Tom Weir | Trossachs To Kintyre

There is a very special kind of winter day when suddenly the countryside has a spring look. Everything seems to have a shine on it: beech bark, silver birch, the warm colour on the oaks and bluish sheen on plantations of Sitka spruce.

That’s how it was one frosty morning as we set off for Ben Ledi, revelling in the glorious clarity and enjoying the warmth of the sun through the car windows.

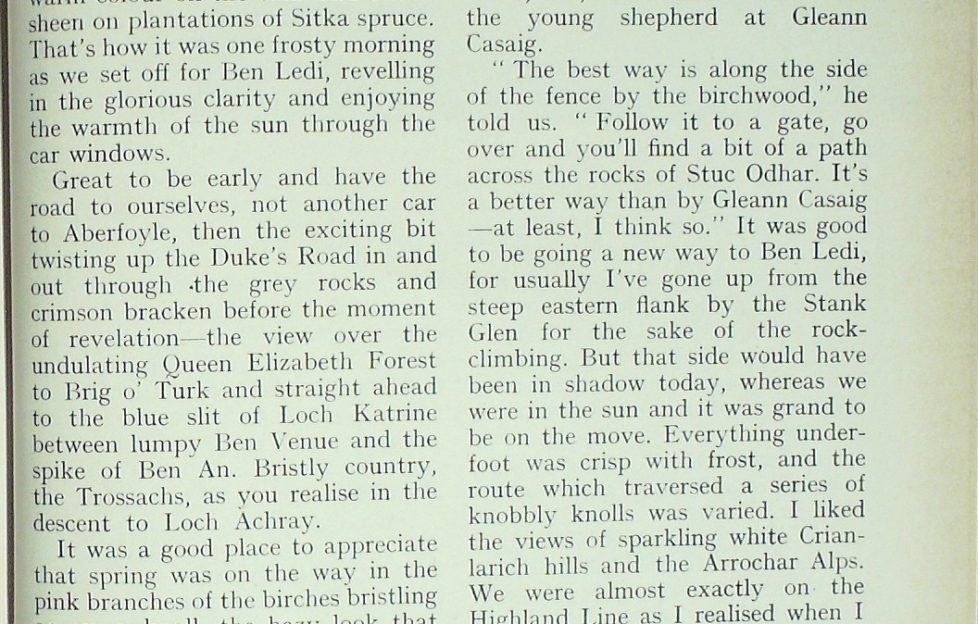

Great to be early and have the road to ourselves, not another car to Aberfoyle, then the exciting bit twisting up the Duke’s Road in and out through -the grey rocks and crimson bracken before the moment of revelation—the view over the undulating Queen Elizabeth Forest to Brig o’ Turk and straight ahead to the blue slit of Loch Katrine between lumpy Ben Venue and the spike of Ben An. Bristly country, the Trossachs, as you realise in the descent to Loch Achray.

It was a good place to appreciate that spring was on the way in the pink branches of the birches bristling on every knoll, the hazy look that comes with the rising sap in the lengthening days. Now we swung round the far shore of Loch Achray for Brig o’ Turk where a wee road climbs steeply to Glen Einglas.

McGregor Country

This is real McGregor country, and the name is still common hereabouts below the west face of Ben Ledi which we were going to climb from the wee loch which lies on its flank.

The older “Loch Lomond and the Trossachs ” O.S. map does not show this reservoir, created a few years ago to top up the waters of Loch Katrine. There are new bull-dozed roads, too, so we had a word with the young shepherd at Gleann Casaig.

“The best way is along the side of the fence by the birchwood,” he told us. “Follow it to a gate, go over and you’ll find a bit of a path across the rocks of Stuc Odhar. It’s a better way than by Gleann Casaig —at least, I think so.”

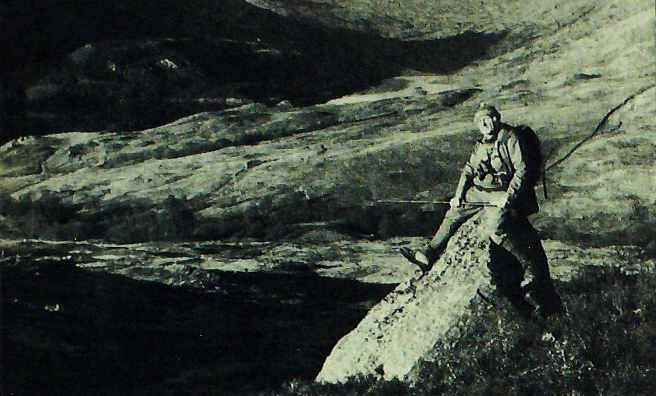

It was good to be going a new way to Ben Ledi, for usually I’ve gone up from the steep eastern flank by the Stank Glen for the sake of the rock- climbing. But that side would have been in shadow today, whereas we were in the sun and it was grand to be on the move. Everything underfoot was crisp with frost, and the route which traversed a series of knobbly knolls was varied.

I liked the views of sparkling white Crianlarich hills and the Arrochar Alps. We were almost exactly on the Highland Line as I realised when I took to the rocks for a scramble and found myself on pink Lowland sandstone, yet just above it was the schistose grit, the grey Highland rock.

Forging ahead, it was the sight of a falcon passing on my flank that made me look back. The bird was a merlin, flying low and fast. Beyond it was the jumble of the Arran peaks standing high above a sea of shimmering cloud between me and the Clyde.

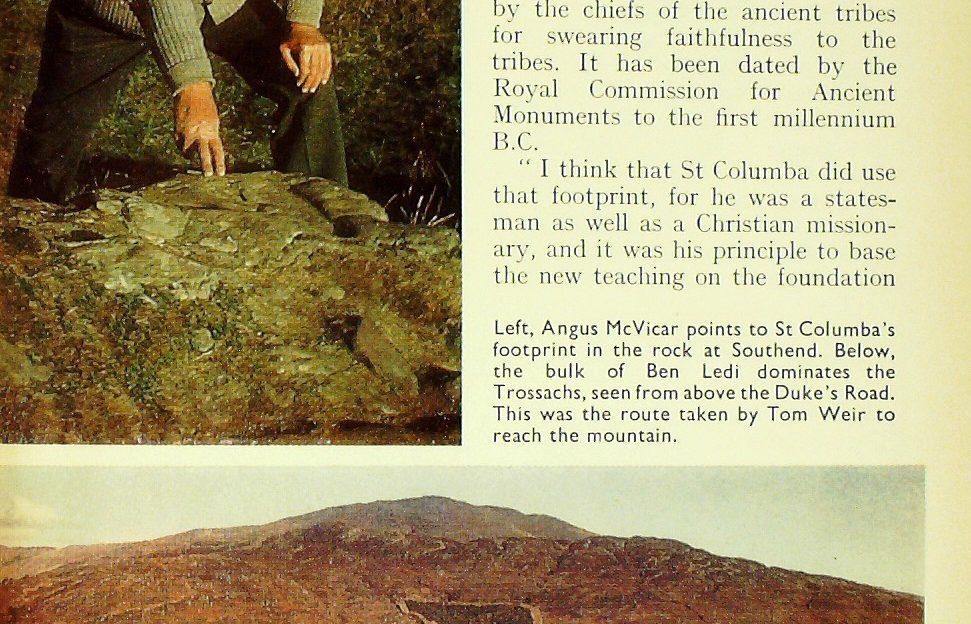

Soon we were on boulders and ice-hard snow patches where a white ptarmigan rose croaking from our feet, the first I recollect seeing on Ben Ledi. And up there we began to feel the bitter wind. On the ridge the grasses had sheaths of crystal ice, tinkling against each other as they shook, a glittering sight as magical as the panorama which suddenly opened before us.

To detail all that lay before us would be a recital. What made it was the contrast. Below us was the wee town of Callander and the Carse of Stirling extending to the big smoke of Grangemouth and Arthur’s Seat. And down in deep shadow lay the Pass of Leny, while the glittering snows of the high Highland hills rose to the north, their peaks stretching from Cowal to Atholl. Here was height and depth and every shade of colour.

“An absolute stunner of a day”

We struck north to the next little summit before descending west to Gleann Casaig where all the red deer stags and hinds seemed to be concentrated, enjoying the warmth well out of the wind. The biggest herd numbered about fifty, and after the icy top it seemed a different world as we plunged downhill in the pink- tinted light of a perfect afternoon.

Returning by Callander, we had still a last treat in store—one of the most marvellous winter sunsets I have ever seen. The feature of it was the red blaze of the sky echoed by the Lake of Menteith while everything else was in black silhouette. I would call that an absolute stunner of a day, when just to be alive was true joy

And we knew how lucky we were, for before returning home we visited a friend newly out of hospital after a difficult eye operation. For weeks she had lain blindfolded, unable to move her body. Now she could see a little, and we wanted to tell her of our day, knowing she would be able to visualise it and share our experience, for she, too, loves the hills.

I told her all about a visit to Kintyre I had made just a short time before when we again had the good luck to get a great day for an exploration of the peninsula which is the longest in Britain, its tip as far south as the Fame Islands in Northumbria.

We started off in Carradale, and I had forgotten what a lovely situation it had, with its fine salmon river coming down from unmistakably Highland hills, then through green parks to discharge into a two- mile sweep of the finest bay in Kintyre. You get a feeling of prosperity and vigour in this community which has at least four strings to its bow—fishing, forestry, agriculture and tourism.

There was only one fishing boat tied up at the modern harbour, and it was just about to go out and join the other dozen or so boats already out taking advantage of the fine weather. We learned from one of the crew that although gales had made catches difficult, prices for prawns and white fish compensated, and the hundred fishermen who fish out from here were in good heart.

The Forest of Carradale

Then in the forestry office we met Ranger Peter Strang, who led us along one of the nature walks through 30-year-old Sitka spruce which he had seen planted as seedlings. Seventeen Commission workers are employed in Carradale Forest, and Peter helps visitors to enjoy the walks when he is not doing his main job of deer control.

I hadn’t realised that this is one of the few places in Scotland where all four species of deer occur in the woods—roe, sika, fallow and red. The first two can be a nuisance in the 7000 acres or so of plantations. Peter keeps their numbers down with the gun. No snares or traps are used.

He told me there are only about 30 fallow deer, and that they used to be confined to the projecting arm of Carradale Point. The Point still supports a herd of white wild goats in the rocky area tipped with a vitrified fort. To reach this part you go through the attractive parkland of Carradale House, the home of Lady Naomi Mitchison.

I had long wanted to meet this distinguished authoress and traveller who has described her recreation as “Accelerating the Mills of God,” so it was a real pleasure to step into her spacious living-room-study looking out on the hills of Arran beyond the sweep of Carradale Bay. When I remarked that it must be nice to live in the old house of Campbell of Carradale, she looked a bit doubtful.

“Well, I’m not awfully keen on the Campbells. You see, my people were Stuarts and you know how we feel about one another. Of course, there are good Campbells, too, but Campbells in general make me feel a wee bit awkward, and, of course, there are quite a lot of ghosts and one thing and another about.”

“Haunting the house?” I queried.

“Well, I wouldn’t say no, but since we had a fire in the house the Grey Lady who used to be a terrible nuisance, has not reappeared. People were always saying to me, ‘I see you’ve got a cook at last’, and it wasn’t a cook, it was just the Grey Lady! She was always on the back stairs before they got burnt.”

An impressive résumé…

Knowing what an active part she has played in the Carradale community, and of her work on the Highland Panel, and acting as Tribal Advisor to Bakgatla, Bechuanaland Protectorate, since 1963, in addition to writing her books, I asked her how she found time to do all the things she did.

“Oh, that’s often quite a problem. Quite often I go to sleep thinking of all the things I haven’t done during the day. But we’re a hard-working lot, we Haldanes, and somehow we usually manage to get through at least twice what other people do. I’ve a lot of friends here and they help to keep me on the right path.”

We talked about her work on the Community Council, and of the small caravan site in her grounds which she set up to help the village tourist trade.

“It means more people coming to the shops, using the village hall, hiring boats and so on. A good deal of the future of the Highlands, and especially Kintyre, depends on this rather naughty thing of deploying their beauty to strangers, and although one doesn’t entirely like it, I think it’s got to be done. It is very beautiful around here. If only we could be sure of having a hot line to the Almighty to get a bit of fine weather during the summer!”

Listening to this small, white-haired lady talking, I found it hard to believe that I was with someone born in 1898 who had written over 40 books, was an officier d‘Académie française as long ago as 1924, and 11 years later had stood for Parliament as Labour Candidate for the Scottish Universities Constituency.

King of the Isles

Now we drove south by Torrisdale Bay under the highest peak in Kintyre, Beinn an Tuirc (1491 ft.), named after a fierce wild boar slain, according to legend, by Diarmid, progenitor of the Clan Campbell, hence the portrayal of a boar’s head on the Campbell crest. Looking to the hill from ruins of Saddell Abbey, I felt a deep sense of history for this is where the great Somerled was laid, the King of the Isles who drove the Vikings from Kintyre and the Southern Hebrides when he engaged them on an early January morning of 1156. Slain himself two years later, his body was brought to this monastery which he had begun. It was his son Ranald who built this Cistercian Abbey of Saghadail to enshrine his father’s body.

I liked the look of Saddell Glen, its greenery leading into the brown hills where sheep and cattle grazed on high knolls with traces of old lazy-bed cultivation around them showing it must be good ground. Forestry Commission trees give variety to the hill-shoulders. Near the sea-front was the village, many of the houses having wee boats in their gardens ready for a. quick launch into the Kilbrannan Sound.

The short day was slipping away so fast we had to skip Campbeltown, inviting as it looked, seen across its deep loch marvellously sheltered on the seaward side by Davaar Island, with views out to Ailsa Craig. Our destination was Southend to meet up with Angus McVicar, who, at 70 years of age, has written 70 books.

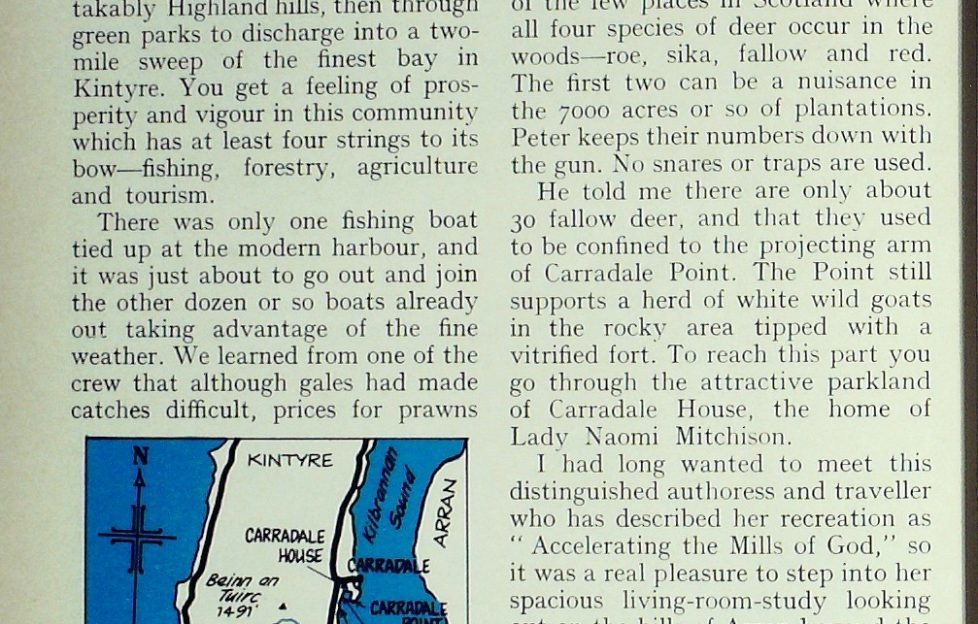

A quick cup of coffee with this couthie man and his wife, Jean, then off we went a short distance down the coast to look at St Columba’s footprints. The site was impressive, a big cliff with fulmar petrels sitting on their nest ledges, paired, waiting for the spring, while above them chattering jackdaws swirled about, taking no notice of a buzzard hovering on the slipstream. Below us, eider ducks bobbed on the water.

“These are the footprints,” said Angus. “But look—they are both right feet, one facing the east, the other to the north. One of these is genuine, and it goes away back before St Columba. It is the one to the east, and probably it was used by the chiefs of the ancient tribes for swearing faithfulness to the tribes. It has been dated by the Royal Commission for Ancient Monuments to the first millennium B.C.

“I think that St Columba did use that footprint, for he was a statesman as well as a Christian missionary, and it was his principle to base the new teaching on the foundation of the old. So I think he would pay homage to the beliefs of the tribe here by placing his foot in the print. The other print was made by a mason in his lunch-hour about last century, I believe.”

We talked then about Dunaverty, the rocky protuberance just across the bay where the Lords of the Isles built a fortress in the 13th century, though it did not become notorious for another 400 years when in 1647 the Marquis of Argyll with 3000 Campbells laid siege to 300 MacDonalds within the castle.

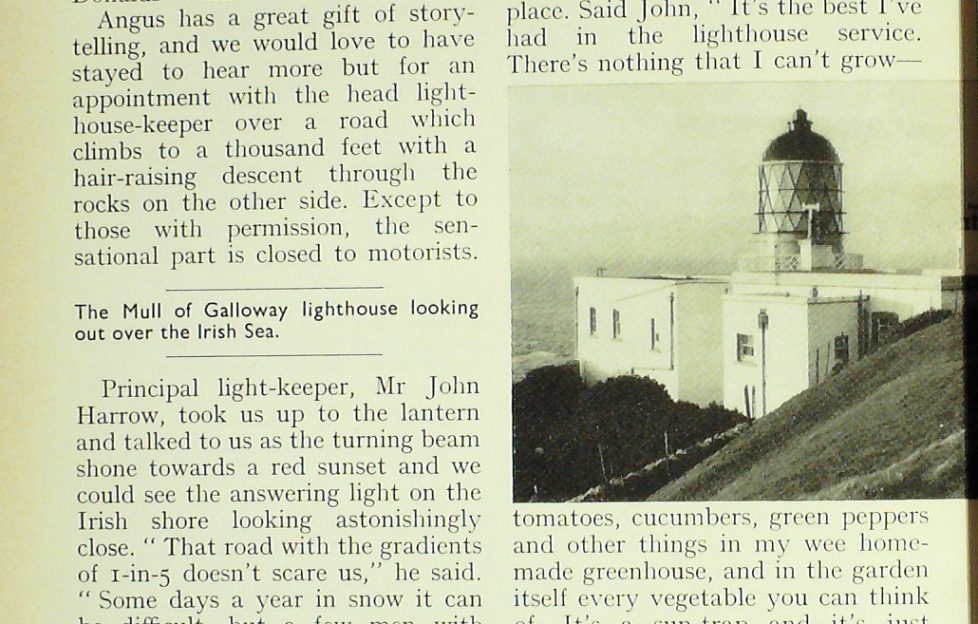

Angus has a great gift of storytelling, and we would love to have stayed to hear more but for an appointment with the head lighthouse-keeper over a road which climbs to a thousand feet with a hair-raising descent through the rocks on the other side. Except to those with permission, the sensational part is closed to motorists.

Principal light-keeper, Mr John Harrow, took us up to the lantern and talked to us as the turning beam shone towards a red sunset and we could see the answering light on the Irish shore looking astonishingly close.

“That road with the gradients of 1-in-5 doesn’t scare us,” he said. “Some days a year in snow it can be difficult, but a few men with shovels can work wonders. My wife and family are very happy here. We’ve enjoyed it for the four years we’ve been here, and I just hope I can finish my time at the Mull. My two assistants and their wives are very happy here, too, we’ve no complaints.

“It’s not isolated. The women can get away shopping in Campbeltown two days a week, and the men when they have their time off can do the same. The sea can be quite frightening on a wild day with a good gale of wind for anybody on the water. They say that seven tides meet here at the Mull of Kintyre. In these conditions big ships can look as if they were hardly moving they’ve got such a struggle to get through it. But on the calm days of summer it’s just beautiful here.”

The lighthouse is perched 260 ft. above sea level. It rarely gets salt spray, so for gardening it’s a good place. Said John, “It’s the best I’ve had in the lighthouse service. There’s nothing that I can’t grow-tomatoes, cucumbers, green peppers and other things in my wee home-made greenhouse, and in the garden itself every vegetable you can think of. It’s a sun-trap and it’s just beautiful. We don’t need to go to Spain, this is such a charming place.”

Sitting below the light in the snug sitting-room, drinking tea and chatting to the family, we were loath to leave. One thing we were very sure of: Kintyre is a superb place to live, and there are some very contented people there.

Read more from Tom Weir’s archives next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.