Tom Weir | Islands and Highlands

No matter even if it was a dreary day, chilly and with grey clouds solidly down on the hills of Harris, Iain and I were having the pleasure of sailing to a new island under the guidance of Graham Tiso who had been there before

We were having our annual “Three Men In A Boat” outing on the 36-ft Fifer ketch Mysie. The skipper was in great form, having sailed her solo from Oban to Skye, but the pair of us were feeling just a bit queasy, so we cheered up when, nine hours out from Uig, we heard the cry of “Monachs Ho!”

“Wait until you get ashore among the birds and flowers”

There was not much to enthuse over, just a low line of sand dunes reefed by jagged rocks where the sea broke white. “It looks nothing, but wait until you get ashore among the birds and flowers,” said Graham. “The colours were fantastic when I was here during a heatwave, and I’ve been dying to come back ever since.”

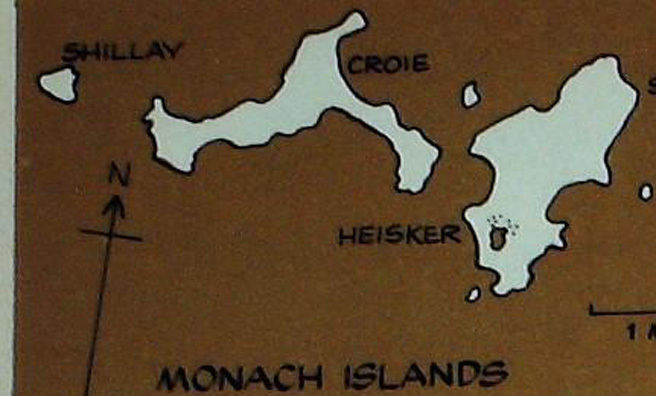

We were heading for the north tip of Heisker, keeping well out between it and an ugly rock called Stockay. Ahead we could see the one house that is still upstanding on the now uninhabited Monachs, and at that moment we saw a lobster boat heading towards us, waving us back round the point and shouting when he drew close that the lee of the next island lying west would be safer if we were looking for an anchorage. In fact, he was directing us to a bay called the Croie, where Graham had anchored in 1976.

A good night in the bunk was just what we needed, and when I wakened in the morning it was to hear skylarks singing above the white sands and green fringe of the Monachs. Soon we were in the dinghy and rowing the half-mile to Heisker, where I was amazed to see fulmar petrels squatting on the faces of the little sand dunes above where we hauled up the boat. In the absence of cliffs, the fulmars were nesting here at ground level, on the dunes, in the mined houses, even on the grass below old stone walls.

The whole machair was alive

Beyond the dunes the machair was yellow with flowers, mainly buttercups, trefoil, bedstraw and silverweed. The first sign of life there was an eider duck scrambling off its four chipping eggs. But the whole machair was alive: dunlin were reeling joyously; wheatears and meadow-pipits flitted across our path, redshank piped, and a sound I had not heard in the Hebrides for many a year sent my head up — little terns, the smallest of our sea-swallows – flying back and forward carrying minnow-sized fish to their nests in the dunes. Peewits by the dozen tumbled in the air, a snipe was drumming, and oyster-catchers seemed to be everywhere.

The centre of most of the activity was the village area, only ruins now except for the school which is in good repair and in use as a base for visiting lobster fishermen who sow their pots far distances round these islands.

Graham had a puzzle for me. “There’s a feature of these Monach house ruins I’ve never seen anywhere but here. You see how the back bit of the house is stepped-up to make a raised platform of stones, with what looks like a fireplace and a horizontal flue leading from it into a stone-lined chamber like a great pot. I’d like to know what it was for.”

It looked like a corn-drying kiln

I said it looked like a corn-drying kiln, that the grain would be put in the stone-lined chamber and a slow-burning fire lit to send the heat through the flue and make the barley or oats fit to store. And I have had my view confirmed by a lady who was brought up on the Monachs from 1921 to 1931, and whose mother was born there. Alas, she declines to let me use her name, but this is what she tells me:

“It was a self-supporting community. We didn’t want for anything. Everybody tilled the land and there was fish galore round the island. There were plenty of fat rabbits — my mother remembered them being introduced to the Monachs — we used to eat cormorants, and there was plenty of other wildfowl. Everybody helped each other. When I went to school there were fifteen scholars, but the roll was as high as a hundred at one time.

“I went to North Uist to finish my education, and I saw the island go down during my time. At last only two families were left. Quite a number of folk moved to North Uist. It is only eight miles from the Monachs to North Uist, but it’s a difficult stretch of shallow sea to cross. Once, when I went home for my Christmas holidays, it was the first of February before I could get off the island again.”

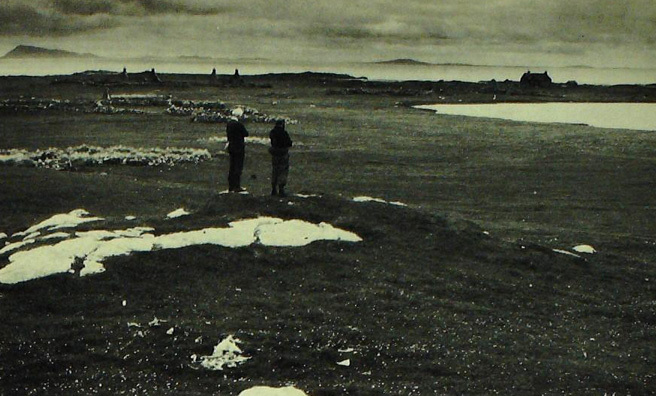

The highest point is only 50 feet above sea level

The Monachs show little trace of former cultivation now. Sheep graze the machair, and the highest point is only 50 feet above sea level. From up there you can appreciate the simple topography of reefs which have been heaped up with sand then fixed by the tough marram grass to make a soil which is composed of millions of shells.

I wish I had seen Heisker when cows grazed, and every house was thatched with marram. Then I might have heard the story, handed down by oral tradition, of the big storm of 400 years ago which changed the sea level to engulf the township of West Baleshare on North Uist and isolated the Monachs in a way that they had never been before. Until that cataclysmic event it had been possible to walk from North Uist to the Monachs at low tide.

Nowadays the township machair gives winter quarters to a big flock of barnacle geese from Greenland, but it was other Arctic birds which held our interest now, the big colony of terns occupying the bouldery shore, a positive blizzard of white wings criss-crossing, screaming, hovering, darting down with fish to feed their tiny young, or dive-bombing intruding gulls and hoodie crows.

Soon they had a fresh target as we tiptoed gingerly across the nesting area until it was hardly possible to avoid the crouching young or chipping eggs round our feet. Graham took a skite on the head from a swearing bird, but the main attacks were being directed at the downy young of herring gulls, running to escape the inferno.

There was a bigger surprise to come…

Down in the bay beneath us were rafts of eider drakes, resplendent in black and white but eclipsed for vividness by the shelduck keeping them company. Watching a flight of turnstones fly below us, there was a bigger surprise when about 20 bar-tailed god wits rose in elegant streamline, showing long straight bills as they passed.

A fresh-water oval of loch is a very pleasant feature of the township machair, and on it floated a combination of birds that was unique to me — a flotilla of tube-nosed fulmars with a few tufted and mallard duck, plus a single coot.

Now we began to think of getting back to the boat for the fair spell was passing and the exciting view of St Kilda hunched on the western horizon had vanished. The wind was getting up, and once aboard the Mysie, Graham decided to move to the most westerly of the Monachs, Shillay, where he expected to find a better anchorage beneath the high tower of the abandoned lighthouse. We liked the idea, too, of exploring this rocky extremity where the Atlantic seals were gathering to have their pups. Something like 2000 pups are born there every autumn.

It was northward again

That interlude over, it was northward again to find another island new to us – Taransay, in the big mouth of West Loch Tarbert separating North and south Harris. We enjoyed it there, spending the whole of a day doing a complete round of the island in a traverse of a dozen miles of rock and shell-sand coast, including a climb to a chain of wee lochs, one of them with a causeway leading to an ancient defence dun. The outlet burn was interesting lower down, by reason of the ruins of two wee watermills for grinding corn.

Only one family lives on Taransay now, but by the lazy-beds of former cultivation which are everywhere, the island must have carried a big population in former times. Unfortunately, it was the Sabbath or I would have gone to the door of the house for a chat with the farmer, whose mainstay is Cheviot sheep and store cattle.

It was time for my wife to have a wee break

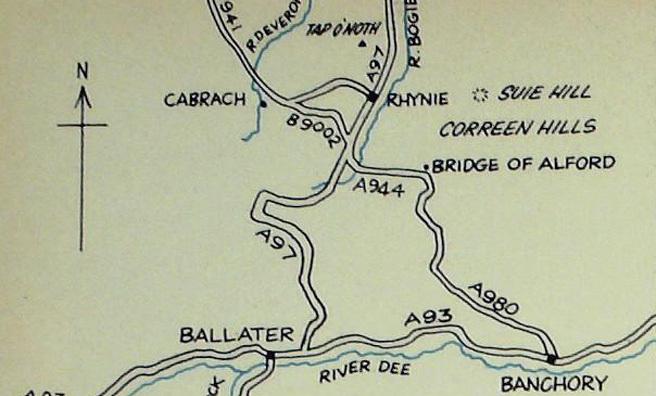

Back home, it was time for my wife to have a wee break, so we set off for Deeside to meet up with Adam Watson for an outing or two from Banchory. We had hoped for a day on the hills, but with the clouds down on Lochnagar and a westerly bringing rain, Adam’s suggestion was to head due north until we found better weather. We found it at Rhynie, so the expedition had to be Tap o’ Noth, a commanding peak I’ve looked at often enough. Now was the chance to reach its 1851-ft summit.

Tap o’ Noth, like Bennachie, is a terminal point of the Grampians. Both were fortified points of Iron Age people, whose villages lay inside summit defence walls.

Adam whetted my appetite by telling me that this one on the Tap was unusual in that the outer defence ring had been vitrified — its rocks had been fused together by heat. So up the steep heather of the south face we went, a climb enlivened with screes and rock outcrops.

In no time, it seemed, we were stepping over the vitrified rim into a big grassy oval where the village had been. No chance of taking the inmates who lived here by surprise, with the countryside lying round them like a map, the uplands of the Deveron and the Bogie, fields and woods and gentle hills stretching in a veritable sea.

This is the countryside of long winters

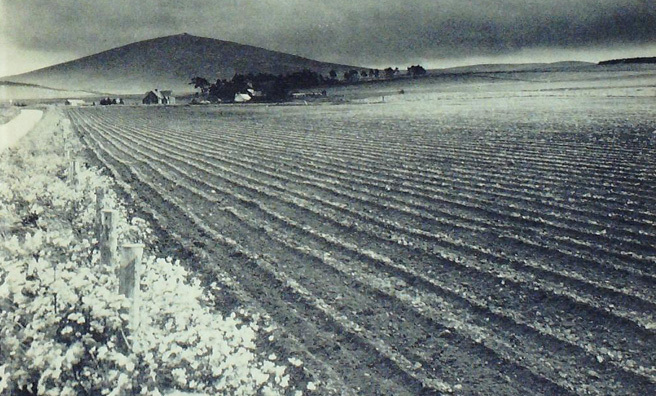

After that we motored by the B9002 to the Cabrach, passing through strange little knobbly hills of ruined homesteads, places where even to get subsistence from the land must have been difficult, for this is the countryside of long winters, where the snow falls early and lies late. And the same holds true of Cabrach, the name for little more than a post office, since the school lies empty and adjacent ruins speak of dereliction.

Adam quoted me a poem:

There’s a quintry in oor quintry caad the Cabrach,

Tur the river’s caad the Rooster and the com throoshter,

And there it dings on, naither upplin or davalin,

For sax ooks on eyen at ony lime.

In translation, “quintry” means country. And the poem is saying it can rain for six weeks without stopping!

What a grand route Adam chose for driving back to Banchory, by the Correen Hills. He knew I would appreciate the stretching panorama from the top of the Suie at 1200 feet, where bursts of sunshine lit the woods and vast quilt of ripening crops and rolling pastures speckled with sheep and cattle. Then down we went into Donside at Bridge of Alford for the last lap.

Now for the real pleasure

Next day we deliberately chose the poor weather for the pleasure of a day on Broadcairn, so our route was by Ballater to the Spittal of Muick for the shore path that leads to the white waterslide of the Allt an Dubh Loch. Now for the real pleasure, climbing past a big waterfall that comes pouring down from Lochnagar on the right into a corrie contained by some of the finest rock scenery in the Cairngorms. A compelling cliff dominates everything else, Creag-an-Dubh-Loch, running nearly the whole length of the loch shore. The place has a mysterious feel about it, for the Eagle Rock hems the loch in on the north, so that the only way west is by a white waterslide.

It was a long time since I’d been here, and on that occasion we had broken out by climbing the rock face up the edge of the big gully which splits the crag. This great crag was hardly known then, but now it is seen to be in a class of its own. Hamish Maclnnes regards it as providing some of the best rock-climbing in Britain. And I am pleased to say that much of the pioneering of hard ways has been done by Aberdeen boys of the Etchachan club.

We were content to take an easy way by keeping on up the waterfalls of the burn and on to the shoulder leading to the ridge to Broadcairn, invisible in the drizzling mist. From the top a movement of clouds gave us a glimpse of the pale saucer of Loch Esk and the Jock’s Road region at the head of Glen Doll. Then east down the boulders we went, putting up broods of young ptarmigan on the shoulder that leads to the bulldozed Land-Rover track which takes a high line on the steep ridge above Loch Muick.

An invisible world started to open up below us

This is where we got a fair wetting by failing to take warning of an approaching squall which hit us fair and square as we struggled to get waterproof jackets and trousers out of our bags. The storm was providential, for it gave us a rare moment of revelation as the invisible world started to open up below us, first the white threads of cataracts pouring down from hidden Broadcairn and Lochnagar, then the solidifying of dim shapes and black, thrusting rock shoulders towering above the Dubh Loch. It was one of the most thrilling moments Adam and I have had on these hills.

Now the rain was off and the evening was fairing for the easy jog down the shoulder for the stroll along Loch Muick, enjoying the sight of antlered stags and hinds with their spotted calves. Then across the hill came a peregrine, drawing our attention to it by its squeals of alarm as it flew along the rock face where it had nested successfully.

Adam has been monitoring the breeding success of Deeside peregrines for years, and the sight of the bird set him recounting to me a frightening experience when one of these sharpest of fliers dived at him as if to knock off his head.

“I couldn’t help ducking,” he said. “And I have heard that this was how the naturalist Michael Marsland met his death in Perthshire this year when he was up at a nest. The peregrine went for him, and in ducking he lost his balance and fell off the cliff.”

I have never heard of a peregrine carrying home an attack on a human, but the sad lesson is one I shall remember.

Check back next Friday for more from Tom Weir.

- Monach Islands map

- Graham Tiso and Iain Smart look across to the ruins of the crofts on Heisker

- The Buck dominates the countryside near Cabrach

- Map showing Cabrach

- Off to the Monach Islands

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.