Marjory Fleming

A-Z Of Great Scots

« Previous Post- Christian Fletcher

- Helen Duncan

- Ebenezer MacRae

- Marjory Fleming

- Sir Alexander Glen

- Wyndham Halswelle

- Isabella Elder

Marjory Fleming was a literary prodigy – and could have been so much more…

Marjory Fleming was a literary prodigy – and could have been so much more…

FIFE girl Marjory Fleming wrote her life’s work – a bounty of literary delights that came to be admired by the likes of Robert Louis Stevenson and Mark Twain – before her ninth birthday.

Born in Kirkcaldy in 1803, Marjory was taught by her mother before moving to Edinburgh aged six to be tutored by her cousin Isabella Keith.

A voracious reader, she enjoyed the works of Alexander Pope, Ann Radcliffe and Sir Walter Scott – a family friend or even a distant relative, depending on which account you believe.

Life cut short

Marjory began writing poems, letters and a journal while being taught by Isabella – a charming, witty snapshot of a middle-class Scottish childhood. Encouraged by her cousin, it became clear this was a girl with incredible talent. But hers was, sadly, a very short writing career.

Marjory returned home to Kirkcaldy, aged eight, and she missed Isabella terribly. Writing to her cousin in September 1811, she told her, “We are surrounded with measles at present on every side.”

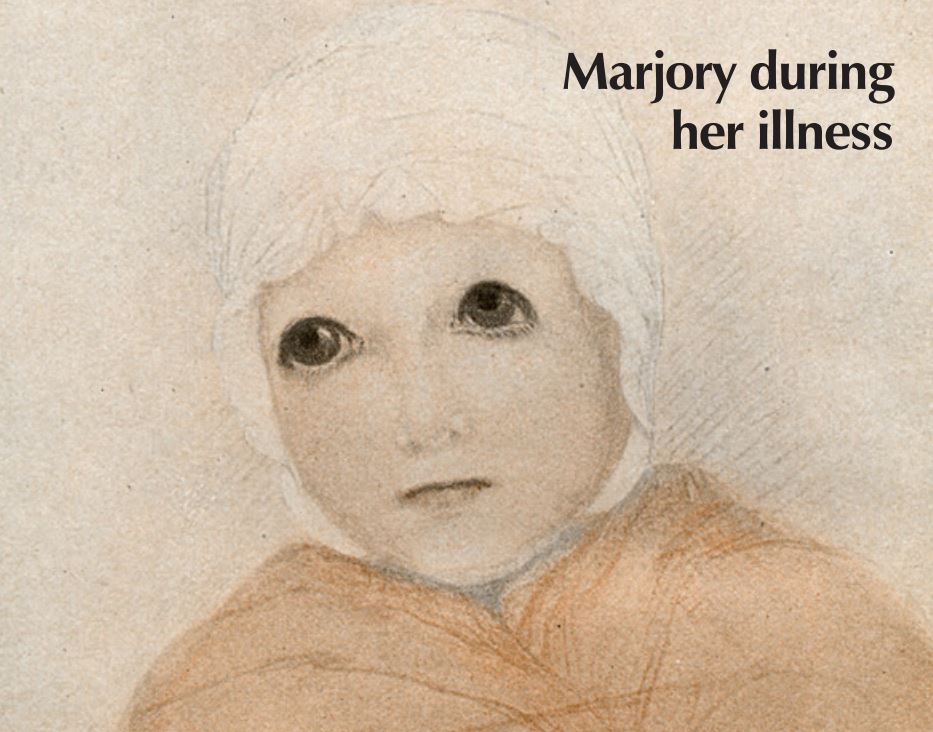

In November, she succumbed to the disease. She seemed to recover but, in December, a month before turning nine, she died of meningitis.

The journal she kept in the last 18 months of her life remained unpublished for 50 years, until a journalist printed excerpts in The Fife Herald. These vivid, delightful snippets, along with the account of her short but brilliant life, captured the public imagination and she was widely read in Victorian times.

Many early editions of her work were, in parts, heavily rewritten as editors thought some of the language Marjory used was inappropriate for an eight-year-old girl. She acquired a nickname, Pet Marjory, which stuck and is still used today.

Many early editions of her work were, in parts, heavily rewritten as editors thought some of the language Marjory used was inappropriate for an eight-year-old girl. She acquired a nickname, Pet Marjory, which stuck and is still used today.

In a 1934 edition, Robert Louis Stevenson is quoted on the dust jacket, “Marjory Fleming was possibly – no, I take back possibly – she was one of the noblest works of God.” Mark Twain described her as being “made out of thunderstorms and sunshine”, and Virginia Woolf’s father Leslie Stephen, in 1898’s Dictionary Of National Biography, claimed that “no more fascinating infantile author has ever appeared”.

Marjory’s manuscripts in the National Library Of Scotland are a captivating but bittersweet portrait of an extraordinarily clever, endearing and sometimes quite naughty girl, destined for great things had her life not been cut so cruelly short.

Discover more about the remarkable men and women who shaped Scotland and changed the world with our new bookazine Scottish Heroes

Available online from DC Thomson Shop or in stores at WHSmith