Scottish History In Minutes – The Life Of Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, the Scottish historical novelist, poet, playwright, and historian whose works remain classics…

At 200 feet, the Scott Monument in Edinburgh – built in honour of Sir Walter Scott – is the tallest dedicated to a writer on the planet. Climb its 287 steps and you can gaze across that iconic capital skyline to Waverley station, which by public demand was named after Scott’s first novel. It’s the only train station in the world to be named after a book.

This A-lister level of adoration might initially seem a bit baffling. These days, Scott is far less celebrated than his contemporary, Robert Burns. But no author has been as critically acclaimed and commercially successful.

Poet, playwright, lawyer, novelist and ballad-collector, Scott was Auld Reekie’s Renaissance man and his influences stretch far and wide. In his lifetime, he became the first literary superstar and he left a remarkable legacy. Credited with being the creator of the modern historical novel, his idea of inserting fictional characters into recent history in classic novels such as Waverley, Ivanhoe and Rob Roy was an instant hit.

Waverley sold out its first edition of 1,000 copies in only two days. It went on to sell more than all the other novels sold in the UK in 1814 put together! Scott gave respectability to the reading of novels that had previously been sadly lacking. Great writers who followed such as Dickens and Tolstoy have acknowledged his influence on modern fiction. Scott continues to inspire.

Both Game of Thrones creator, George RR Martin and Outlander author, Diane Gabaldon are huge fans of his work. Scott’s success is made all the more remarkable by the fact that he only took up fiction writing in 1814 at the age of 42.

The Scott Monument in Edinburgh – a Victorian Gothic monument to Scottish author Sir Walter Scott. Credit: Shutterstock.

How it all began

His first love had been poetry. Indeed, he was one of the best-read, best-reviewed and best-paid poets of the Romantic era. He was offered – and declined -the role of Poet Laureate and only decided to turn to prose when he found himself being slightly eclipsed by the “mad, bad and dangerous to know” Lord Byron.

When Scott died in 1832, having written 28 best-selling books known collectively as the Waverley Novels, he was the most famous novelist the world had ever known. Yet, remarkably, the identity of the author of these works remained a mystery for 13 years.

Scott finally outed himself as the man behind them in 1827 to huge applause at a fund-raising dinner in Edinburgh’s Assembly Rooms. Switching from poetry to prose was always going to be a bit of a gamble and was probably the initial reason for Scott’s secrecy.

However, he soon found that anonymity had its advantages. Rumours were flying about the identity of the author people were calling, The Great Unknown. It created a book buzz that was extremely beneficial to sales. Amongst his considerable talents, Scott may well have been an early practitioner of the publicity stunt!

Born on August 15 1771, in a small flat in College Wynd in Edinburgh’s Old Town, Scott’s father was a successful solicitor whilst his mother was the daughter of a Professor of Medicine. Although he had a more privileged upbringing than most, it was still far from easy.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), Scottish writer in his study at Abbotsford, surrounded by historical weapons, portraits, and statues related to the subjects of his novels. Credit: Shutterstock.

Six of his brothers and sisters died in infancy and he himself survived a bout of polio as a toddler that left him with a pronounced limp in his right leg for the rest of his life. To restore his health, he was sent for extended visits to his paternal grandparents’ farm at Sandyknowe in the Scottish Borders. Listening to his grandfather’s stories and learning to read with his beloved Auntie Jenny, Scott developed his lifelong love of Border history, dialect and folklore that would inspire much of his literary work.

Originally Scott had trained as a lawyer

Scott predictably followed in his father’s footsteps and qualified as a lawyer in 1792. The romance of the written word still fascinated him though, and he began writing himself at the age of 25. First translating works from German then moving on to writing his own poetry.

In addition to his growing literary fame, Scott maintained a successful career in law. By the 1820s, having been granted the title baronet and elected President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scott was almost certainly the most famous living Scotsman.

Somewhat fittingly, in 1822, Scott was asked to stage-manage King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh. Despite some controversy over the King’s choice of salmon pink tights and mini-kilt, the day was a roaring success.

Scott had made tartan trendy and the event created an unprecedented interest in kilts and Highland dress, turning them into the symbols of national identity that they remain to this day.

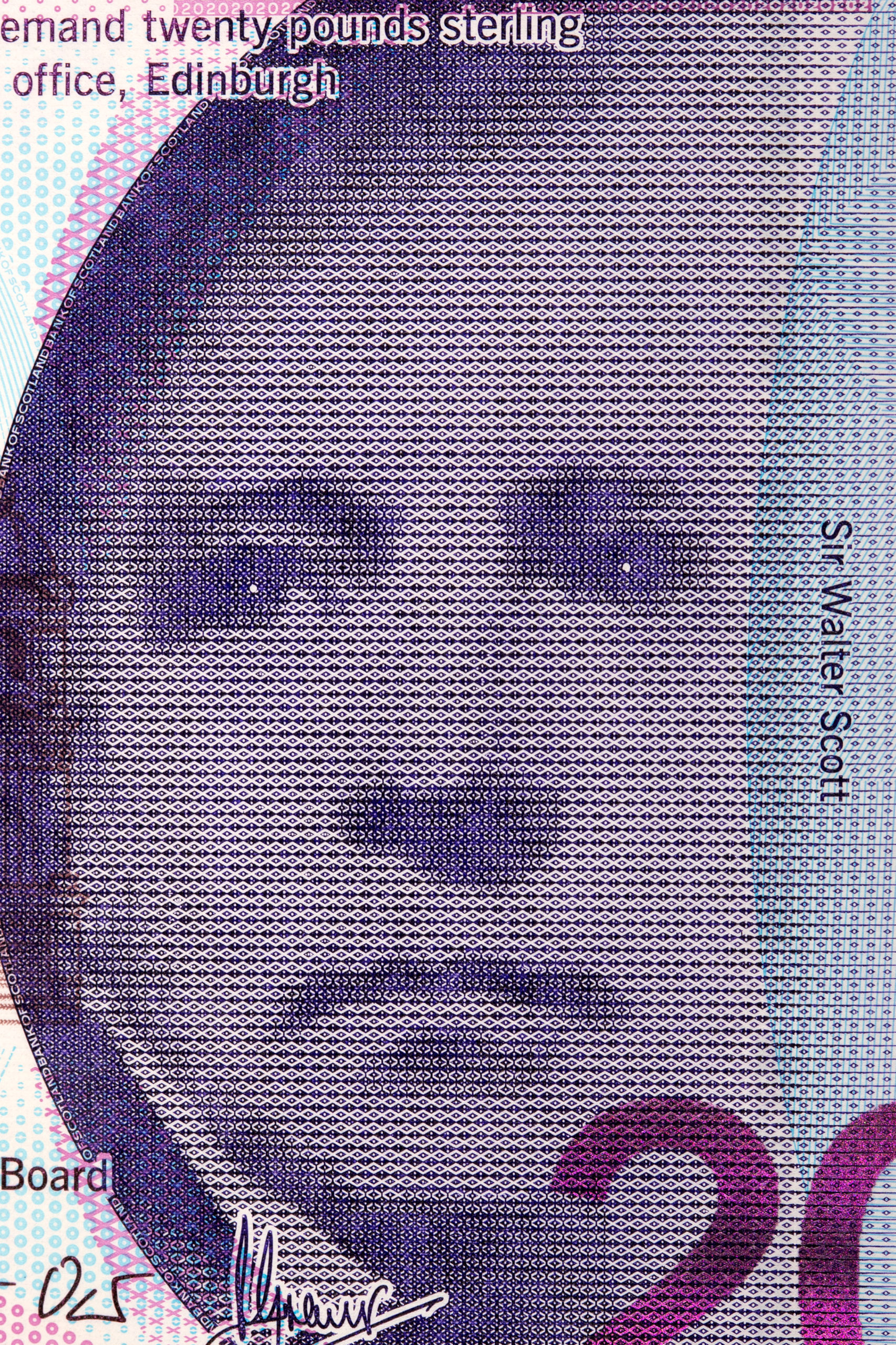

Sir Walter Scott’s face remains an important feature of the Scottish banknote today. Credit: Shutterstock.

It wasn’t Scott’s only contribution to patriotism. He’s also credited with saving the Scottish banknote. In 1826, Scott wrote a series of letters to the Edinburgh Weekly Journals under the pseudonym Malachi Malagrowther, championing Scottish banks retaining the right to print their own banknotes. The government was forced to back down and banknotes from the Bank of Scotland still bear a portrait of him in commemoration.

Scott wasn’t without his failings…

Somewhat ironically, Scott was never very adept at managing his own finances. In 1825, following the collapse of his publishing company he was left with considerable debts. Rather than declare bankruptcy, he proceeded to write his way out of trouble.

Scott continued to live at Abbotsford, the magnificent mansion he created near Melrose, until his death in 1832, aged 61, and was buried alongside his wife, Charlotte, at Dryburgh Abbey.

For the next half-century he was a national icon, as revered as Shakespeare. But during the 1880s Scott suddenly and dramatically lost his popularity. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Great Unknown had turned into the Great Unread.

Yet, Scott deserves our respect. He was the first writer to visualise history. To tell action-packed, swash-buckling stories that brought heroes to life in glorious technicolour.

He also introduced the word “glamour” into English literature. Its original meaning was a magical power capable of making ordinary people, dwellings and places seem like magnificent versions of themselves. What better way to describe this Scottish icon’s remarkable literary talent?