Glen Esk to John O’Groats Part Three

Part Three: Along the Waters of Unich

I could have done with a lot more of the gorge which ended suddenly on undulating moorland, the kind of country you don’t want to get lost in. Adam explained its topography.

“From where we are now we are as near to Milton of Clova as to where we left the car in Glen Esk. If we kept direction we would come out by Loch Brandy. You see those deer on the far skyline — Loch Muick is just over the other side. It looks very wild and remote, but it’s approached nowadays by Land-Rover tracks from Balmoral and Glen Lee, for deer stalking.”

Adam told me it was the best day he’d had on the hill for many weeks.

“The weather pattern has been that the day begins promising but breaks down by afternoon, or the other way round. It never settled for long enough to let you get right out to get on with your work on the high tops of the Cairngorms—very frustrating. In fact the dotterel did quite well, but I never did manage to check the snow buntings.”

The part we were in was particularly good for dunlin.

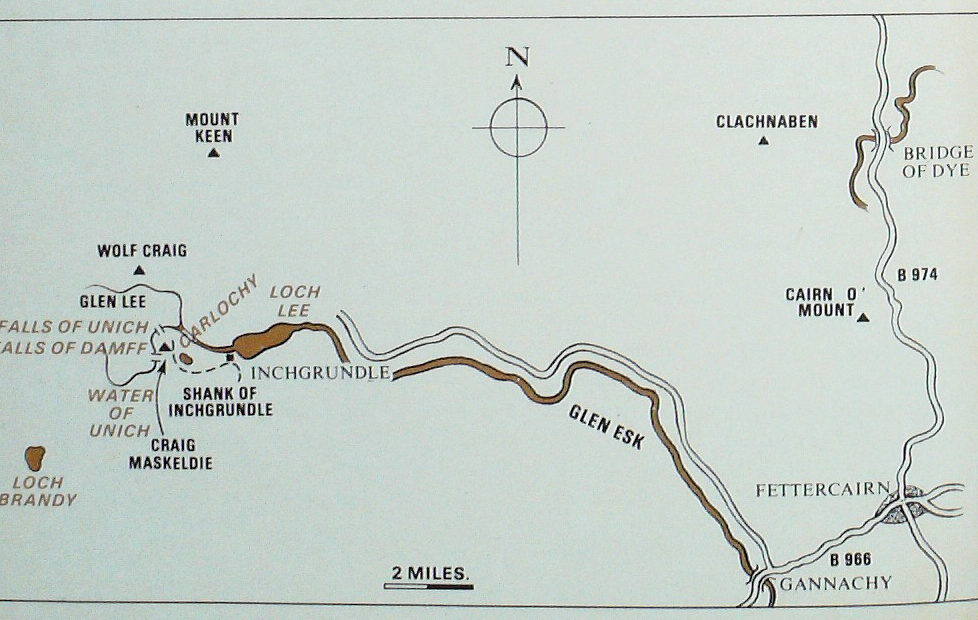

We swung east to come out on the corrie rim and look down the crags and tree-hung lower slopes of Craig Maskeldie to the dark oval of Carlochy, a saucer of water emptying into the main burn just short of Loch Lee.

All that remained now was to jog down the Shank of Inchgrundle, the word shank being the equivalent of ridge, now spanned by a bulldozed track from the keeper’s house at Inchgrundle.

On the way down Adam was telling me of some of the methods he uses now in his grouse research, the most revolutionary being a solar-powered transmitter. Tiny and gelling its energy from the sun, it is no embarrassment to the birds, whose “bleeps” lead the researcher to the bird brooding eggs on the nest or its whereabouts on the moor.

“We were puzzled last year when suddenly we were getting no signals at all from any of our transmitters. It was in the winter in a very bad weather period, but suddenly when we had a sunny day we heard them again. Only then did it dawn on us that the reason why they had gone dead was because there was not enough solar power in the dark days to work the transmitter.”

We talked about the marvellous spring with sunshine right through April and May, probably the best spell in living memory at that time of year, with record temperatures and an unusually early bursting of leaves and blossom.

In our part of the world I had noticed how tired and shrivelled the birches had looked as early as July. Adam came up with an explanation.

“The good weather not only brought the birches into leaf earlier than usual, but brought out the caterpillars as well. Normally, by the time the caterpillars arc hatched, the birch has manufactured in its leaf system a substance which resists caterpillar infestation. This year it didn’t have time.”

He thinks the birch will compensate next year by producing an exceptionally fine crop of leaves. He told me, too, that fieldfares were hanging around in flocks right into late May.

I envied him when he told me of some of the very fine ski tours he had done, over the Buck of Cabrach and other hills.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday

- The crags of the Shank of Inchgrundie in Glen Esk, seen from the Water of Unich.

More From Tom…

We have an extensive archive of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.