargain wi’ the man at Fintry toll, and struck a price for hauf an’ oor. He had a big lot o’ cattle and sheep and rushed them through at such a speed that he cam’ oot best. The toll-keeper was busy coontin’ and saw he had been diddled oot o’ £5 by no’ chargin’ each beast individually.”

He should have known better than to bargain with Corriechoille.

We talked about the cotton mill, built around 1796 and using water power from the hills to keep 20,000 spindles turning.

“It failed, and so did the wool mill. They were ower far frae Glasgow and the coal seams.”

More surprising, though, is that the distillery should have failed, with excellent Campsie water producing 70,000 gallons of malt whisky from 1816 onwards. You can see the ruins behind the garage on the main street which was built for the cotton workers.

The Carron Valley

After that I took a stroll into my own historical period, going along the Carron Valley, leaving the Endrick where it cuts north into the hills, and where a large sheet of water ringed by forests begins, mounting up the slopes of the Meikle Bin. It made me feel an old codger to see such a mature land-scape, for I remembered the meadow hay and the 300 Highland bullocks which used to graze when there was no loch or forest. Now the trees have grown up and are being harvested for chipboard or the pulp mill.

I know the farmers were very dis-pleased at such good land being flooded and planted with trees, but agriculture was in the doldrums in 1938 when the Duke of Montrose died and some of his estate here went in death duties. Today there is a forestry village at the dam, and additional workers travel in from Denny. I have to admit that scenically the place is more interesting now than it used to be, with whooper swans and duck on the loch, and hen harriers and short-eared owls nesting on the hills.

So, the old drove road has disappeared from this stretch, overgrown or under water, but it can be traced uphill, and I think I followed it for a bit east of Endrick Bridge past Fintry Castle ruins to Spittal Hill Farm which is mentioned in the droving accounts.

I was thinking, too, of the Carron Iron Works which was going full blast when the droving trade was at its height, smelting iron for use in the Napoleonic Wars, building the first steam engine for winding coal, and building an engine for the first steamship to be launched in the Carron River in 1789, so that soon the ships of the Carron Company were plying to London.

It is paradoxical that the Carron Iron Works should have been located at Falkirk, for its products were to outmode the droving trade as the age of the steamship and the railway was ushered in. Consider, too, that to keep the Iron Works supplied, whole forests, as far north as Glenmoriston, were being consumed for charcoal which had to be carried to Falkirk for extracting the iron from the ore.

And the Highlanders themselves were being pushed out of their cattle grounds by alien landlords to make way for sheep. So, instead of one big market like Falkirk, a whole lot of smaller markets were set up in the north to which drovers still walked their beasts though increasing numbers went by rail and ship. Another factor in the droving decline was the agricultural revolution, the introduction of the turnip and the rotation of crops for bigger yields, resulting in the breeding of bigger and better breeds of cattle which could be wintered, but could not stand the strain of walking great distances.

It has to be said that droving was only slightly less adventurous than clan warfare, so much so that the drovers were allowed to carry arms even when this was forbidden to other citizens in the Jacobite times. But robbery was only one danger. There were problems of floods at a time when most rivers were un- bridged, and in stormy weather there were risks ferrying cattle over storm- swept lochs.

Which brings me to a story of modern travel. Perhaps it could save a life or two. A party of cross-country walkers who had spent a night in a bothy were held up at a burn on the edge of a deep loch after a night of torrential rain. There was a house and boat visible on the other side, but they did not think to shout for help in crossing.

Instead, three of them, wearing their nylon-pack frames, linked themselves near the loch-edge so that each would be a support for the other, as the best manuals advise. They were swept away. A fourth man dived in to try to rescue them, without his pack. The three who were wearing their packs were rescued by the man in the house.

Their clothing, sleeping bags, and odds and ends in the packs had kept them afloat. The fourth man had gone under and his body has not, as I write, been recovered.

The lesson to be learned is that your pack, with week-end kit in it, if made of waterproof material, will keep you afloat when otherwise you might sink unless you are a strong swimmer. This was well known in the Army, when troops on river- crossings wrapped their packs in waterproof groundsheets and, resting their arms on the packs, kicked with their legs to get across-stream.

On the particular day when this incident happened, the party would have been wiser not to risk a crossing in view of the amount of rain that had fallen. Luckily, my friend with the boat was able to bring the others across after he had rescued the three struggling hikers.

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, and a new column is published online every Friday.

More from 1975

More from 1976

- April 1976: A Spring Morning, Tales of the Drovers, and The Carron Valley

More instalments every Friday