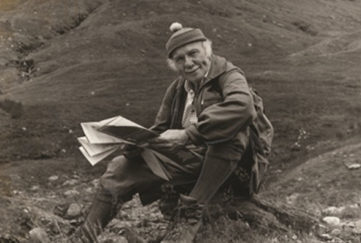

Fine Walks and Fine Weather

Despite a wet and windy forecast there was sunshine on the rusting bracken and a glow on the alders of the Glen Ample burn roaring among its gloomy “pots” in its last leap before emptying into Loch Earn.

We had talked about taking no more than a walk from these Falls of Edinample southward to the top of the bealach leading through to Loch Lubnaig, but the keen air had a freshening effect on my kilted friend Pat. Now he was talking about the corrie between Ben Vorlich and Stuc a’ Chroin and going up there if we could get across the swollen river.

It was easily done, for the bridge that was swept away had been replaced not far from the old one and we were soon making height on the contouring path rising round the hill for the first sight of Stuc a Chroin—”The Peak of the Cloven Foot” thrusting blackly against white clouds, as impressive as a Cuillin summit.

We were feeling the wind now as we struck up the ridge to Ben Vorlich with views to Ben Lawers and the Tarmachans opening up over the slit of Loch Earn.

Vorlich is supposed to take its name from Ard Mhurlaig. “A Promontory of the Bay”, which is also true of that other Ben Vorlich of Loch Lomond. Pat, a Gaelic enthusiast, was in his element, for the last time he had climbed these twin peaks was when he was a school boy 50 years ago.

At 3,000 feet the wind had us staggering as we followed the last narrows of its ridge to the top facing over the flat lands of the winding Forth with Stirling Castle and the Wallace Monument as landmarks. Eyes watering we plunged down against the wind for the col to find a perfect shelter among the rocks to eat our pieces and enjoy the setting.

Where Eagles Dare

While Pat took some photos I tried a rock scramble or two, but it was just too icy on the hands for comfort.

There was a great moment however. I had just grappled up a little overhang with Pat watching me, when whizzing low towards us came a bird, passing almost level with us wings half folded. As it swept across out went the aeroplane wings—a golden eagle, a young one, as we could tell by the white juvenile feathers on wings and tail.

How lovely it felt on the lower slopes of the hill, jogging down out of the wind with the warm glow of evening light on the hills.

The visibility was so good that the houses of Lochearnhead looked like newly washed pebbles under the grey rocks of Glen Ogle where we could see cars climbing up the white thread of the road to Glen Dochart.

“A hat trick,” I remarked to Pat, remembering that our last two excursions had been favoured by good weather in the face of bad forecasts.

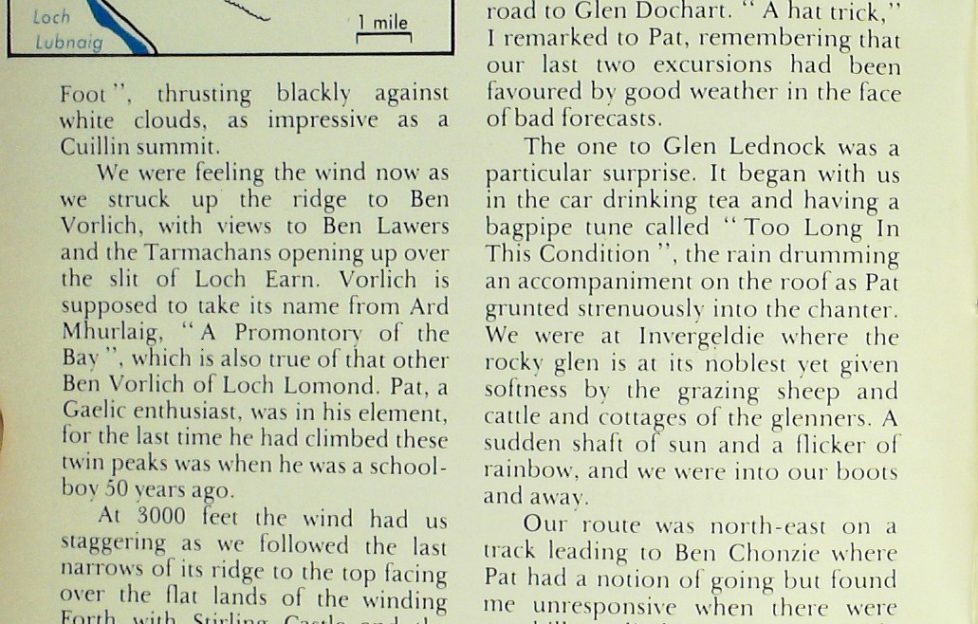

The one to Glen Lednock was a particular surprise. It began with us in the car drinking tea and having a bagpipe tune called “Too Long In This Condition”, the rain drumming an accompaniment on the roof as Pat grunted strenuously into the chanter.

We were at Invergeldie where the rocky glen is at its noblest yet given softness by the grazing sheep and cattle and cottages of the glenners. A sudden shaft of sun and a flicker of rainbow, and we were into our boots and away.

Our route was north-east on a track leading to Ben Chonzie where Pat had a notion of going but found me unresponsive when there were new hills to climb on the western side of the pass. Our route was along the rocky flank of Creag Tharsuinn climbing gently towards a neat little pass, at 2000 ft. a notch in heathery jaws.

We were looking forward to the view on the other side, into Glen Almond, but drew back from going too far when we saw a line of guns ahead of us barrels pointing in our direction above the butts. Then we noticed figures above us—a line of beaters.

Time to keep our heads down and wait for the crack of guns against risen grouse, but not many of them. The bitterly cold spring was a grouse killer at hatching time everywhere on Scottish moors.

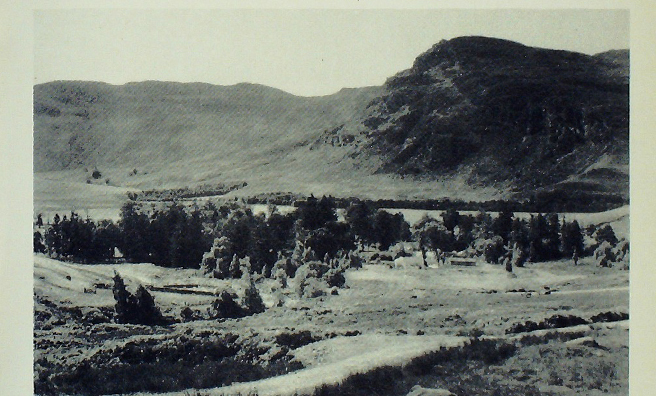

Area of Outstanding Scenic Beauty

From up there it would have been easy to descend and walk east to the Sma’ Glen less than ten miles away, or to Ardtalnaig on Loch Tay seven miles distant. Obliged to return to our parked car, we opted to stay on the tops, following a fine edge for two undulating miles then down a shoulder to regain the path.

The low sunlight was now at its most mellow, too good to turn for home just yet, so we swung across the hill-shoulder for a look at Spout Rollo where in pre-hydro-electric days the river used to cataract over rock slabs, and still does when Loch Lednock is overfull after heavy rain.

The enjoyment of that day was all the keener when rain drove us back to the car. It was no mere shower but a downpour blotting out the hills as we sped homeward. This part of Tayside Region, 3,000 hectares around Comrie and St Fillans, is one of the areas designated by the Countryside Commission for Scotland as of outstanding scenic beauty.

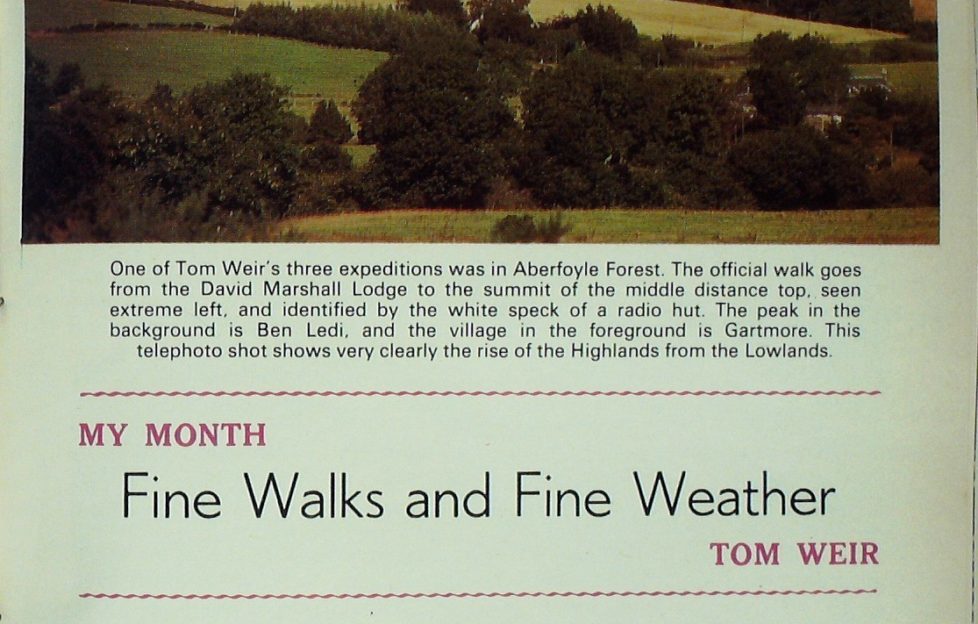

Then it was off to the Trossachs where we pulled some other good cards from the pack on a walk where I had never been, from the David Marshall Lodge above Aberfoyle to Lime Craig via “the waterfall”.

This is in the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park of course, approached by the Duke’s Road and Pat remembers paying one penny as a toll fee for his bicycle before the present road was built.

Now you buy a ticket from an automatic machine to park your car, though the use of the picnic lodge costs nothing in the summer months when it is open. Fine landscaping has been done here round the wee loch where the marked path leads off to the waterfall.

Not just a walk either but an educational stravaig, for by means of a series of neat information boards the story of the landscape and man’s use of it is told as you traverse from the oaks and birches to the spruces and larches.

The waterfall was a white 40 ft. spout that day, a real focal point, with a path climbing steeply to the right through the woods. Soon we were on a forest road leading eastward but as yet no sign of our hill which is crowned with a look-out hut.

Pat told me he had got wandered trying to find it on his first visit. Round a wooded bulge and it was there, an outpost of the Menteith Hills, once a lime quarry, and with a nice face of rock whose green ledges showed its mineral richness for flowers.

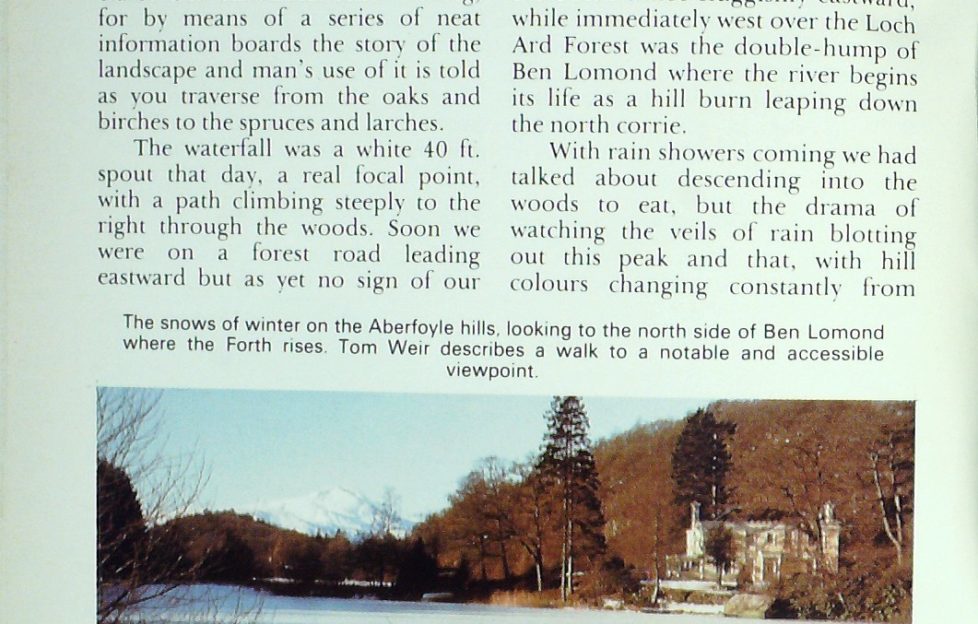

A short sharp finish and we were on the lumpy top at 1311 ft., at a transition point between the Lake of Menteith and the flat lands of Flanders Moss where the Forth winds sluggishly eastward, while immediately west over the Loch Ard Forest was the double-hump of Ben Lomond where the river begins its life as a hill burn leaping down the north conic.

An “Almost Too Successful” Visitor Centre

With rain showers coming we had talked about descending into the woods to eat, but the drama of watching the veils of rain blotting out this peak and that, with hill colours changing constantly from grey to blue and black over green spruces, gleaming lochs and rivers, was too good to miss.

The David Marshall Lodge Visitor Centre has been a great success story since it was gifted to the Forestry Commission by the Carnegie Trust in 1960. “It’s almost too successful” commented the head forester, “too many people hang around it when they should be spreading out, enjoying the different paths in the park.”

Forest Ranger Barry Martin does a lot to encourage visitors to be more adventurous, but to my surprise I heard that the special Forest Drive for motorists was under-used.

Pat was enthusiastic about it.

“It’s very peaceful. You pay your £1, drive in and you can get to great spots for picnics. I take my grandchildren to places laid out specially for play. They love it. You can drive round the west end of Loch Drunkie, leave the car and have little walks on the footpaths. You’ve got Loch Achray and Loch Venachar to explore. I think it’s great value, worth it for the seclusion and quiet you get.”

The Queen Elizabeth Forest Park extends of course from the Aberfoyle woods and the Trossachs, across Ben Lomond to Loch Lomondside, and it was there I had another walk on a forest trail that was new to me at Sallochy about half-way between Balmaha and Rowardennan.

To enjoy this to the full you should obtain the booklet for it at the Warden’s shop at Cashel Camp Site nearby.

It is the perfect expedition for a windy day, for the shelter is marvellous as I realised when I left the stormy loch-shore and entered a haven of peace on a path climbing steeply from oaks and alders to Sitka and Norway spruces.

For me the grassy ribbon of path between the dense stands of trees was made interesting by the speed at which it gained height, then traversed right through cypress and oak and birch, to turn sharply left into a rectangle of grey ruins in the form of a spacious farm courtyard. An explanatory notice-board told that it was the clachan of Wester Sallochy built 200 years ago and to house live families.

On this high level the folk worked the place, rearing cattle, taking them to the high pastures in summer, while others got on with working the infield and outfield to produce as much food as they could for themselves and their cattle. No doubt it would be a simple diet, oatmeal and milk products mostly. Wool from their sheep would make their clothes, and for warmth there would be a fire in the middle of the earth floor with the smoke finding its way out through the thatch.

Improvements came, slates instead of thatch, fireplaces and chimneys, even a mantelpiece, installed perhaps a hundred years later when the clachan had become a one-family farm. That farm was finally abandoned only 40 years ago, and the tall spruce plantation which hems it in is only 25 years old.

Living history indeed.

A Productive Hillside

This hillside must have been quite a busy place during the first 150 years in the life of this clachan, for the lower oakwoods were in full production, cut every 24 years and stripped of their bark for loading on to barges and sailed down the River Leven to the tanneries.

The method was to divide the woods in such a manner that every year an oak section was ready for cutting. After stripping, the wood could be used to make charcoal for iron smelting, the ore being brought here to Loch Lomond.

The high point of the trail is the slate quarry, its steep face gashing the hillside above a grey spoil heap laid out with benches for visitors to take their ease and enjoy the view.

From here you look across the loch to the other slate quarry at Luss, both quarries playing their part in the industrial revolution when the sudden growth of population made high demands on building materials.

Good as this spot is, there is a better one farther up if you have the energy to climb on to Dun Maoil Rock, a real protruding nose high above the plunging forest commanding Ben Lomond and the Arrochar Alps and that point where the narrow trench of the deep upper loch changes mood, broadening to expansive waters studded with wooded islands which is its unique glory amongst Scottish lochs.

I would give the Forestry Commission full marks for the way they have handled this bit of loch shore, with a fine camp and caravan park at Cashel, and at Sallochy barbecue braziers for which you can supply your own charcoal.

These places can be booked for private parties and are much in demand. Walkers will be interested to know that the West Highland Way path is being engineered along the shore as far as is possible though the present road will have to be followed in some places.

A Lost Treasure

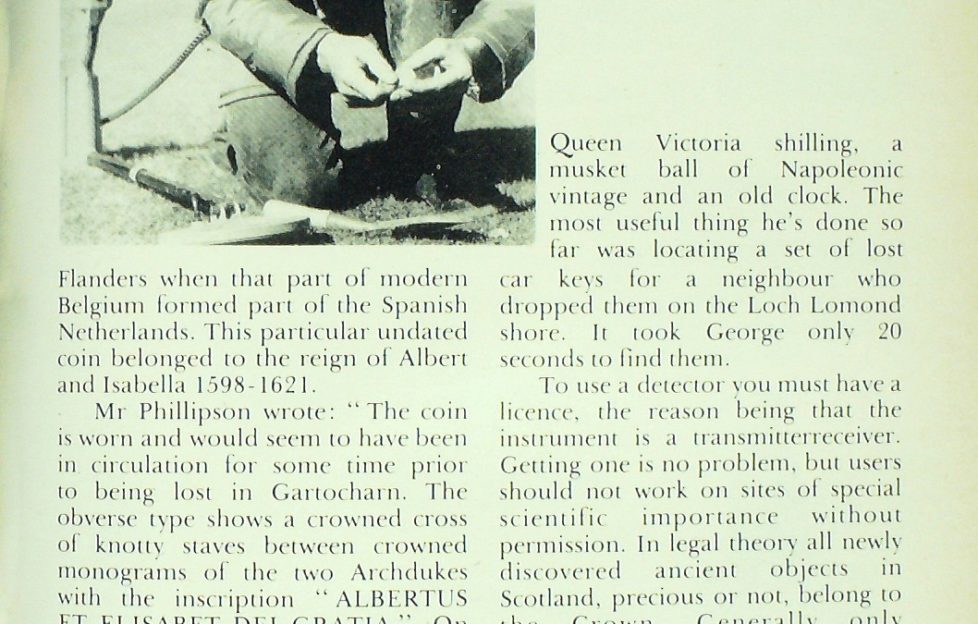

Back home in Gartocharn, I found my near neighbour George MacDonald in a state of excitement over a coin he had found with his metal detector. He chose a place where people go brambling and when he came across a George V half-crown dated 1923 he was encouraged to keep on trying.

Sweeping the instrument back and fore, suddenly came a very strong reading on the dial. Digging down eight inches with his trowel he unearthed a silvery and rather irregular coin with all the hallmarks of the ancient and unusual.

To find out what it was he sent it to Kelvingrove Museum and from Mr David W. Phillipson, Keeper of the Dept. of Archaeology, Ethnography and History, learned that he had found a half-patagon struck in Flanders when that part of modern Belgium formed part of the Spanish Netherlands.

This particular undated coin belonged to the reign of Albert and Isabella, 1598-1621.

Mr Phillipson wrote: “The coin is worn and would seem to have been in circulation for some time prior to being lost in Gartocharn. The obverse type shows a crowned cross of knotty staves between crowned monograms of the two Archdukes with the inscription “ALBERTUS ET ELISABET DEI GRATIA”. On the reverse is a crowned Spanish coat of arms surrounded by a collar representing the golden fleece. The inscription reads ARCH I D AUST DUCES BURG ET CO FL Z.”

For George it’s his best find ever. Since March he has detec ted 140 old pennies, 62 three-penny bits and 80 old ha’pennies, found an 1899 Queen Victoria shilling, a musket ball of Napoleonic vintage and an old clock.

The most useful thing he’s done so far was locating a set of lost car keys for a neighbour who dropped them on the Loch Lomond shore. It took George only 20 seconds to find them.

To use a detector you must have a licence, the reason being that the instrument is a transmitter-receiver. Getting one is no problem, but users should not work on sites of special scientific importance without permission.

In legal theory all newly discovered ancient objects in Scotland, precious or not, belong to the Crown. Generally only particularly rare or unusual finds are claimed. Treasure trove is confined to gold or silver. Rewards are paid to the finders, based on the market value of the coins.

Articles are returned if not required. Kelvingrove Museum would make an offer for George s rare coin if he wanted to sell it but he prefers to keep it and I don’t blame him.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday!

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.