Jackie Stewart | Flying Scotsman

Few people really deserve the title “legend”. But if anyone does, it’s three-times Formula One ace Sir Jackie Stewart.

Moments like this don’t come along every day. To remind a motorsport legend of a milestone in his career is something that would make any Formula 1 aficionado incredibly happy. And it did.

When we speak, Sir Jackie Stewart is at home in Buckinghamshire. It’s July – the day before the German Grand Prix and one of the few days in the 75-year-old’s calendar that he has time to talk.

When asked if he’s heading over to the Nurburgring to see the race he won on three occasions and the place where he was first to the chequered flag for the final time before retiring 40 years ago, he is taken aback.

“Quite right. I hadn’t thought about that – so it is. No, I’m not going. I’m going to watch the Wimbledon final,” he laughs.

We know that one turned out well.

It’s not that Sir Jackie has forgotten. He’s as sharp as ever, it’s just that he has his terrier-like determination sunk into a new race – to help those who, like him, have dyslexia.

“I was the dummy in the class,” he says. “I was identified as being stupid and thick – and they were right! In educational terms, I was incapable of doing what the other children were doing. That was in primary and secondary schools.”

There were 54 children in Sir Jackie’s class at Hartfield Primary School in Dumbuck, Dunbartonshire (since renamed Milton). The law of averages means he was one of a few children who had learning difficulties.

“By my teacher’s reckoning, there were four or five dummies. That moves from the classroom to the playground, where the clever folk don’t want to talk to the dummies.”

His outlet was sport

Sir Jackie believes that dyslexia is a disability and like all people with disabilities, dyslexics need to find different and new ways to do things. When they have a different outlet they can excel – and his outlet was sport.

“I was quite good at football. I played for the school at county level a couple of times, but that was simply burning off energy, I would run for the ball, go in for the tackle. I was trying to prove I could do something better than someone else.”

However, it was shooting that first lifted the confidence of a young Jackie Stewart.

“I grew up with a shotgun and a fishing rod in my hand”

“My grandfather was a gamekeeper at Eaglesham (on Lord Weir’s Estate). That’s where both my parents were from. So I grew up with a shotgun and a fishing rod in my hand.”

His dad started him shooting at the age of 14. He was a small teenager, in weight and height, but was a natural.

“My grandfather, father and brother were all good shots so it may have been in the genes. I won the major award at my first shooting competition. I think my life opened up that day. For once I was good at something – and this was a competition for all ages. I was proud of something that I did.

“It can be difficult for a young dyslexic to find the thing they are good at. Sport saved me,” he says.

With no possibility of academic achievement Jackie began working in his dad’s garage. It still stands, with the family home next door, complete with blue plaque. He found a way to put another talent to use there.

“I have immense attention to detail. Everything needs to be clean. I have always been like that. That meant that our garage was different from every other garage. This was something else I could be proud of.”

He was also proud of his brother Jimmy, older by eight years, who was making a name for himself in motorsport. Their father, Bob, had bought Jimmy a car to race in the Ecurie Ecosse team and he progressed to the highest levels, even competing in the 1953 British Grand Prix, where he was up to sixth before spinning off in bad weather.

“So I was going to races with him with my autograph book, which I still have. That was my reason to be interested, but I never thought I would be able to do it. I was happy with my shooting and working as a mechanic in the garage.”

That all changed when a customer of Bob Stewart’s garage, Barry Filer, gave the young mechanic an opportunity to drive one of his cars as a reward for keeping them so well.

Filer asked if Jackie “wanted a wee run down at Heathfield in Ayrshire”. That was in a Porsche, but he subsequently went on to also drive his Marcus and Aston Martin.

“I won a lot of races for them”

“David Murray at Ecurie Ecosse then saw me and I raced for them, including down south, where I won a lot of races for them.”

It was “down south” that he met Ken Tyrrell in 1964, and that was the perfect partnership, which lasted for the remainder of his driving career.

That was a career of three World Championships in 1969, 1971 and 1973. There were 27 wins, 43 podiums and 17 pole positions – so he was a racer, he didn’t get to pole and simply manage to stay ahead.

His career was filled with great victories but some of the most awe-inspiring drives were some that he didn’t win. In 1967, during the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, he was forced to drive the whole race one-handed as the other kept the car in gear. He finished a close second.

“During that five years when I was at the top of my career, there was a two out of three chance that you would be killed. That’s ridiculous. The organisers, the track owners, the governing body – none of them wanted to do anything about it. If I had not been a World Champion, I wouldn’t have had the voice in terms of getting access to the people that mattered. I also wouldn’t have had the power of the media behind me to show the reality of the situation.”

That was the turning point

As we talk, Sir Jackie recalls that it is over 20 years since the life of a Formula 1 driver was last lost at a race – Ayrton Senna at San Marino. That was the second death that weekend, following Roland Ratzenberger’s death in qualifying. And that was the turning point.

“Motor racing is dangerous – it says so on the tickets. People are there to watch something that they themselves would not dare to do. They would like to do it, though.

“The changes in safety is the thing that I’m most proud of achieving in the sport. It was obviously great to be a World Champion and to win the amount of Grands Prix that I did, but since that day we haven’t lost a life in practice, qualifying or racing.

“Sometimes there are windows in our life where we can just step in and help.”

That’s equally true of his current passion – one that has brought him closer to home. “I tried at Westminster first, but got so fed up of the ridiculous bureaucracy I couldn’t handle it any longer. However, Professor Duncan Rice, the Aberdeen University Principal and Vice-Chancellor saw me speak about the issues of dyslexia, learning disabilities and learning difficulties at an event in Gleneagles and was interested.”

First Minister at the time, Jack McConnell, allocated £1.4m to establish a Chair of Inclusive Studies at Aberdeen, which would train teachers to work with those struggling with learning.

Now President of Dyslexia Scotland, Sir Jackie believes that although some inroads are being made, the excellent schools are still in the minority and there is still much work to do.

“I believe that the work I’m doing now is probably the most important thing I’ve done for Scotland. Of course, I’ve driven racing cars and being Scottish I’ve promoted the country by having the Stewart tartan around my helmet. That gave Scotland a presence on a global basis.

“But this work on improving the educational conditions for dyslexics – that will change lives.”

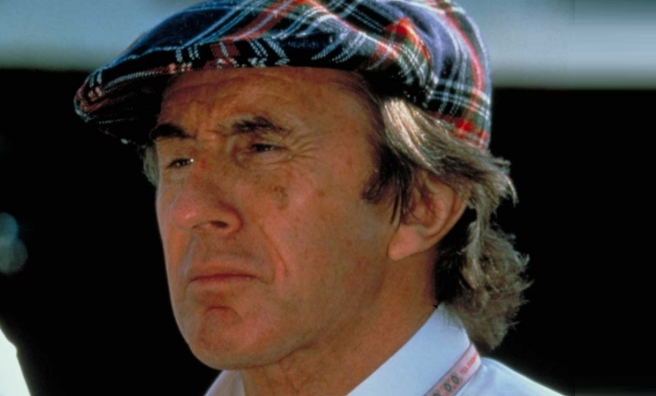

- A thoughtful Jackie Stewart (Pic: Getty Images)

- Jackie Stewart won the German Grand Prix at Nuerburgring racing circuit, Aug. 1, 1971 (Pic: Press Association)

- Sir Jackie, a proud Scot

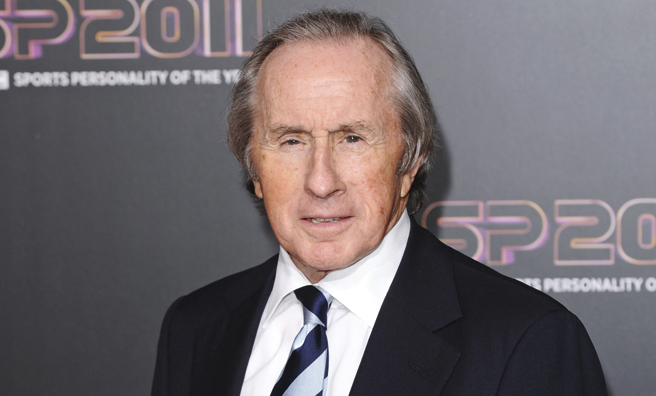

- At the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Awards (Pic: Rex Features)

About Jackie

- Sir Jackie lives in Buckinghamshire

- He is now President of Dyslexia Scotland

- He won 3 World Championships – 1969, 1971 and 1973

- In his career he had 27 wins, 43 podiums and 17 pole positions