Tom Weir | Ailnack Gorges and Beyond

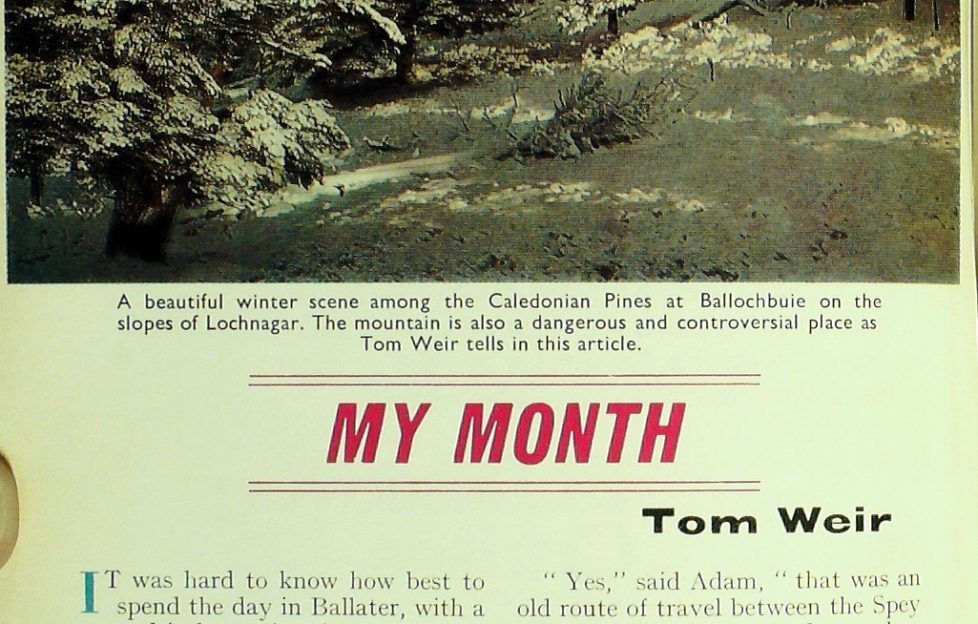

In his first article of 1979, Tom Weir hikes through the Gorges of the Ailnack, gets caught up in controversy surrounding the Lochnagar corrie, and discovers a very unusual cairn…

IT was hard to know how best to spend the day in Ballater, with a grey drizzle setting in and clouds moving down ominously, blotting out the hills. Then Adam came up with a bright suggestion.

“How about driving over the Lecht to Tomintoul for Strath Avon and cutting over to the gorges of the Ailnack? I don’t know if you’ve been there, but even in poor visibility it’s dramatic.”

I told him I had seen the gorges before, but only from the Caiplich side, walking in from Dorback Lodge on the Abernethy side of the Spey.

“Yes,” said Adam, “that was an old route of travel between the Spey and the Don. In the days when wooden utensils were in demand, the stuff made in the Abernethy forests was carried by way of the Ailnack gorges to Delnabo. It’s a fascinating bit of country, very seldom visited, but sometimes people lost on the Macdhui side of the Cairngorms land up there and have no idea where they are. It’s so big, featureless and empty.”

Some of the best moors in Scotland…

He had said enough, and off we drove into the mist and drizzle, with a few stops before Cock Bridge to watch red grouse at the roadside filling their crops with grit to aid digestion. The big moors here are some of the best in Scotland, and plenty of birds seemed to have escaped the guns. Past the new ski lift at 2000 feet and we were soon spinning through the murk to deserted Tomintoul, where we swung left for the locked gate just south of Delnabo.

With the engine shut off we realised just how steady was the drum of rain on the roof.

“Ah, well, let’s have a drink of tea and eat the meat pies we bought in Ballater,” I said. While we were chatting and munching, the rain was not only easing up, but by the time we had finished, the clouds were lifting and some colour was beginning to flood into the winding river strath.

This was real luck, and we wasted no time in pushing west over the hill shoulder immediately above us to come down over the heather and find ourselves on the precipitous edge of the ravine, the houses of Tomintoul and the braes of Glenlivet framed beyond.

Now I had the impression of a high, perched village, but agricultural, not at all bleak, hence the Gaelic, Tom an t-Sabhail — Hillock of the Barn.

Now we turned our attention to the details of the gorge, which is hung at this point with green juniper in the hollows and tall larches on a ridge with the burn sandwiched in the narrows below. We found it hard to judge the composition of the very steep grey sections. Was it rock or scree? The only way to find out was to go down, and we found it was material so compressed that it was a sort of pudding stone, separate stones firmly embedded in the scree, making it into a sort of rock.

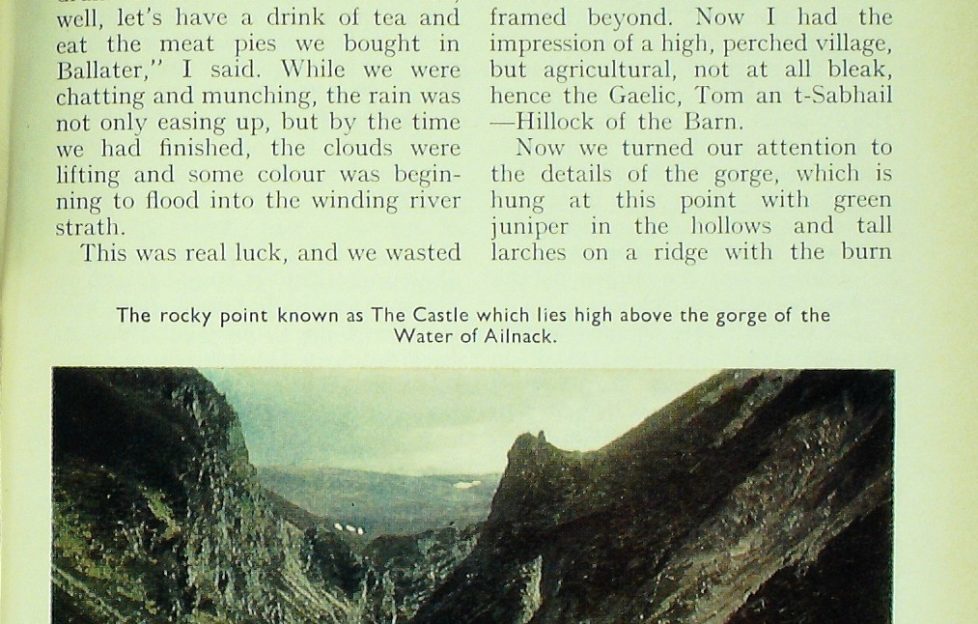

What made the gorge so enjoyable to traverse was the constantly changing scene as we followed up its twists and turns—none too easy to keep on the south edge because of the depth of heather on the very lip of the ravine. It became steadily more precipitous as we went, yet there were always trees, silver birches, aspens, willows, even Scots pines sheltering between the steep craggy walls. There were good rock buttresses, too, just too steep and lush with vegetation to be attractive to climbers, but the Alpine botany looked potentially rich.

The Castle, where the photograph on page 425 was taken (main pic above) marks a turning point in the gorge, a shift of direction in the flow of the stream from east to north-east. The sharp loop that the gorge makes at the point of change is at a little col beyond which Glen Loin cuts in from the direction of Inchrory in Strath Avon.

That col and change of direction at the Water of Ailnack is of special interest, for in former times the drainage of the western part of the river was into Glen Loin, before it cut a new course towards Tomintoul.

The gorges were cut by the action of melt-water pouring out of shrinking glaciers at the end of the Ice Age, every stream compelled to follow old hollows, digging out V-shaped gorges below The Castle and for most of the half a dozen miles to Delnabo. We struck directly across the hill for Strath Avon, staggering in the gale-force wind which had risen but enjoying the sight of a pair of peregrine falcons letting themselves be tossed skyward before plummeting down in power dives like stones, to be wafted aloft again when they opened their wings.

The Ancient Byways

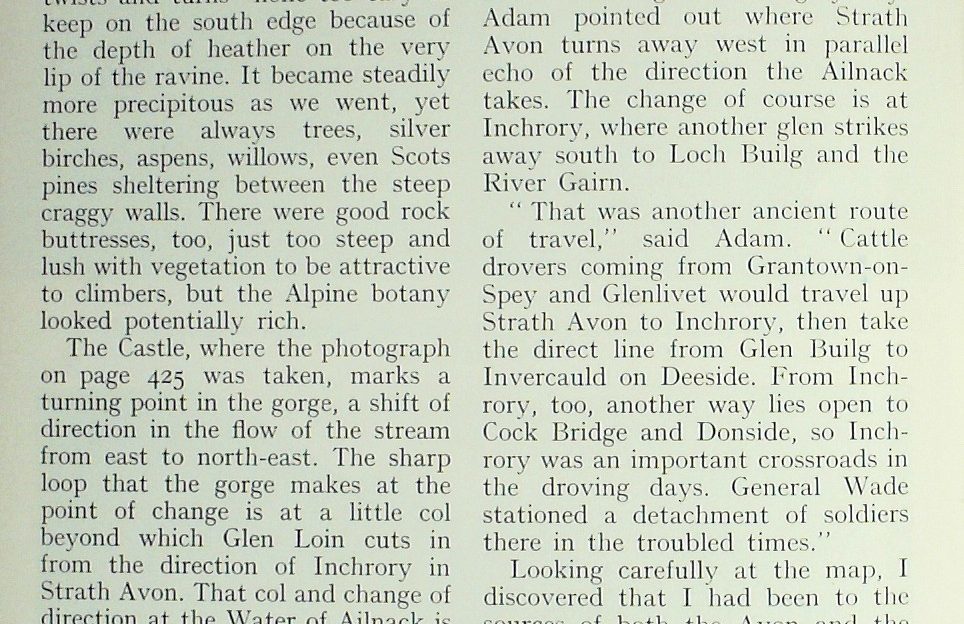

Snug in the heather watching them, we set the map so that I could sort out for myself the tangle of this complicated topography now that the warty tors of Ben Avon and the rocks of Beinn a’ Bhuird stood black against the grey sky. Adam pointed out where Strath Avon turns away west in parallel echo of the direction the Ailnack takes. The change of course is at Inchrory, where another glen strikes away south to Loch Builg and the River Gairn.

“That was another ancient route of travel,” said Adam. “Cattle- drovers coming from Grantown-on- Spey and Glenlivet would travel up Strath Avon to Inchrory, then take the direct line from Glen Builg to Invercauld on Deeside. From Inchrory, too, another way lies open to Cock Bridge and Donside, so Inchrory was an important crossroads in the droving days. General Wade stationed a detachment of soldiers there in the troubled times.”

Looking carefully at the map. I discovered that I had been to the sources of both the Avon and the Ailnack without realising it, when walking from the Shelter Stone of Loch Avon by the Lairig an Laoigh and taking in the top of Bynack More as I went. How these cattle drovers in the days before maps must have known their country, using these eastern passes and even the Lairig Ghru! Having crossed from Speyside over to Deeside, they might have continued by Glen Muick across the hills to Glen Clova to reach Angus—an adventurous life.

Strath Avon must have been a populous place in the old days, judging by the ruins we passed on our way back to the car, through superb river scenery, with grassy haughs and woods backed by rounded, heathery hills.

“Here’s another wee poem for you,” said Adam as we looked down on a dipper bobbing on the stones, Bynack white bib flashing as it splashed in and out of the water.

The watter o A an it rins sae clear

Twad beguile a man o a hunder year.

We would have lingered by its pools but dusk was falling and the rain was settling in by the time we reached the car.

A spot of controversy with a lithe,

black-bearded giant

The good luck stayed with us, for after a wild night the morning held the promise of sunshine as we headed out of Ballater for Lochnagar. Little did I know that even before I could don my climbing boots I would be involved in controversy with a lithe, black-bearded giant whose arrival at the Glen Muick car park coincided with ours.

The sight of my face seemed to galvanise him to action.

“Tom Weir?” It was not so much a question as a demand. I nodded in agreement. “Well, I want your opinion. You’ve heard about this hut business in the corrie of Lochnagar. Do you support the idea, or are you against it?”

Adam had told me that some private individuals were building a hut in the corrie as a memorial to a climber who had been killed, and we had agreed that it wasn’t a good idea.

So I told my interrogator that I was against the idea on principle, and gave as my reasons that anything which urbanises the mountains reduces their splendour, especially in a corrie like Lochnagar which is one of the finest in Scotland. The other point I made is that it is not a long walk into the corrie from Glen Muick—nor is it a big climb.

“Well,” he said, “I disagree with you, for it was my brother who fell 6oo feet last April and died of exposure in a blizzard. If there had been a hut he would be alive today. It took eight hours to bring help. I’ll tell you the kind of hut another brother and myself were trying to build—just a stone box four feet high to take the first-aid kit that’s always been kept in the corrie. All we had in mind was leaving enough room to shelter an injured man. The structure would have been tiny, and built at an angle so that water would drain away. It would have been of natural stone, like its surroundings.

“Prince Philip approved of the idea. John Robertson, the deerstalker who has helped many climbers in need, approves of the idea, but not the diehards, whoever they are.”

I agreed what he had told me put a new complexion on things, for a shelter to house the first-aid equipment and provide an emergency corner for a man is hardly the same thing as a hut. I asked him to come over with me and have a word with Adam Watson. Like me, Adam had not realised what David Niven and his brother Eric were trying to do on Lochnagar. So I waited with interest for his reaction.

Adam held to his view, and didn’t

mince his words.

“No, I don’t like the idea of any shelter. Any kind of roof will attract climbers, and will soon become another dump of tins and rubbish. I sympathise with your feelings for your brother, but I am against memorials, whether plaques or huts. Climbing on Lochnagar in winter is a high risk business and you have to accept it. I know the Etchachan Club feels this way, for I am a member of it.”

Turning to me for support, David Niven explained his views.

“Look, you know what winter climbing is like. You’ve had your falls; you know the dangers of avalanche or an ice-step collapsing. Once there were only a few winter climbers on Lochnagar, but now they come in droves from England as well as all over Scotland. The situation has changed since the early days.”

Eric and David Niven had reason to feel bitter, for the shelter on which they had laboured all summer was destroyed by persons unknown who were certainly hard climbers, and probably from Aberdeen. Well, I must declare my sympathy with the Nivens, and if think they have a good case, for Lochnagar has had a first-aid box in its corrie for many, many years, which is recognition of a need that is not normal on oither mountains. So why not accept a small stone shelter to house the box if men are willing to build it? I am not emphatic about the need for the shelter, but I am against those who were high-handed enough to destroy what had been built, even if they believe in a live and let die world.

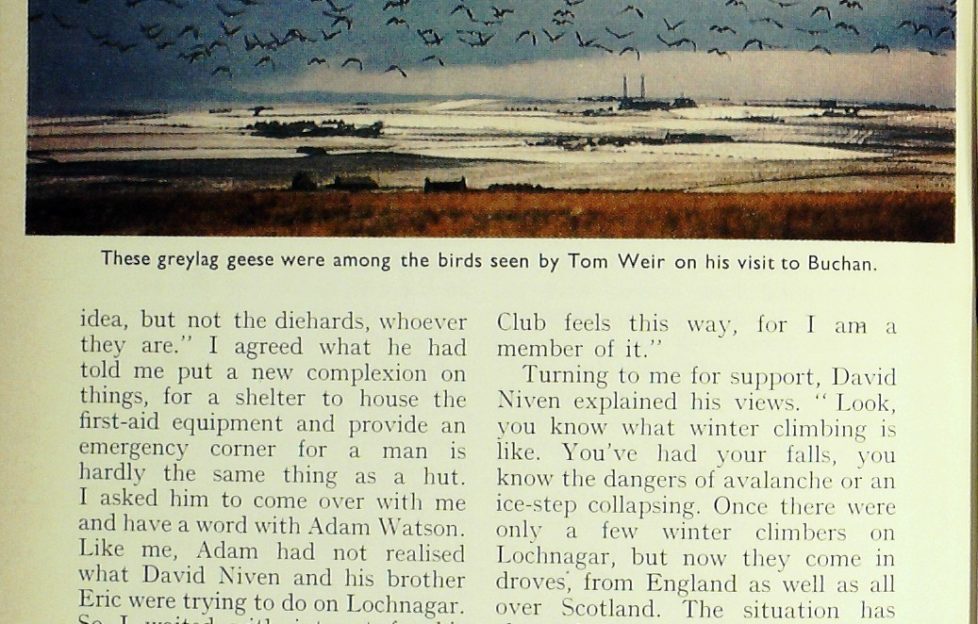

Emerging in treeless Buchan

For me a visit to the North-east is incomplete if I don’t get from the big woods of Deeside and the marvellous pines of Ballochbuie to treeless Buchan, and it was an eye-watering day with new snow on the hills when we motored up the coast from Aberdeen to look at the Ythan where it meanders from the big fields to enter the sea below the Sahara of the Sands of Forvie.

The north wind was Arctic that morning, but in the gleams of sun between stinging showers and rainbows the eider drakes glittered like snow, a pack of about 2000. Wherever you looked there were flighting birds, throngs of oyster catchers, redshanks, bar-tailed godwits, knots, turnstones, flocks of wigeon and mallard, herds of swans. Near at hand, there were tree sparrow and reed buntings in the whins at our side while skeins of geese passed overhead.

Our destination that night was Banff, where I was giving a lecture, and it was great fun to be in this most attractive of towns as guests of Dr and Mrs Peter Sharp. Cold, wet night as it was, we had a full hall for my talk, arranged by the Deveron Wildlife Club.

Banff is my idea of the perfect size of town to live in; its buildings are architecturally inspiring, it is situated above a fine bay, and inland there is a wonderful choice of country dominated by the triple peak of Bennachie 30 miles away.

I have had a good feeling for Banffshire for many a year now, but not until the trip described have I encompassed so much of it on one visit, getting up to its wildest gorges on the Ailnack, then following up its finest strath, Strath Avon, to come back across the moors of Tomintoul and finish up by visiting my old haunts on the line seabird cliffs of Troup Head and look down on Gamrie Bay and the perched fishing village of Gardenstown, one of the most thriving in Scotland. It was really all too much in too little time. I could have done with longer.

An Unusual Cairn

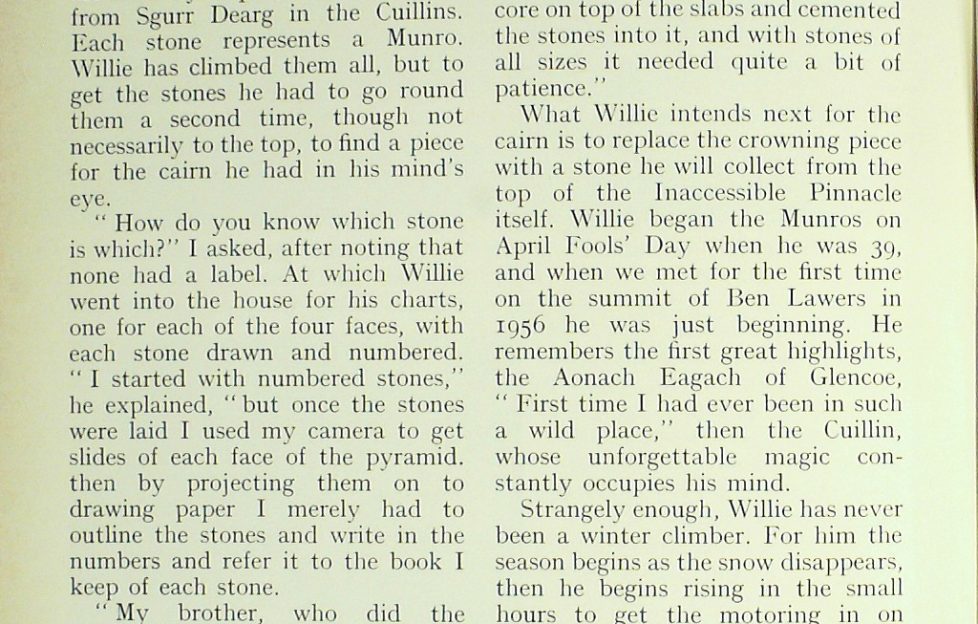

Once back home I went to meet my old friend Willie Shand at Crook of Devon, who took me into his garden to show me his labour of pure love, a cairn, faced with 280 stones in the form of a pyramid crowned by a point of rock taken from Sgurr Dearg in the Cuillins. Each stone represents a Munro. Willie has climbed them all, but to get the stones he had to go round them a second time, though not necessarily to the top, to find a piece for the cairn he had in his mind’s eye.

“How do you know which stone is which?” I asked, after noting that none had a label. At which Willie went into the house for his charts, one for each of the four faces, with each stone drawn and numbered. ” I started with numbered stones,” lie explained, ” but once the stones were laid I used my camera to get slides of each face of the pyramid, then by projecting them on to drawing paper I merely had to outline the stones and write in the numbers and refer it to the book I keep of each stone.

“My brother, who did the Munros with me, had built a similar cairn, but he had not recorded where the stones came from, so I learned from his experience. It took me 12 years to climb all the Munros and another three to four years to gather the stones. You can say that the bigger the stones are on the cairn the nearer they were to the road.

“Graham, my brother, is a builder, and my son Willie is a quantity surveyor, and they combined their experience to get the measurements right and decide the best way of going about laying the stones. I had sorted them out into piles of seventy and laid them out on the cellar floor in pyramidshape. So what we did was make a hole for the foundation about 2 ft. 9 ins. deep, level it with Arbroath slabs, and with an iron stake and a piece of string marked off the four corners for a 4-ft. high pyramid.

” To begin, we built up a rubble core on top of the slabs and cemented the stones into it, and with stones of all sizes it needed quite a bit of patience.”

What Willie intends next for the cairn is to replace the crowning piece with a stone he will collect from the top of the Inaccessible Pinnacle itself. Willie began the Munros on April Fools’ Day when he was 39, and when we met for the first time on the summit of Ben Lawers in 1956 he was just beginning. He remembers the first great highlights, the Aonach Eagach of Glencoe, “First time I had ever been in such a wild place,” then the Cuillin, whose unforgettable magic constantly occupies his mind.

Strangely enough, Willie has never been a winter climber. For him the season begins as the snow disappears, then he begins rising in the small hours to get the motoring in on empty roads, have long clays on the hills, and drive home again to Crook of Devon. On my visit to him we had a walk over the top of Ben Cleuch, but we covered not only Scotland but England, Ireland and Wales talking about Munros, for there is no peak over 3000 feet in these countries that Willie hasn’t climbed.

A great thing enthusiasm!

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday.

More columns

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.