Tom Weir | A Good Life On Gigha

In busy Tarbert, Loch Fyne, you couldn’t buy a fish supper, such was the throng of yachts whose crews had cleaned out the shop.

Sunshine and a south-easterly breeze had given a glorious finale to the Tomatin Trophy Series of races organised by the Clyde Cruising Club. I knew how good the days had been, for we were on our way home after a feast of non-stop sunshine on the Isle of Gigha.

“You picked the best weather of the year,” grinned Iain the burly ferryman as he swung my collapsible bicycle into his boat at Tayinloan, where shelducks floated in the aquarium-green water. It was a dream day to be crossing, with the Paps of Jura grey-blue beyond the near greenery of rocky Gigha. We paused to look to port and starboard at great northern divers.

“There’s still plenty of them about, but they’ll be off to Iceland any day now, I expect,” said Iain as we admired their sculptural beauty, ebony black on the head, snowy white on the breast, and ornamented on the neck with a little window of zebra striping. I had not noticed until now how steeply the brow of this bird rises from the stout, pointed bill. Nestlings of this diver have been seen in Wester Ross, which is exciting news for bird enthusiasts.

The ferry across the Sound of Gigha takes less than half an hour

The ferry across the three miles of the Sound of Gigha takes less than half an hour, and on the other side, awaiting us with the car, was Mrs McSporran to help us up with our luggage. Service indeed, and tea was on the go within minutes of arriving.

Mrs Mac not only runs the shop and post office with her husband, but accommodates visitors handsomely. Great now to head north along the single-track road for Tarbert, my favourite bit of the island.

Gigha has six miles of tarred road serving the eastern side where most of its 180 inhabitants live. Ardminish, where the ferry lands, is conveniently midway, with church, hotel, shop and principal centre of habitation within short distance. Northward my run began with a free-wheel through a riot of flowers on the roadside verges, blooms of spring and summer being incredibly mixed up: bluebells, marsh marigolds, primroses, stitchworts, germander speedwell, herb Robert, red campion, celandines and cuckoo pint.

Only Gigha can produce so much in such little space

From the whins and roses came jangled songs of whitethroats, sedge warblers, whinchats, wheatears, wrens and yellow hammers. A buzzard mewed overhead, snipe zig-zagged from a ditch, oyster-catchers shrilled and peewits cried. Only Gigha can produce so much in such little space.

At the Narrows of Tarbert I drew to a stop at the sight of three farm tractors working in a single large field, one of them harrowing, one dragging a roller, and the third seeding barley. “Aye, everything’s behind because the ground was so wet,” said one of the men. “But it’s fine now. I’d say we get as good a return from this land as from anywhere in Scotland. I was at Stranraer before coming here, and that’s pretty good. But this is better!”

I asked about the piles of enormous boulders at the edges of the fields. “Yes, we’ve got a JCB digger on the island to clean the fields and make them easier for machinery. We’ll use a combine harvester to clear this field. The new laird, Mr Landale, is making a lot of improvements to the farms, putting in milking parlours and modernising the buildings.” The eleven farms on Gigha are tenant farms. Only one house on the island is not owned by the laird, I was told.

Seated on a pinnacle, I felt the world was mine

Leaving my bike, I pushed across the neck to the rocky coast to enjoy the last hour of sunset over West Tarbert Bay. The sea had an oily calm, echoing the golds and reds of the clouds. Seated on a pinnacle, I felt the world was mine. Even the gullery was quiet. Eiders and mergansers were silhouettes, and a gannet sailing round the bay suddenly went down with a splash in a 40-foot dive.

I was anxious to hear the news of Gigha since the death of Sir James Horlick, who did so much for the island. Mine host, Seumas McSporran, was the perfect man to give me it, combining, as he does, the role of postmaster, shopkeeper, petrol-pump attendant, rent collector, undertaker, registrar and partner in the guest-house.

He told me about the new owner, Mr David Landale, whose other estate is at Dalswinton, Dumfries, where he lives most of the time.

“We’re very lucky to have a man like him. He’s putting money into the place, as you’ve seen in the farms and fields. He’s made a great job of the hotel, too, putting in extra bedrooms and modernising it. And this summer the creamery is being altered to put in a whey-butter plant, which will give employment to another two girls.”

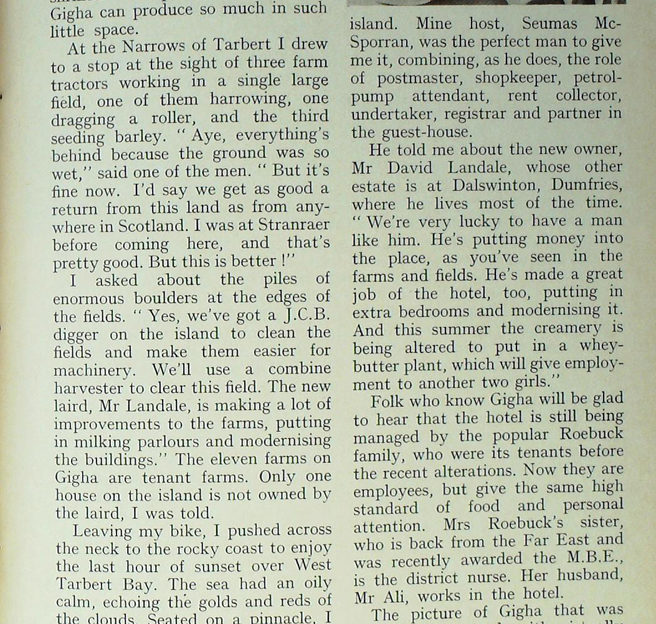

Folk who know Gigha will be glad to hear that the hotel is still being managed bv the popular Roebuck family, who were its tenants before the recent alterations. Now they are employees, but give the same high standard of food and personal attention. Mrs Roebuck’s sister, who is back from the Far East and was recently awarded the MBE, is the district nurse. Her husband, Mr Ali, works in the hotel.

Children will always have to go away since a small island can produce only so many jobs

The picture of Gigha that was emerging was good, with virtually no unemployment, though children will always have to go away since a small island can produce only so many jobs. On Gigha the population is healthy, with fifty children to 130 adults. Its strength is in its good soil for producing crops and early pasture. The dairy herds keep the creamery going, three boats fish full-time, and the big house employs seven in its famous garden.

On Sunday afternoon I had the unexpected pleasure of taking a walk with one of the farmers, John MacDonald of Druimyeon More. It happened when he took me to see a buzzard’s nest. “I’ve never seen one so low down,” he told me. “If we go quietly we’ll probably see it fly off the eggs.”

Just a yard below our feet was the grass cup of the nest with three large, whitish eggs

We did. I clicked the camera, but the bird shot off the nest so fast that I’ll be surprised if I get more than a blur on the negative. Just a yard below our feet was the grass cup of the nest with three large, whitish eggs. From below, the pile of large sticks below the rock was inconspicuous.

Afterwards, Mr MacDonald said, “If you wait until I finish in the byre I’ll take you to a stone with an interesting story attached to it. There was a boy called Alexander McCallum who was herding cattle about a hundred years ago when he saw a sailing ship. It looked so nice he drew a likeness of it with the point of his knife. He went away to the fishing shortly afterwards. He would be about sixteen when he made the drawing, and he had told folk on the island about the ship. Years afterwards he was drowned in the Pentland Firth and his body was identified because of the tattoo of a sailing ship on his arm – the same as the one he had drawn with his knife on the rock on Gigha. The story was handed down, but it was only 30 or 40 years ago that the drawing on the rock was rediscovered.”

Half an hour later we were off up the wee road that leads to Mill Cottage, whose loch powered the water-wheel used for grinding the island corn. “Yes,” he said, “this was once a busy place. My grandfather and grandmother went to live in the township here after they got married about 1880. There were seventeen families neighbouring them. Now there’s nobody. My brother and I farm the ground, and it’s some of the best on Gigha. One day when I was singling turnips I found an old brass badge in the ground. It had the date 1798 on it, and the words, ‘Armed Association’. Nobody has ever been able to tell me what it meant.”

On the ridge above we found the stone slab with the outline of the ship clearly visible

The only lochs on Gigha are on this remote west side, south of Ardaily, grand grazing ground, scattered with munching cows and playful calves. Up there we fell in with a couple of island families and their children enjoying the breeze. They had walked over from Ardminish. On the ridge above we found the stone slab with the outline of the ship clearly visible, despite a fur of lichen and some disfiguring graffiti.

John was enjoying himself. “How would you like to see a big cave now?” he asked me. “It goes right into the hillside at the back of a gully with big cliffs.” So off we went, and it was as he said, but the highlight for me was the peregrine falcon which went dashing out beneath us towards Jura and then came winging back over us in a great arc, the epitome of power and strength.

“The summer here is great,” said John MacDonald. “You can look forward to so much – the crops growing and the harvest. If I could get away I would like to see the farms in other parts of Scotland. I’ve a notion for the Black Isle. They say they’re very good up there. But we’re always too busy here, except in the winter when nobody wants to travel. I just stay at home and play the accordion. My brother plays it, too.” The pair of them run the farm, and sister Sarah who keeps house gave us welcome cups of tea.

Though it’s a small island, there is so much to see and do on it

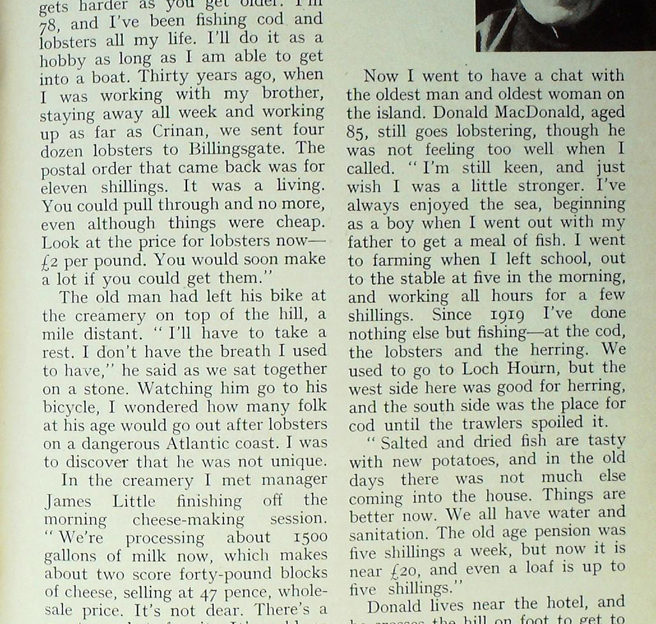

Visitors who come to Gigha say that the days are always too short for them, because though it’s a small island, there is so much to see and do on it. That day with John had been a long one for my wife and myself, beginning in the morning with the round of Garbh Eilein – the rough island – well named if not strictly true, since you can walk to it on a strip of silver sand dividing two enchanting curves of bay. The best way to traverse the island is clockwise, keeping low on the rocks of the seashore to avoid the brambles tangling the upper tiers. Soon, if you persist past a bad bit, you are amongst the tysties – the black guillemots – which nest deep down among the boulders. It was a colourful place, with yellow lichen and sprays of seapinks against the red granite. It was dazzling that day, and from high perches we could look down on the black and white guillemots paddling their red legs, or forming little committee meetings and showing carmine throats as they whistled musical remarks with jerking necks.

The herring and lesser black-backed gulls were being remarkably restrained despite the fact that we were constantly side-stepping nests containing two or three eggs. High above us we could see two islandmen collecting a few dozen eggs as food for their calves – an old custom on Gigha. Undoubtedly the gulls would have been a lot more clamorous if there had been fluffy young about. We were ready for our beds that night after twelve hours on the go.

A swan with six eggs allowed me a peep as she floated serenely above her reflection

Next morning was even more blissful, hardly any wind, and the air fragrant with the scent of whins in yellow drifts all over the island. Up past the kirk I crossed the stile giving access to the ridge, and dropped down the other side to Eun Eilean where a swan with six eggs allowed me a peep as she floated serenely above her reflection.

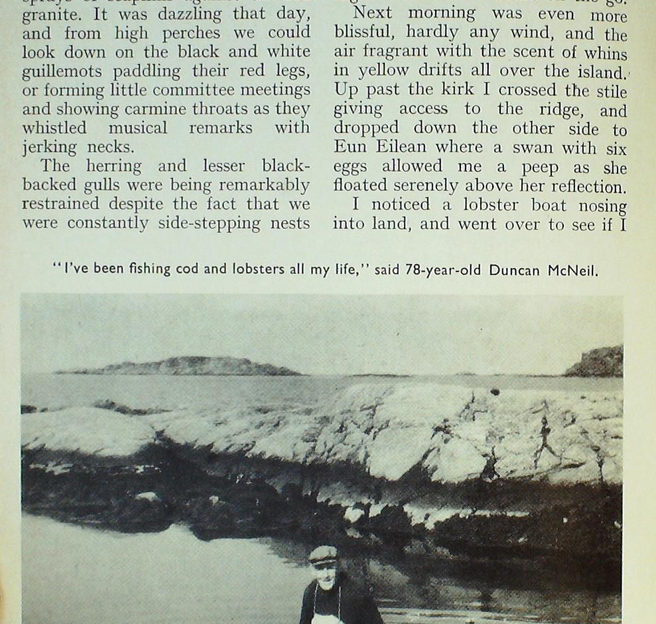

I noticed a lobster boat nosing into land, and went over to see if I could be useful with the landing.

“I only got one lobster. They’re no very plentiful,” said Duncan McNeil as he handed me out his box and undid the outboard motor for me to carry up to his wee hut. “It gets harder as you get older. I’m 78, and I’ve been fishing cod and lobsters all my life. I’ll do it as a hobby as long as I am able to get into a boat. Thirty years ago, when I was working with my brother, staying away all week and working up as far as Crinan, we sent four dozen lobsters to Billingsgate. The postal order that came back was for eleven shillings. It was a living. You could pull through and no more, even although things were cheap. Look at the price for lobsters now – £2 per pound. You would soon make a lot if you could get them.”

I wondered how many folk at his age would go out after lobsters on a dangerous Atlantic coast

The old man had left his bike at the creamery on top of the hill, a mile distant. “I’ll have to take a rest. I don’t have the breath I used to have,” he said as we sat together on a stone. Watching him go to his bicycle, I wondered how many folk at his age would go out after lobsters on a dangerous Atlantic coast. I was to discover that lie was not unique.

In the creamery I met manager James Little finishing off the morning cheese-making session. “We’re processing about 1500 gallons of milk now, which makes about two score forty-pound blocks of cheese, selling at 47 pence, wholesale price. It’s not dear. There’s a great market for it. It’s sold as island cheese, but we want to build up a name of our own and sell it as Gigha cheese.”

Hours of work for James are 5am until 3pm, with two days off a week. Another cheese-maker comes on as James goes off. The work-force in the creamery stands at four at the moment.

“I’m still keen, and just wish I was a little stronger”

Now I went to have a chat with the oldest man and oldest woman on the island. Donald MacDonald, aged 85, still goes lobstering, though he was not feeling too well when I called. “I’m still keen, and just wish I was a little stronger. I’ve always enjoyed the sea, beginning as a boy when I went out with my father to get a meal of fish. I went to farming when I left school, out to the stable at five in the morning, and working all hours for a few shillings. Since 1919 I’ve done nothing else but fishing – at the cod, the lobsters and the herring. We used to go to Loch Hourn, but the west side here was good for herring, and the south side was the place for cod until the trawlers spoiled it.

“Salted and dried fish are tasty with new potatoes, and in the old days there was not much else coming into the house. Things are better now. We all have water and sanitation. The old age pension was five shillings a week, but now it is near £20, and even a loaf is up to five shillings.”

Donald lives near the hotel, and he crosses the hill on foot to get to his fishing on the other side.

Mrs Catherine Wilkieson lives near the post office and is in her 90th year. I asked her if she could remember when the farmers took their corn to the mill.

“Yes, I saw the corn in the kiln being roasted, and the farmers turning it with rakes. I tasted the porridge made from the meal, but the mill stopped working before the First World War. There was never any poverty on Gigha. There was always fish and potatoes and whelks from the shore. There was more Gaelic spoken than English. We had the post office and shop, and islanders came in who hardly knew any English.”

I was interested in the fishing methods of that time. “It was done in wee boats with a sail and jib, mostly round the island, but they would go up north to the herrings. There were 400 on the island 80 years ago when the census was taken, and the school roll was from 60 to 80. My mother had been children’s nurse to Mr Scarlett, who owned Gigha before Sir James Horlick bought it. Mr Scarlett made a nice garden, but it was small compared to the 50 acres it is now.”

It’s a feast of colour, with shrubs and trees of every size and hue

My favourite way of entering the famous Achamore gardens is by descent from the bare top of the hill, so that the scents of pines and flowers waft up to meet you. It’s a feast of colour, with shrubs and trees of every size and hue – yellow, white, pink, red, mauve – in a spacious setting that gives the feeling of wild naturalness. Arcady indeed, even to peacocks strutting the lawns and birds singing everywhere. And it’s all thanks to the vision and horticultural skill of a quarter of a century ago. Col Horlick has left the plants in the care of The National Trust for Scotland, with an endowment to perpetuate his work. Tribute, too, should be paid to William James York Scarlett for planting the sheltering trees that made the garden possible. They date back to 80 years.

Emerging from the garden, I crossed the road and took the track across meadowlands that led to the shore and the white cottage that is the oldest inhabited house on Gigha. There, on the white, sandy beach, I met Vi Tulloch, who happened to be out looking for me. Mrs Tulloch is a sculptress, who, from chunks of wood, produces superb art forms such as the swimming whale in the foyer of Colonsay Hotel. This wonderfully life-like representation was carved from a single piece of bog oak. Her art is futuristic – movingly beautiful – and expresses concern for creatures under pressure from man.

Soon we were sitting down to a cooling beer and bread and cheese

It was hard to believe that this slim, lively woman, so full of vigour, is a grannie who has been sculpting on Gigha for over a decade. But her grandchild was there in the cot as proof, as were her tall son and young daughter-in-law on holiday from Kilmarnock. Soon we were sitting down to a cooling beer and bread and cheese, while Vi showed us photographs of her recent exhibition work, and two of her “pieces.”

We talked about the otters which she sees in the bays near the house. One hanging up in a tree was found dead in a lobster pot by a fisherman. Its skeleton will tell her much about its anatomy, and from memory she has enchanting glimpses to call upon of three otter cubs playing with Mother. Vi works mostly outside on her sculpture, and from her snug corner out of the wind gets views of hen harriers quartering, and has seen a merlin take one of the garden birds before her nose.

It was with reluctance that I had to forego the pleasure of hearing more, for the ferryboat was due to leave at 6pm on the last run of the day. It was a rush, but we made it, and were back in our home on Lomondside before 10pm, feeling there was very little wrong with the world.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday!

- Tom heads over the Sound of Gigha

- Mr & Mrs James McSporran look after him well

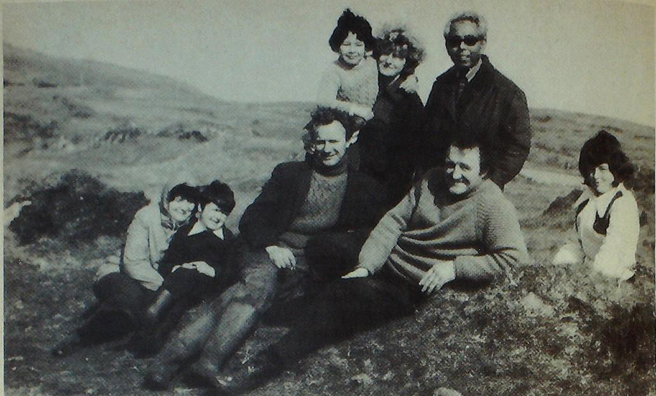

- Seated left is John MacDonald and behind him Mrs Ali with her husband and son

- Cheeses at Gigha creamery

- 78-year-old Duncan McNeil

- Gigha’s oldest man, Donald MacDonald

- Very little wrong with the world

- A group of Gigha islanders

More From Tom…

Two years’ worth of Tom’s columns for our magazine are now available online.

Click here to find another great read to find out how much (and at the same time how little) has changed in 50 years.