Tom Weir | Old Friends And New Islands

Back on board the trusty Mysie, Tom Weir, Iain Smart and Graham Tiso took a trip round the lesser-known islands of the Inner Hebrides

To a yachtsman a first-time landing on an uninhabited Hebridean island is an event for the record, like a new Munro to a mountaineer. Iain and I were well pleased with ourselves on the rocky volcanic crest of Insh Island in the Firth of Lorn. Behind us was the southern fringe of Mull in a shower of rain, while in front the cottages of Easdale gleamed white in the sun.

Graham, who had been here before suggested making the landfall.

“It’s very unusual with jagged pinnacles and a line traverse round the rocky coast, marvellous geological formations.”

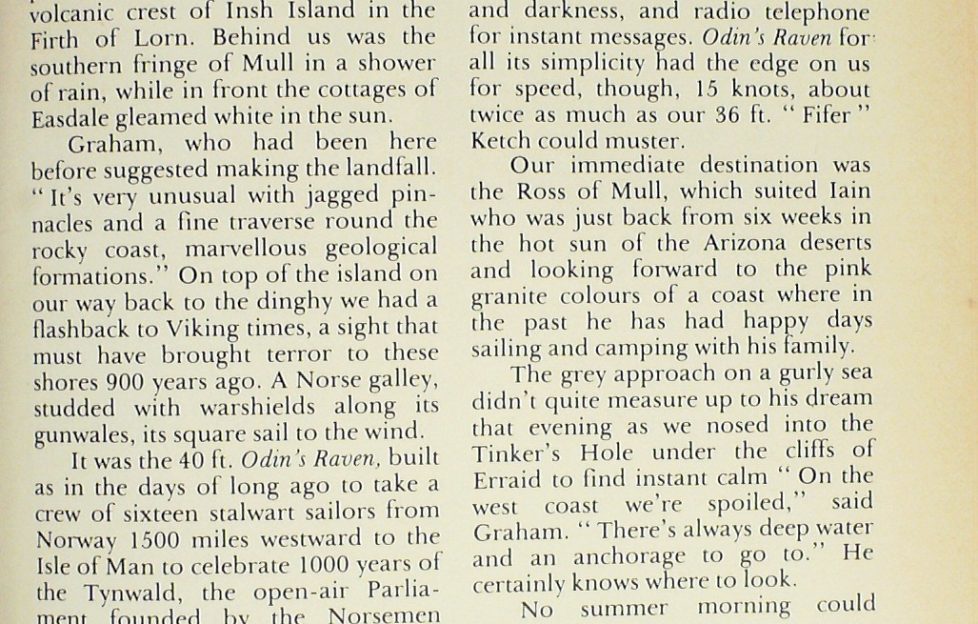

On top of the island on our way back to the dinghy we had a flashback to Viking times, a sight that must have brought terror to these shores 900 years ago. A Norse galley, studded with warshields along its gunwales, its square sail to the wind.

It was the 40 ft. Odin’s Raven, built as in the days of long ago to take a crew of sixteen stalwart sailors from Norway 1500 miles westward to the Isle of Man to celebrate 1000 years of the Tynwald, the open-air Parliament founded by the Norsemen when they brought democracy with conquest.

The vessel was a major breakthrough in the technology of the time, enabling tremendous sea voyages to be undertaken. We knew it would still be testing for the modern crew, totally exposed to the elements and we understood why they had stopped sleeping aboard after the big crossing of the North Sea.

Compared with their rowing-boat conditions, ours aboard the Mysie were positively sybaritic, with comfortable saloon and enclosed bridge fitted with every modern device; echo-sounder to gauge depth of water, self-steering mechanism which automatically keeps the boat on course, radar to deal with mist and darkness, and radio telephone for instant messages. Odin’s Raven for all its simplicity had the edge on us for speed, though, 15 knots, about twice as much as our 36 ft. “Fifer” Ketch could muster.

Under the Cliffs of Erraid

Our immediate destination was the Ross of Mull, which suited Iain who was just back from six weeks in the hot sun ol the Arizona deserts and looking forward to the pink granite colours of a coast here in the past he has had happy days and camping with his family. The grey approach on a gurly sea didn’t quite measure up to his dream that evening as we nosed into the Tinker’s Hole under the cliffs of Erraid to find instant calm

“On the west coast we’re spoiled,” said Graham. “There’s always deep water and an anchorage to go to.” He certainly knows where to look.

No summer morning could have been more full of colour than when we climbed from the dinghy straight up the vivid pink cliffs and saw Iona Cathedral and the white dots of the village houses.

While Erraid was the island of Iain’s memories, it was completely new to me and all the more delightful to discover its charm of flowers and wee narrow valleys set with cliffs with paths leading you on, most of them scented with bog myrtle. Suddenly we were at a little white hut with a pointed top like a tent.

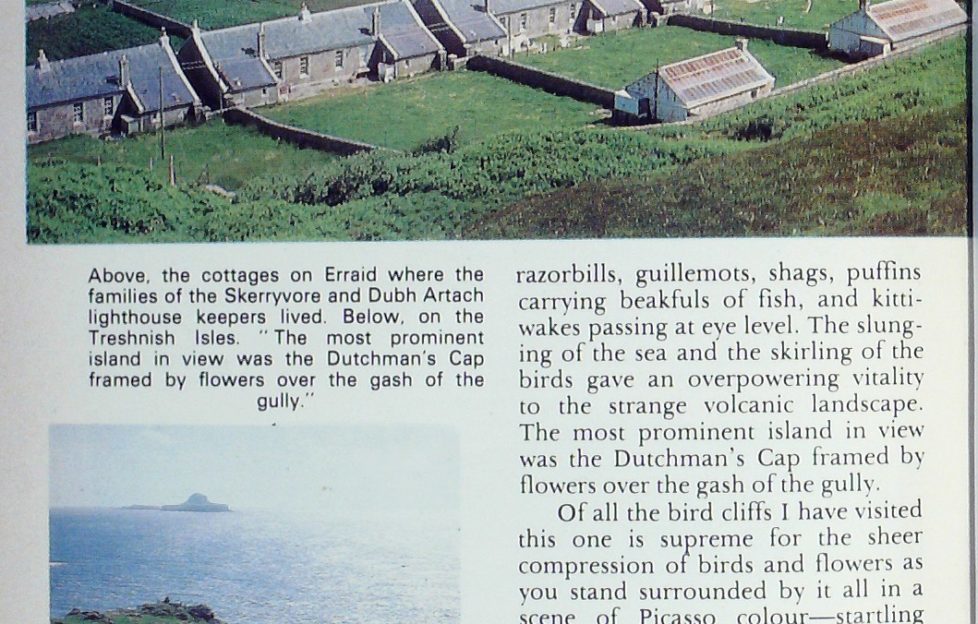

“The observatory,” explained Iain, “for signalling from here to the lighthouses of Skerryvore and Dubh Artach. The families of the keepers lived below. We’ll see them in a moment.”

In a step or two we were looking down on the neat granite row beautifully walled and above a fine pier. Signalling from the home base eleven and fifteen miles across the sea from the observatory must have been fun, and very comforting over a century ago when communications were primitive.

It was Robert Louis Stevenson’s family, father and uncle, who built the lighthouses on these wild Atlantic rock skerries, and it was in one of the cottages below us that the celebrated author is said to have written Kidnapped.

In the story David Balfour is shipwrecked on Erraid, marooned he thinks, until he discovers that at low tide he can walk across a strand to safety. Iain recounted to me a strange adventure that he had in what has become known as Balfour Bay, otherwise the Traigh Gheal.

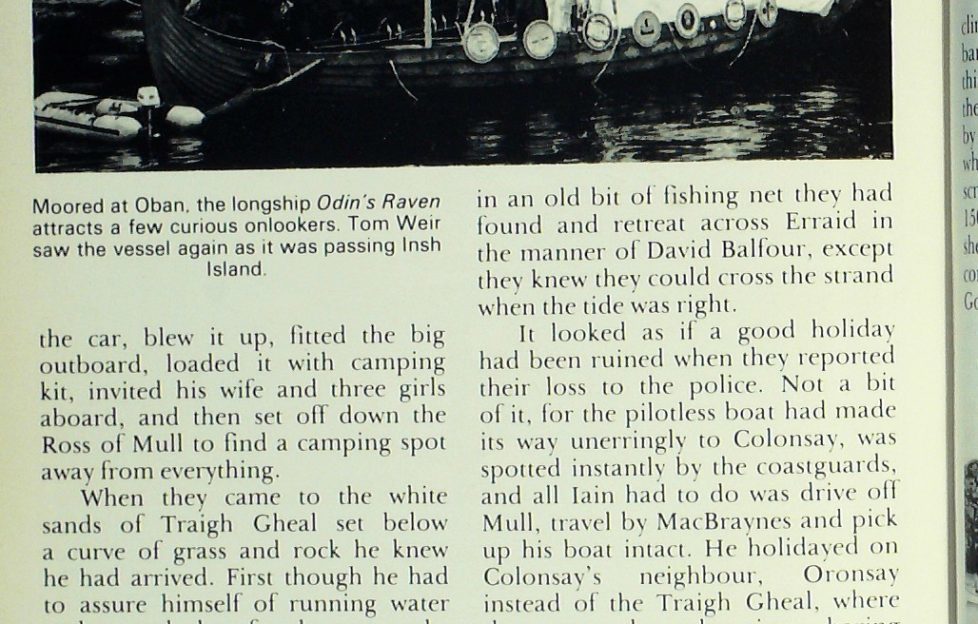

It came out as we looked from Erraid across to Kiloran Bay on Colonsay, seen as a little curve of yellow sand backed by the Paps of Jura. His saga began at Fidden on Mull just north of Erraid, where he took his inflatable rubber boat off the car, blew it up, fitted the big outboard, loaded it with camping kit, invited his wife and three girls aboard, and then set off down the Ross of Mull to find a camping spot away from everything.

An Unfortunate Event

When they came to the white sands of Traigh Gheal set below a curve of grass and rock he knew he had arrived. First though he had to assure himself of running water and a good place for the tent, so he beached the boat, unpacked a few things to get it to what he thought was a safe position for leaving unattended, and off he went with the family to inspect the place. It was on the way back he saw the boat was adrift.

Panic. He went after it, swam fast and hard, but had to turn for the shore as the distance widened dangerously behind him. Now they were stranded, with only the few things they had put ashore.

Nothing for it but to gather their belongings in an old bit of fishing net they had found and retreat across Erraid in the manner of David Balfour, except they knew they could cross the strand when the tide was right.

It looked as if a good holiday had been ruined when they reported their loss to the police. Not a bit of it, for the pilot less boat had made its way unerringly to Colonsay, was spotted instantly by the coastguards, and all Iain had to do was drive off Mull, travel by MacBraynes and pick up his boat intact.

He holidayed on Colonsay’s neighbour, Oronsay instead of the Traigh Gheal, where they returned another time, sharing the bay with otters who swam in the bay and made bouncing forays along the shore.

Even as we talked the brilliance of the morning was fading, and by the time we tipped anchor, grey rain clouds were advancing and it was raining as we nosed round Staffa for a landing place round the corner from Fingal’s Cave.

“I’ve never walked right round the island,” said Graham as we rowed ashore and did just that ignoring the soft drizzle as we edged the cliffs with the entire place to ourselves.

Nor had the weather improved as we left in thickening mist and heavier rain, steering for the narrows between Gometra and Ulva at the end of a varied day that seemed to have lasted a pleasantly long time.

So here was a chance to put another new island under my feet, Ulva, and a climb in the morning from a storm beach up the lava terraces providing a nice scramble before easing back to 1000 ft. summits.

The mists were lifting as we climbed to a mewing of buzzards and barking of ravens. No one lives on this west side now but everywhere are the ancient furrows of cultivation left by the former crofting population which at its peak numbered over 600, scraping a living from land and sea 150 years ago. Today the economy is sheep and some cattle and a road connects the island to flatter Gometra.

Great Bird Cliffs of Dun Cruit

I liked the look of Gometra as we sailed past it threading the reefs. Everest climber and Himalayan wanderer Hugh Ruttledge used to live there in the pleasant-looking big house among the trees, with four wee cottages close-by, with a lovely out-look to the Treshnish Isles where we were going. Joy, oh joy, skies were blue and the sun was shining out there though the big hills of Mull were in gloom.

Would our luck hold?

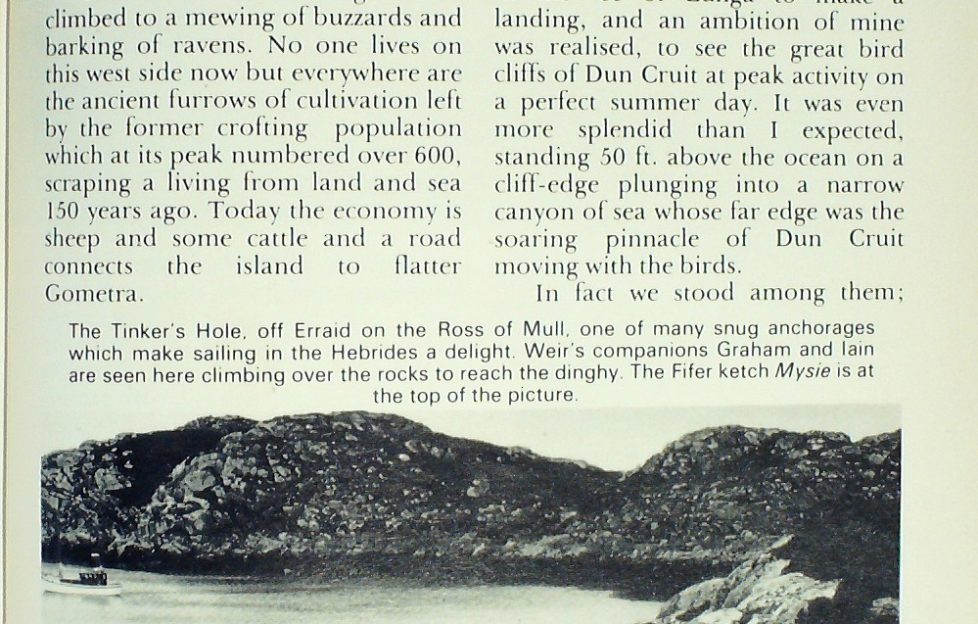

It did. The sea was calm enough in the lee of Lunga to make a landing, and an ambition of mine was realised, to see the great bird cliffs of Dun Cruit at peak activity on a perfect summer day. It was even more splendid than I expected, standing 50 ft. above the ocean on a cliff-edge plunging into a narrow canyon of sea whose far edge was the soaring pinnacle of Dun Cruit moving with the birds.

In fact we stood among them; razorbills, guillemots, shags, puffins carrying beakfuls of fish, and kitti- wakes passing at eye level. The slunging of the sea and the skirling of the birds gave an overpowering vitality to the strange volcanic landscape. The most prominent island in view was the Dutchman’s Cap framed by flowers over the gash of the gully.

Of all the bird cliffs I have visited this one is supreme for the sheer compression of birds and flowers as you stand surrounded by it all in a scene of Picasso colour—startling yellows of lichen, green ledges, blue sea and sprays of flowers.

We were there at exactly the right time for, as on Erraid, the great moment lasted only two hours or thereabouts before an overspreading greyness came from the west.

Even so, we managed to reach the southern tip of the island and get back to the boat before the squalls set in—a great sailing wind for the north tip of Mull which was on our route for an anchorage in Tobermory or Loch Sunart.

Once through, the tortuous passageways of the Treshnish, Graham hoisted the sails, shut off the engine and we were away to the fine sound of creaking sheets and slaps of wind as we rolled and bumped in bursts of spray.

Graham, who loves lone sailing, prefers doing everything himself aboard the boat, and was content that we have a lie down on our bunks while he stood hour after hour at the wheel. It was dark by the time we were wakened by the sound of the engine, a sign that we were near our anchorage in the lee of Oronsay Island, but it took some radar work to find the best spot on a night of unquiet sea.

Once daylight came I saw where we were, just opposite Glen Borrodale Castle on the Ardnamurchan shore, with Loch Teacuis just round the corner, but too rough for us to try its shallow waters. All the same with the wind still in our favour it was going to be a pleasure rounding the tip of Morvern and sailing through the Sound of Mull for the Lynn of Lorn and home to our anchorage on Loch Creran.

Again nature turned up trumps. The greyness passed and the sun shone as we came up the length of Lismore which made a very nice finish indeed to our round trip which had lasted six days.

Where Eagles Dare

It’s been said that the untamed coast and the wildest mountain tops are the only natural landscapes remaining in Britain, uncontaminated by modern development. It explains, I think, why a keen mountaineer like Graham has become addicted to exciting voyages and lonely anchorages. I do not have his confidence in the water, but feel in my element on the crags; not so my friend Pat.

Much as he loves the high hills he has no head for heights, but there was the gleam of the chase in his eyes as he told me of a big crag where a golden eagle had built an eyrie a few years ago but had been shot off the nest by a prejudiced gamekeeper. As an authority on eagles with a licence to study and report on them, he asked me if I would join him on a visit to this crag in the hope that the bird had bred again.

We took to the precipitous slopes, first up a burn of waterfalls, then along the base of the dills and boulderfields. Then came a great moment when out from the face, the silhouette of a huge broad-winged bird appeared and passed over us out of sight in a few sweeping flaps of ragged pinions. High on the face under a great protruding beak of rock was the enormous pile of sticks of the eyrie.

What a spot. I had never seen a more impressive eyrie. Question was, could we get to it? Not directly as Dave and I found, with a long drop below us and very little for hands and feet.

However, there was an airy shelf running across the face that brought us out level with it, and we could shout down to Pat that there was not one but two well-feathered eaglets in golden brown, not far from the flying stage. One was standing up and we could see the blink of its eyes, and on the rim of the nest what looked like a crow. At the back of the eyrie the second eaglet was lying down.

Leaving the eyrie we climbed to 8000 ft. to enjoy the white mouse- ear chickweed, the yellow saxifrage and the alpine ladies mantle blossoming with the least willow, tormentil and milkwort. In great spirits we descended after a day that had made us all feel young and light in heart.

Read more from Tom’s Archives next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.