Sir Alexander Ogston

Sir Alexander Ogston was the clean freak who discovered a killer strain of bacteria

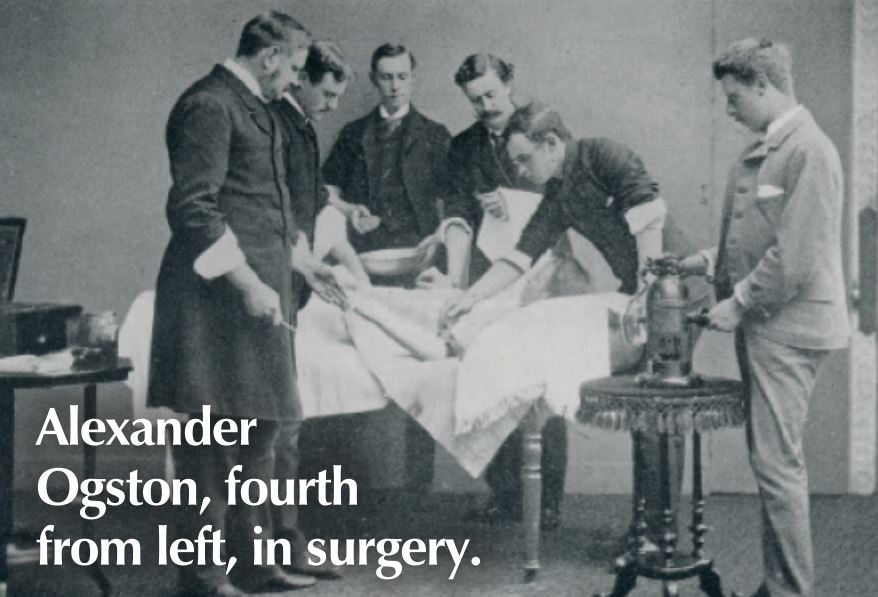

BY the late 19th century, Aberdonian surgeon and professor Alexander Ogston had earned himself quite a reputation as a man who liked everything in his lab to be meticulously clean.

His students at the city’s university were so amused by his incessant disinfecting, they composed a song about it:

The spray, the spray, the antiseptic spray,

A.O. would shower it morning, night and day,

For every sort of scratch,

Where others would attach,

A sticking plaster patch,

He gave the spray

Ogston’s spray was a bit more heavy duty than cleaning sprays we’d use in the kitchen today – he used carbolic acid, introduced to him by its pioneer, Joseph Lister.

By bringing it to Aberdeen’s surgical theatres, Ogston saved countless lives at a time when even the most minor post-operative infection could kill.

Not content with simply fighting those nasty germs, Ogston also wanted to work out what they were, in order to prevent wound infection.

He secured a grant of £50 from the British Medical Association (BMA) to buy a microscope and turned his garden shed into a laboratory.

Examining samples of – skip this part if you’re eating – pus from a patient’s abscess he was rewarded with “beautiful tangles, tufts and chains of round organisms in great numbers”.

In 1880 Ogston was ready to share his findings – a hitherto unidentified bacterium he named Staphylococcus (of which MRSA is the most familiar modern-day strain).

Despite his thorough research, Ogston had a problem convincing the medical community that his discovery was the real deal.

The Aberdeen branch of the BMA was sceptical – the Editor of the British Medical Journal dismissed his claims and asked, rather rudely, “Can anything good come out of Aberdeen?”

With little support in his home country – even Lister, the king of antiseptic himself, struggled to accept his scientific evidence at first – Ogston decided to present at a surgical congress in Berlin and was made a fellow of the German Surgical Society as a result.

He then published an in-depth report in the BMJ the following year and slowly gained recognition for having discovered something tremendously important.