Discover the life of Robert Burns, Scotland’s historic Bard

On January 25, 1759, one of Scotland’s favourite sons was born into a world of political upheaval.

Much of Africa and South America had yet to be mapped, Australia had still to be colonised, and the United States Declaration of Independence was still some 17 years away.

Closer to home, Scotland was suffering the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The last pitched battle on British soil saw a bloody defeat for Jacobite forces hoping to reinstate a Catholic king to the British throne.

After the defeat, bagpipes, Gaelic and the wearing of tartan were banned by extensions of the British Government’s Act of Proscription, as was the bearing of arms north of the Highland line. Meanwhile, the Industrial Age was just beginning, and in another 10 years Scottish inventor James Watt would patent the modern steam engine.

A wee serving of Robert Burns trivia to entertain and impress this Burns Night

Entertain assembled guests at a Burns Supper or impress your neighbours at the table with these lesser-known details about the bard.

Top Of The Scots

Robert Burns was voted The Greatest Scot by viewers of Scottish TV (STV) in 2009.

He beat other great Scottish figures, including Sir William Wallace, Sir Alexander Fleming , and King Robert the Bruce.

Worldwide Appeal

A translation of My Heart’s in the Highlands was adopted as the marching song of the Chinese resistance fighters in the Second World War.

Starstruck

In 1985 the International Astronomical Union named a crater on the planet Mercury, Burns, after the bard.

Streets of Fame

More than 720 street names in Britain are named after the poet and there are at least two towns in the US – Burns, New York, and Burns, Oregon.

The train journey between Glasgow and Edinburgh today takes around 45 minutes, but in 1759 the 74km journey (46 miles) took two days on horseback. Alloway, where Burns was born, is roughly 64km (40 miles) south west of Glasgow.

Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. Burns was born here on January 25, 1759 (Shutterstock)

Farming or crofting was the way of life for many 18th-century Scots, and the potato had been introduced to the country as a crop staple only 20 years prior. Robert Burns, the man who would become the Ploughman Poet, the Bard of Ayrshire and finally Scotland’s National Bard began his life on one such farm.

He was born in a tiny, thatched cottage, which his father had built with his own two hands, and spent much of his childhood in the poverty and severe manual labour of a life working the fields.

The hard and sometimes insular farm life broke many a spirit, but seemed to instil in young Robert Burns something else – an understanding of the world around him that would make his poems so universally appreciated.

Burns wrote his first published poem at the tender age of 15, and over the next two decades he would add hundreds more.

His first publication was a collection of poetry, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. The first edition is known as the Kilmarnock edition, and its success in 1786 took Burns to Edinburgh.

This is believed to be the first time the poet had been more than 50km (30 miles) from his birthplace.

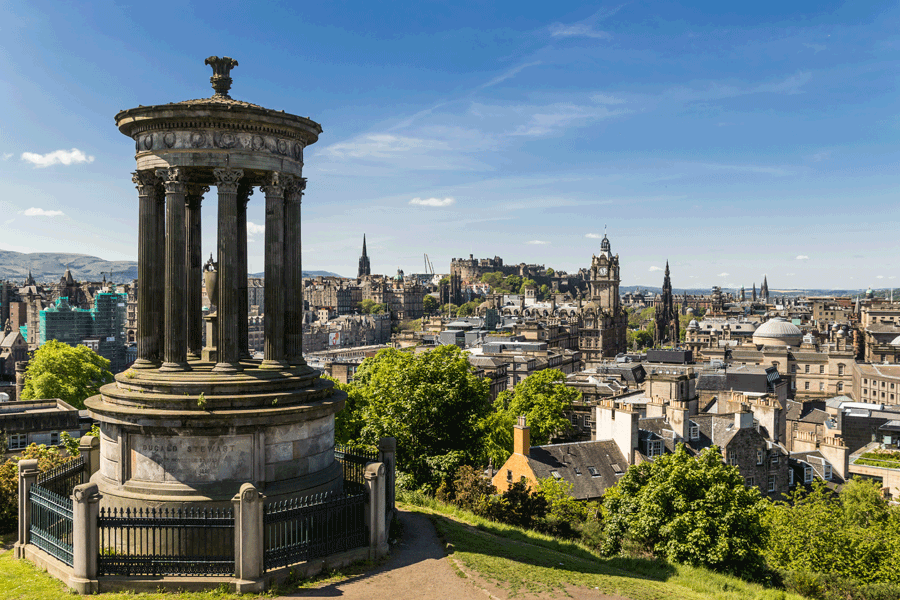

Burns Monument, Edinburgh. The monument was designed by Thomas Hamilton, the foundation stone was laid in 1831 (Shutterstock)

Here, the Edinburgh edition of the collection was printed, bringing the poet fame and fortune for a time, and inspiring other literary greats such as a young Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth, among others.

Sir Walter Scott, himself one of Scotland’s more prominent literary figures, was 16 when he met Burns in Edinburgh, and recalled the meeting in an 1827 letter:

“His person was strong and robust: his manners rustic, not clownish; a sort of dignified plainness and simplicity, which received part of its effect perhaps from one’s knowledge of his extraordinary talents.

“There was a strong expression of sense and shrewdness in all his lineaments; the eye alone, I think, indicated, the poetical character and temperament. It was large, and of a dark cast, and glowed (I say literally glowed) when he spoke with feeling or interest. I never saw such another eye in a human head, though I have seen the most distinguished men in my time.”

Burns certainly had that affect on people. He charmed almost everyone he met – excluding, of course, his father-in-law – and this charm saw him in almost continual trouble, embarking on lover’s trysts in practically every town in Ayrshire.

This charm was never disingenuous – however fleeting. Burns was deeply passionate, and fell in love often – with women, with the landscape that surrounded him, and even with ideas or notions of equality.

He was constantly striving to explore the world outside his home country of Ayrshire, and embarked on several month-long tours around Scotland in 1787 in order to seek new inspiration after the success of his Edinburgh edition.

Burns toured the Borders, the West Highlands and around the north east of Scotland, keeping a journal of local traditions. He was a great collector of songs, and there are a great many traditional Scottish songs which would have been lost to history had the bard not faithfully noted them down.

“Old Scots Songs are, you know, a favourite study and pursuit of mine,” Burns said in a 1790 letter. “There is a certain something in the old Scotch songs, a wild happiness of thought and expression.”

This passion for Scots song extended to Scotland itself. Many of Burns’s poems are shouts of national pride, but Burns was not, strictly speaking, a nationalist poet.

Scots Wha Hae might be a rousing call to arms written as a speech by Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn, but Ye Jacobites, by comparison, is a warning – that the spoils of war are often worth far less than the blood spilled to get them.

4 Famous Robert Burns poems

“Auld Lang Syne”

“Address to a Haggis”

“To a Mouse”

“Tam O’ Shanter”

As his poetry took him around Scotland and Burns learned more of the world outside the Ayrshire farms, his egalitarian views, which first came to him while working the fields, grew stronger.

Burns was an opponent of the monarchy and slavery, and a champion of the rights of man and democracy. He loudly spoke against hypocrisy and the whisky tax, and for conservationism and the French and American revolutions.

The latter lost him many influential and hard-won friends in his later years, but despite Burns’s increasing poverty and ill health in his later life, he refused to let go of his beliefs to appease them.

Throughout Burns’s short life he was plagued by illness – hard farm labour in all weathers had aggravated a pre-existing rheumatic condition and he died tragically young at the age of 37.

Explore Scottish history with The Scots Magazine

Discover chapters of Scottish history with regular contributors and help from our vast archives.

The Scots Magazine is a glossy monthly packed with over 130 entertaining and informative pages exploring Scotland’s places, people and culture. Find out more information here.