Tom Weir | Shetland Folk

In the second in his 1979 two-parter on Shetland, Tom Weir got to know a few of the locals and heard of their history

I am sure it is true to say that the German occupation of Norway in 1940 did a very great deal to focus the attention of young Shetlanders on their Norse origins as refugees began arriving in fishing boats and the flag of “Free Norway ” was hoisted on Lerwick Town Hall mast.

Like most folk, I had read about the bold operations of the freedom fighters who crossed and recrossed the North Sea so often that it became known as “taking the Shetland bus.”

The service did its sabotage work so well inside Norway that it wore down a large force of the German Army and took pressure off other spheres of operation.

A Dangerous Mission

Now in Scalloway, the old capital of Shetland, I had the chance to hear first-hand accounts of these adventurous trips from a humorous little man by the name of Jack Moore whose boat-repair yard kept the “bus” going. Down at the slip he showed me the old lathe in his workshop where spare parts of Norwegian engines were turned out to keep the risky crossings going.

He told me about some of the long journeys which began here, sea passages” of a thousand miles to the Lofoten Islands and beyond.

“The boats used to leave Scalloway at a time that enabled them to enter Norwegian waters under maximum darkness. The intelligence reaching us was marvellous,” reminisced Jack, “and from the information supplied we used registration numbers of boats which were safely tucked up in their home ports. We knew even the Christian names of the Germans on duty in different ports.

“Our boats would arrive in Norway as if in from a normal night’s fishing, but they would be carrying weapons and explosives. They would land saboteurs in Norway and sail back with a new crew to Scalloway. I’m proud of the fact that we have no record of any of our engines breaking down, though the boats themselves took an awful beating and were badly shot up. It was amazing that some of them got back.

“All the woodwork was done by Norwegians of the Independent Force. They were billeted in the old garage just above the slip and they worked in my shed. They were busy times. My wife hardly ever saw me! We’ve had a lot of the old gang back here since, and we’ve visited them in Norway. We’ll never forget those days of working together.”

It was not until I was in Jack Moore’s house high above the bay that I saw how he had been honoured with the British Empire

Medal and an inscribed plaque from the Norwegian Independent Force. He remembered terrible casualties of that lonely war, but spoke little of his own grief; two years ago his young son, who had just taken over the business, was drowned at the boat-repairing slip while inspecting the hull of a boat—not only a family tragedy but a big loss to Shetland.

Walking along, looking at the boats, I had the good luck to meet a small, thick-set man by the name of Geordie Hunter, who represents the Shetland Fishermen’s Association and, as their general manager and secretary, fights for their rights. His 30 years as a skipper were written in his strong face, and I wasn’t surprised to hear he had been a whaler in his time in Antarctic waters.

“Without fishing there would be no Shetlanders,” he declared. “Fishing was the mainstay of 90 per cent, of the population living on these islands, and our future will depend upon it again after the oil runs out— that is, if there are still any fish to catch. Iceland and Faroe have extended their fishing limits and foreign boats are coming here and scooping up everything. We must have an extension of limits around Shetland if we are to survive.

“As it is, we’ve to contend with pipe-lines, tankers and oil pollution in the good fishing of Yell Sound. In January this year I was one of a five-man delegation to Strasbourg putting the Shetland case. We have the E.E.C. supporting our case for special protection from over-fishing by large trawlers. But the British Government hasn’t backed the regional fishing plan, so we have to sit back while the dispute between the E.E.C. and the U.K. argument on fishing policy wrangles on.

The Shetland fleet is 80 boats, employing some 600 fishermen, a fleet that could fish for herring continuously using traditional methods without harming the stocks. But we can’t compete with the big, well-equipped foreign boats. We don t want to, for they are using methods that can only result in a future fish famine. As things are, our fish factories in Shetland are facing problems and some have had to close. So while it was a record year for the harbour, the fisheries were down by £1 million.”

George Hunter and his association have the backing of the Shetland Island Council, who have put money from oil revenues into the ailing industry to help keep it alive. Nor were things helped by an exceptionally bad summer followed by as severe a winter of gales and snow-storms as anyone can remember. One record gust in Unst was recorded at 202 mph.

A Time To Rejoice

Yet winter in Shetland is a time to be enjoyed as I saw at Up-Helly-Aa when preparations that have taken a whole year for the Guizer Jarl Squad come to fruition in the torchlight procession and ceremonial burning of the galley ship 1 described last month. I didn’t get the length of the aftermath, however, the night of feasting and revelry which fol-lowed in 13 different hails in Lerwick as Guizer Squad after Guizer Squad filed in to cheers and hand-clapping to perform their “stunt ” and choose a dance.

My invitation was to Anderson High School, beautifully decorated, and with a huge spread laid on right through the night until breakfast- time for those with the stamina to watch no fewer than 48 turns performed by the ingeniously dressed teams which would take the length of this article to describe. Protocol demands that they put on their act in each one of the 13 halls and remain sober enough to perform.

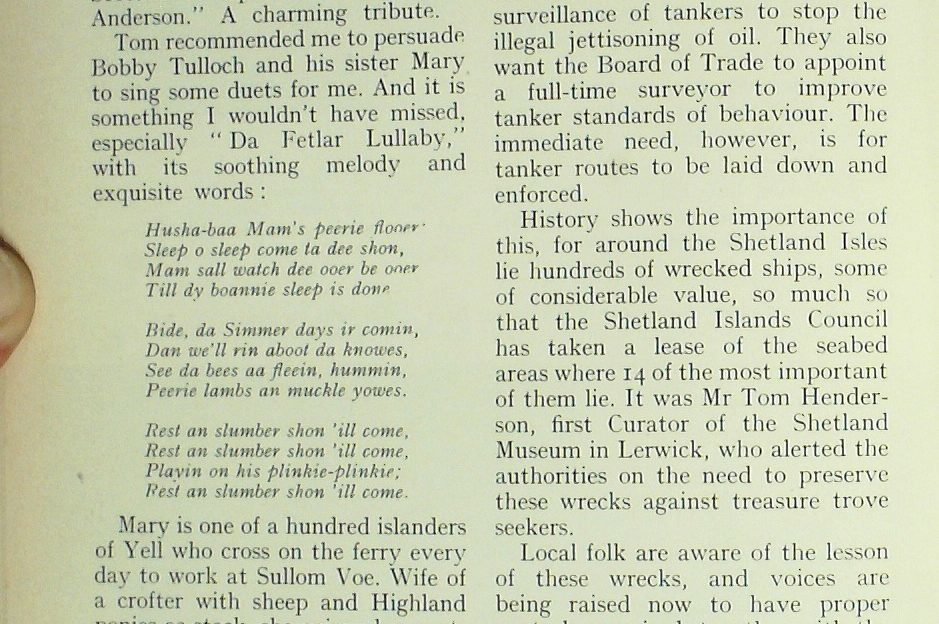

The highlight, of course, was the arrival of the Guizer Jarl Squad marching round the room, singing their special song and waving their battle-axes. You could feel the emotional uplift. I don’t know how they managed to look so fresh all through the night, for they had been on the go since nine in the morning, a 23-hour stint of almost non-stop activity.

I had first seen them marching after breakfast to the British Legion for the customary dram to prepare them for the rigours of the day, then down to the quay with the brass band playing and the first sight of the brilliantly-painted galley Kveldulf. Faces everywhere were wreathed in smiles. Their next visit was to the Town Hall to receive the Freedom of Lerwick before an invited audience, with Shetland Council Convener, Mr A. I. Tulloch, and Lord Lieutenant Mr Robert H. V. Bruce as principal dignitaries.

Here, after drinking from the silver quaich in the form of a longship, Jim Nicolson, the Guizer Jarl, told the story of Eigil Skallagrimsson, the bold Icelander of the Sagas whom he represented that day. Mr Tulloch spoke of the men who had come after the Vikings and who had kept alive the seafaring tradition.

That was probably the most formal of the day’s visits. Now the Squad were off to see the old folk, present themselves at schools, hos¬pitals and call at the Gilbert Bain Maternity Unit to see a very special baby boy born at 12.40 a.m. The father was Kenny Pearson, seen in my colour photograph with his proud wife Margaret and the baby, a fine present for a member of the Guizer Jarl Squad on Up-Hellv-Aa Day !

One of the nicest things about the whole Fire Festival is the way everybody is brought in, especially the womenfolk, without whom it would fizzle out, for their behind- the-scenes work contributes so essentially to the annual event. They help with the making of the fancy dresses, they co-operate by letting husbands and sons attend Squad nights week after week, and as hostesses they cook and bake to ensure that every one of the 13 halls can keep the party going all through the night.

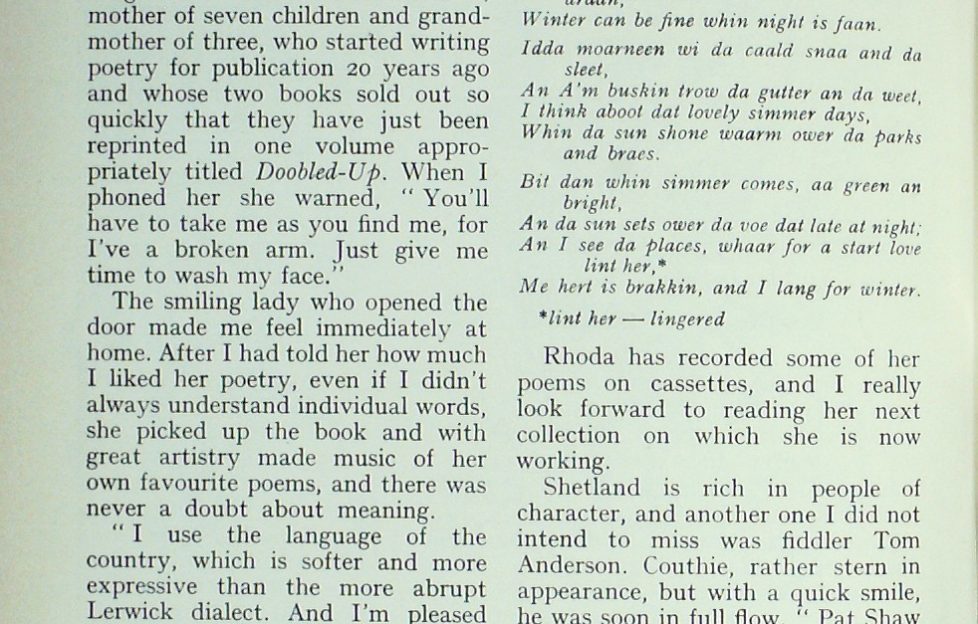

One Lerwick lady I specially sought out was Mrs Rhoda Bulter, mother of seven children and grandmother of three, who started writing poetry for publication 20 years ago and whose two books sold out so quickly that they have just been reprinted in one volume appropriately titled Doobled-Up. When I phoned her she warned, “You’ll have to take me as you find me, for I’ve a broken arm. Just give me time to wash my face.”

The smiling lady who opened the door made me feel immediately at home. After I had told her how much I liked her poetry, even if I didn’t always understand individual words, she picked up the book and with great artistry made music of her own favourite poems, and there was never a doubt about meaning.

“I use the language of the country, which is softer and more expressive than the more abrupt Lerwick dialect. And I’m pleased that the poems are so popular because I feel the language is under attack these days when radio and television are in every home.”

Despite the additional threat of the massive invasion of oil folk from outside, she hopes the Shetlanders will keep up the old tongue.

She told me it puzzles her where the inspiration for her poetry comes from.

“I can’t sit down and say I’m going to write a poem. The inspiration comes at inconvenient moments, often enough at lunch-time when I’m busy cooking, or it wakens me up at three o’clock in the morning and 1 have to write it down or I’ll forget. Or it can come because I’m moved by a natural event.”

Contrasts interest her, as in this poem:

WINTER

Da day is juist a blink, short efternun

Fadds awa ta da lang dark night dat shun

Bit whin da fire lowes up and da blind is draan,

Winter can be fine whin night is faun.

Idda moarneen wi da caald snaa and da sleet,

An A’m buskin trow da gutter an da weet,

I think aboot dat lovely simmer days.

Whin da sun shone waarm ower da parks and braes.

Bit dan whin simmer comes, aa green an bright,

An da sun sets ower da voe dat late at night;

An I see da places, whaar for a start love lint her,”

Me hert is brakkin, and I lang for winter.

*lint her — lingered

Rhoda has recorded some of her poems on cassettes, and I really look forward to reading her next collection on which she is now working.

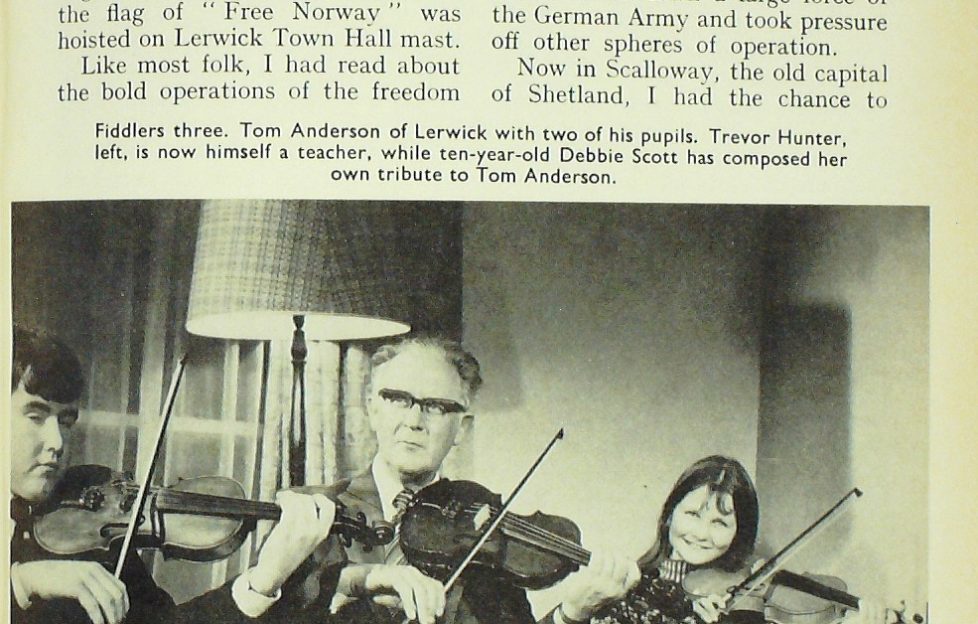

Shetland is rich in people of character, and another one I did not intend to miss was fiddler Tom Anderson. Couthie, rather stern in appearance, but with a quick smile, he was soon in full flow.

“Pat Shaw with his tape-recordings of Shetland music was a big influence in 1949, and now the interest is world-wide. When I retired from insurance a few years ago and put an advert in the paper for fiddlers to play together, 45 responded. This year for the second time I’ll be teaching Shetland fiddle style at a Stirling University summer school.”

He told me, “We don’t have indigenous music in these islands to compare with the Hebrides. Most Poetess Rhoda Bulter with her latest book, Dooblcd-Up, a selection of her poems written in the Shetland dialect.

Shetland music is borrowed—many of the tunes were brought by seamen who were fiddlers, Scots, Irish, English, Norse, but they were given a Shetland twist, so we have tunes for every occasion. I’ve been collecting with a tape recorder since 1947 and teaching for five years without a text book. But now I’ve written a book, Hand me doon da Fiddle, and its aim is twofold, to revive the Shetland speech by telling the story of each tune, and to explain the technique.”

Tom soon had his fiddle out and was playing tunes like “Da Merry Boys of Greenland,” for which Bobby Tulloch of Yell wrote some fine words :

Da news is spreadin trowe da loon:

A ship is lyin in Bressa Soond.

Tell da boys sho’s northward boond

Ta hunt da whale in Greenland.

Up aloft an set da sail,

Hingin on wi teeth an nail;

We’re goin north ta hunt da whale

Da Merry Boys o Greenland.

I wish I could quote the other rousing verses. What a grand afternoon of music and talk it was, all the better when two of Tom’s pupils came along, Trevor Hunter, now a teacher himself visiting schools, and little Debbie Scott, who, at 10 years old, played me one of her own compositions, “Debbie Scott’s Compliments to Tom Anderson.” A charming tribute.

Tom recommended me to persuade Bobby Tulloch and his sister Mary to sing some duets for me. And it is something I wouldn’t have missed, especially “Da Fetlar Lullaby,” with its soothing melody and exquisite words:

Husha-baa Mam’s peerie flooer-

Sleep o sleep come ta dee shon,

Mam sall watch dee ooer beooner

Till dy boannie sleep is done

Bide. da Simmer days ir comin,

Dan we’ll rin aboot da knowes.

See da bees aa fleein, hummin,

Peerie lambs an muekle yowes.

Rest an slumber shon ‘ill come,

Rest an slumber shon ‘ill come,

Playin on his plinkie-plinkie;

Rest an slumber shon ‘ill come.

Mary is one of a hundred islanders of Yell who cross on the ferry every day to work at Sullom Voe. Wife of a crofter with sheep and Highland ponies as stock, she enjoys her part-time job in the canteen, though she entirely shares her brother’s deep concern for the future of the sea-birds which are one of the joys of Shetland.

The first big spillage of oil at the turn of the year was bad enough ; it could be called an unusual and unfortunate accident. But fresh spills affecting south-west Shetland and Orkney since then have not been accidents. They were the result of tankers deliberately dumping oil, and their pollution slaughtered hundreds of seabirds. It has turned the word oil sour in the mouths of Shetlanders, many of whom fear a major disaster involving the wreck of a tanker. I was told that many tankers take dangerous short cuts near the Vee Skerries when they should be following the recommended route west of Foula. Council members are demanding helicopter surveillance of tankers to stop the illegal jettisoning of oil. They also want the Board of Trade to appoint a full-time surveyor to improve tanker standards of behaviour. The immediate need, however, is for tanker routes to be laid down and enforced.

History shows the importance of this, for around the Shetland Isles lie hundreds of wrecked ships, some of considerable value, so much so that the Shetland Islands Council has taken a lease of the seabed areas where 14 of the most important of them lie. It was Mr Tom Henderson, first Curator of the Shetland Museum in Lerwick, who alerted the authorities on the need to preserve these wrecks against treasure trove seekers.

Local folk are aware of the lesson of these wrecks, and voices are being raised now to have proper controls exercised, together with the best clean-up equipment obtainable to be kept here in Shetland at the ready.

It is this public concern for the environment which is really heartening, for, above money, the Shetlanders love Shetland, the sea, its cliffs, its birds, and a way of life in a hard country which has bred good and self-reliant people.

Read another of Tom Weir’s timeless columns here next Friday.

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.