Glen Esk to John O’Groats Part Two

Part Two: Along the Waters of Unich

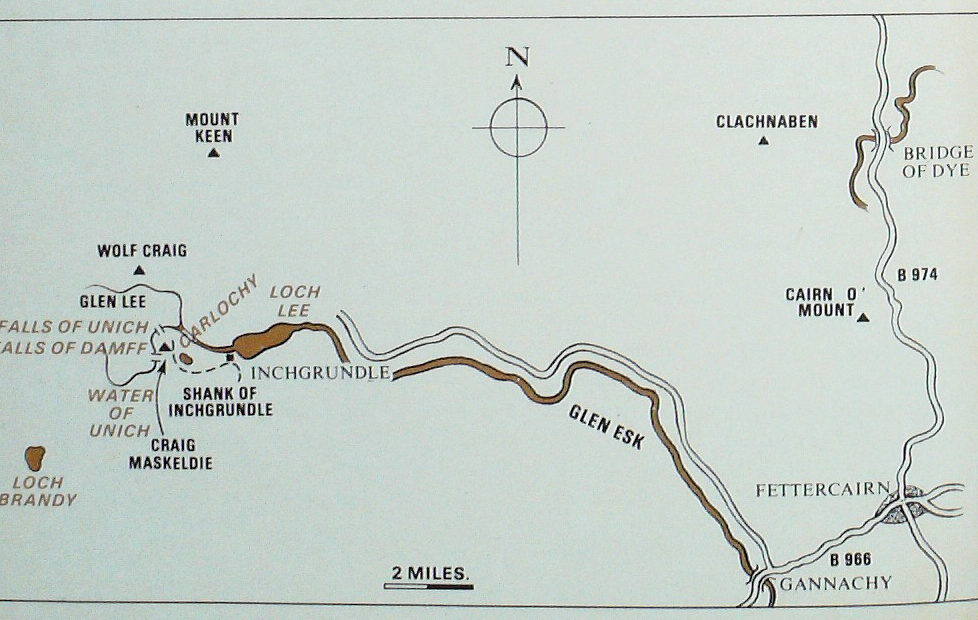

The favourite walk from Glen Esk is to Loch Lee.

In fact, I had never been beyond this point, so it was fine to walk the length of the loch to Glen Lee and, branching left, curve under the thrust of Craig Maskeldie.

While we looked up the rocky face hung with high-climbing birches we became aware of a miniature blizzard of specks like snowflakes, picked out by the sun against the dark face.

It was thistledown wafting upwards from a veritable crop of woolly seed-bearing heads on the flats under the craig. With binoculars we could follow them hundreds of feet into the air.

We followed the Water of Unich as it curved into an inner sanctuary between towering flanks. Above, the crags were in shadow, while the glen floor, speckled with sheep, had the brilliance of a bowling green.

All the time the waterfall was getting closer, and even from a distance we could see a haze of spray round its silver flash. As we drew nearer, I saw it was not just one fall, but a little staircase of them, ending in a final spout of about 30 feet down into a frothing pool.

Climbing up the rocks of its right flank I found myself in deep shadow, looking up at the blue sky through a dazzling rim of water curling into space, each falling droplet flashing like a diamond.

In ten minutes it had gone. The effect was due to the fact that I had been looking directly against the sun, so I had just been in time to witness one of the loveliest phenomena I have ever seen in the hills.

What made it all the better was the perfect point of rock a thousand feet beyond the fall, adding a final touch of drama.

This, Adam told me, is a great place for adders. Once he had encountered four in a single afternoon hereabouts.

“You’ll enjoy the next bit. up the rocky gorge to another waterfall as big as that one, the Falls of Damff.”

I certainly did for it was such an unexpected place, a deep cut enclosing the burn between steep walls with a path threading the locks.

“It was built as a pony track for deer stalking. Without it a horse could never manage up here. But it’s no longer used because there is a Land-Rover track on the other side of the hill.”

A grey wall flanked us vertically on the right and at eye level and above we could see it was a marvellous place for alpine flowers.

There were the green cushions of what had been moss campion, the faded grey-green leaves of purple saxifrage and the dried heads of yellow mountain saxifrage and many others. Hawkbit was still in bloom. It was certainly a place to return to in the lull flowering of early summer.

Soon we were looking down on the Falls of Damff, the lower plunge hidden from us by the birches which cling to the burn for most of its steepest course. Behind this now we could see the cone of Mount Keen (3077 ft.) rising beyond Wolfs Craig, and the path to the summit of Scotland’s most easterly Munro was clearly defined.

As we looked across to it a peregrine falcon flew across our line of sight and not far away rose a pair of ring ouzels, summer migrants still lingering in their breeding haunts.

Read the next Part Three online next Friday!

More From Tom…

We have an extensive archive of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.