Tom Weir | Sailing with the Wind

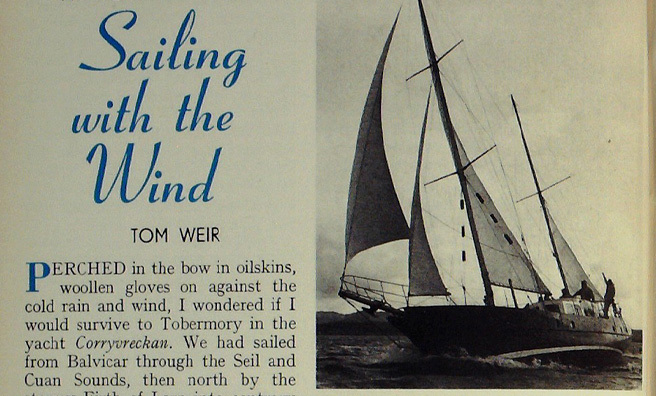

Perched in the bow in oilskins, woollen gloves on against the cold rain and wind, I wondered if I would survive to Tobermory in the yacht Corryvreckan

We had sailed from Balvicar through the Seil and Cuan Sounds, then north by the stormy Firth of Lorn into contrary winds in the gloomy Sound of Mull. The picture of West Coast yachting was different from the one in my mind’s eye when I booked berths for two in the hope of learning something about the art of sailing with the wind.

Not that I was new to sailing. After all, had I not survived the television series “Weir’s Aweigh” without ever being sick, and that on an Outer Hebridean trip which took us from Loch Sween out to Barrahead and Mingulay, returning by Eriskay, the Garvellachs and the Gulf of Corryvreckan? (Read Tom’s account of this trip here)

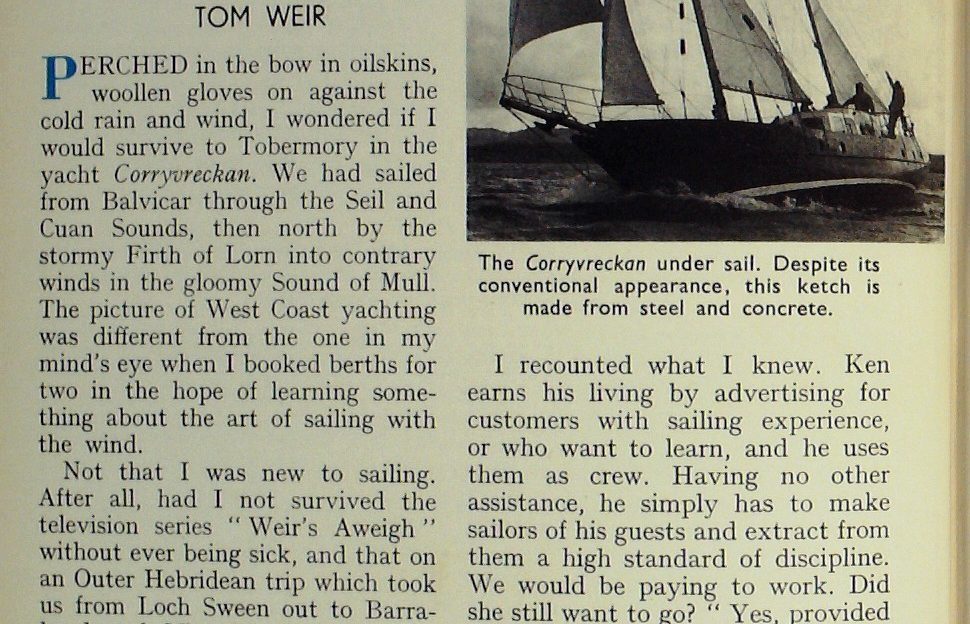

The memory of that long television voyage was all sunshine, which is why I suggested to my wife, who loves the sea, that we might try for a booking on Ken Brown’s 55-foot-long Bermudan ketch Corryvreckan. I had heard that he was an exceptional skipper, adventurous, willing to land you on remote islands, yet with a caution born of long experience although he was only 40 years old.

I recounted what I knew. Ken earns his living by advertising for customers with sailing experience, or who want to learn, and he uses them as crew. Having no other assistance, he simply has to make sailors of his guests and extract from them a high standard of discipline. We would be paying to work. Did she still want to go?

“Yes, provided I can get absolute reassurance that there will be no pop music aboard, for that’s a disease of boats nowadays.”

“I hate it myself,” said Ken when he spoke to us on the phone. “I don’t allow it, any more than I allow smoking below deck.”

So we arrived at Balvicar on a pouring wet night, parked the car to be collected in eight days’ time, and were taken out by rubber dinghy to climb aboard the rather portly green yacht and meet our fellow crew members.

Two were French students, boy and girl; two were from Bath, mother and daughter; there was a young married couple from the Kirkintilloch area, and ourselves. In words of welcome, the bearded skipper told us what was expected of us. He would do all the cooking, but every day a different “watch” of two “would do the galley and cleaning chores. All hands would hoist and lower sails as required. Lunch daily would be sandwiches. Dinner would be made once we were anchored for the night, wherever that might be.

By the time we slid into the welcome shelter of Tobermory Bay and anchored among a host of other yachts we knew the young French pair were our most experienced amateur sailors. Nor were the young Scots couple absolute beginners, so we had a crew of four pretty able seafarers and four determined to take their turn at the wheel, keep the sails tilled with wind, and judge when the time had come to “go-about,” on another tack. All of us were given a bit of practice that first day.

The following morning was gurly with wind and rain, so instead of “anchor aweigh” we had a couple of hours in the busy wee town, seeing the Tiree car ferry arrive, and making the pleasant discovery that I knew a few folk on the pier.

In a torment of white-crested rollers…

Tourists arriving from Ardnamurchan by car ferry told us that it was pretty rough out there, but Ken our skipper decided to sail.

“We can always run for shelter in Loch Sunart if it’s too fierce to go west,” he reasoned.

Once in the open water, though, we kept going, pitching and rolling in a torment of white-crested rollers. Keeping the boat “on compass course” while being toppled off balance in the violent motion was impossible for me, and I knew I didn’t want any sandwiches or soup when the watch of the day served it out. I had to grab a bucket, and found my thoughts fastened on the Isle of Coll where Ken was proposing to seek shelter.

That rocky island seemed a long time in coming, then almost suddenly we were under the land, and the motion was easing as we passed into ever calmer water to anchor among a few other sheltering yachts.

The effect on my moral was good. I now felt ready for my dinner and a walk on the wee hills whose lochs are such a haunt of red-throated divers and Arctic skuas.

The rain had passed, too, by the time we put ashore below the little street of white cottages where half the 140 folk of the island live at the sea head of Loch Eatharna. Boots on, we were soon among the hummocks of Lewisian gneiss and trapped lochans which are so reminiscent of Assynt in Sutherland except that the bird life is richer here because of the nearness of the coast.

It was dusk and a red sunset was fading when we went to the hotel and joined the rest who were having a sing-song with some of the other yachtsmen. The visitors’ book and the names of an incredible number of boats showed just how immensely popular West Coast cruising has become.

Sunshine vied with showers when we sailed away from Coll and headed for the Treshnish Islands with a favourable wind hoping to make a landing, moving at eight knots, with the Dutchman’s Cap creeping perceptibly as we wafted along. I feared the skipper would turn away from these difficult skerries as he took the wheel from me and nosed his way into Lunga and ran down the anchor.

It was Lunga where Sir Frank Fraser Darling camped in the 1930’s when he began his pioneering work on seabirds and seals. Having tried several times to reach it and failed, it was a great moment for me to leap eagerly from the dinghy to the beach where the stormy petrels nest.

The best bird rock in the Hebrides

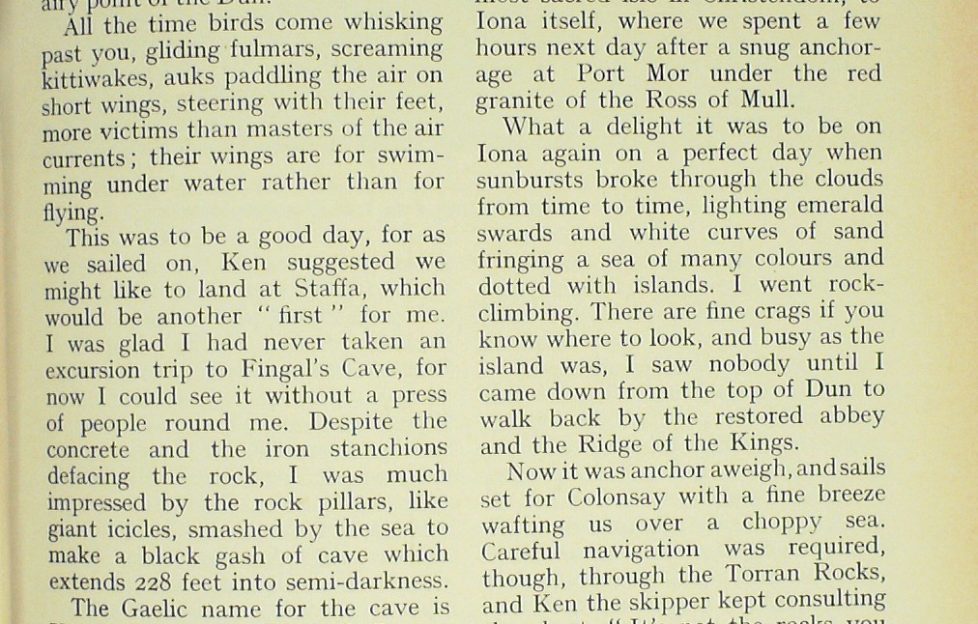

I can claim personal experience of most of the bird rocks of the Hebrides and the Northern Isles, but I’ve seen none better than the unclimbed pinnacle of Dun Cruit, which is separated from Lunga by a narrow canyon of slunging sea, echoing with the cries of seabirds. You sit, as it were, in the dress circle, with tiers of guillemots, kittiwakes, puffins and razorbills reaching to the airy point of the Dun.

All the time birds come whisking past you, gliding fulmars, screaming kittiwakes, auks paddling the air on short wings, steering with their feet, more victims than masters of the air currents; their wings are for swimming under water rather than for flying.

This was to be a good day, for as we sailed on, Ken suggested we might like to land at Staffa, which would be another “first” for me. I was glad I had never taken an excursion trip to Fingal’s Cave, for now I could see it without a press of people round me.

Despite the concrete and the iron stanchions defacing the rock, I was much impressed by the rock pillars, like giant icicles, smashed by the sea to make a black gash of cave which extends 228 feet into semi-darkness.

The Gaelic name for the cave is Uamh Binne—the Musical Cave— which distinguishes it from neighbouring caves. The music is caused by the waves tinkling over the broken-off pillars of lava, each of hexagonal shape where the hot material cooled at the joints. The composer Mendelssohn visited it in 1829 and described it to music in his famous Hebridean Overture, popularly known as “Fingal’s Cave.”

What nobody had told me, however, was that from the darkness at the very back of the cave you look out as through a telescope to the most sacred isle in Christendom, to Iona itself, where we spent a few hours next day after a snug anchorage at Port Mor under the red granite of the Ross of Mull.

What a delight it was to be on Iona again on a perfect day when sunbursts broke through the clouds from time to time, lighting emerald swards and white curves of sand fringing a sea of many colours and dotted with islands. I went rock- climbing. There are fine crags if you know where to look, and busy as the island was, I saw nobody until I came down from the top of Dun to walk back by the restored abbey and the Ridge of the Kings.

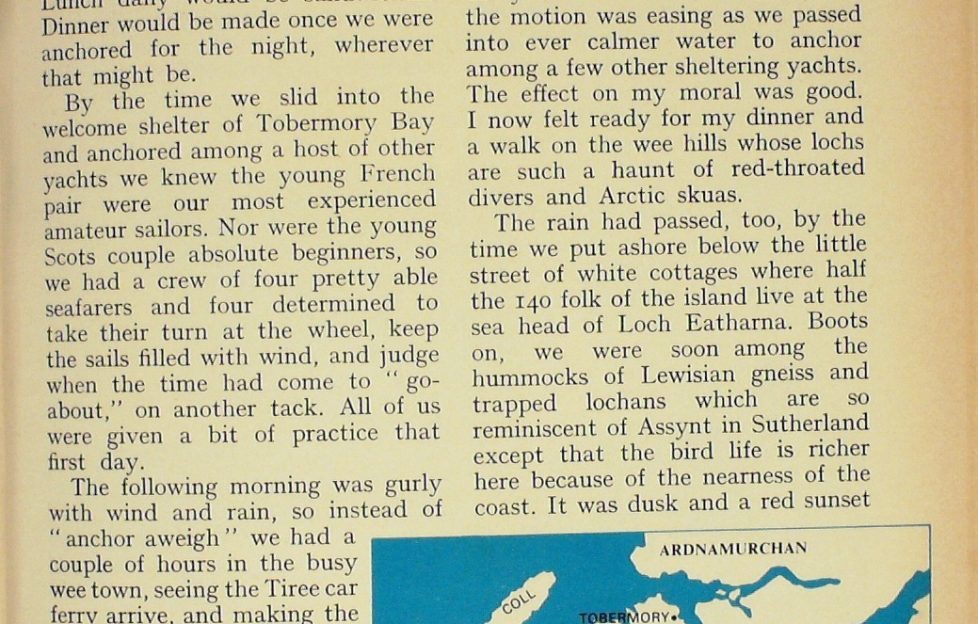

Now it was anchor aweigh, and sails set for Colonsay with a line breeze wafting us over a choppy sea. Careful navigation was required, though, through the Torran Rocks, and Ken the skipper kept consulting the chart.

“It’s not the rocks you see but the ones which are just below the surface that are the danger.”

Birds were good; stormy petrels fluttering over the waves, only half the size of blackbirds, with white rumps, and two sooty shearwaters, brown vagrants of the Southern ocean, larger than the common Manx.

We had shaken down into an efficient crew by this time and learned a good deal about the boat, and about its master.

A dream of sailing

Ken Brown, a marine engineer for eight years, had begun his present way of life by chartering a boat for three years. He met his school teacher wife on one of his trips and they dreamed up a scheme. She would teach to keep the home going, while he built a boat which could be their future home, and they would cruise the West Coast together with paying guests as crew.

Ken had two original ideas. He would build a boat using ferro-cement instead of wood or fibre-glass, and he would build it in a Dunfermline garden. He got his information from books. Concrete boats are used with success in New Zealand, so why not here? The framework would be tubular steel welded and covered by steel bars like lattice work, and in the 3-and-a-half years it took before it was ready for the water, it proved a big puzzle to passers-by, with eight layers of wire mesh and thousands of wire ties.

All this had to be covered with concrete, so Ken laid in 10 tons of sand, 65 bags of cement, a barrel of beer, 36 pairs of leather gloves, and got down to it with 30 friends and six professional plasterers.

The joinery work—floorboards, bunks, lockers, doors, cabin, deck-house— was all done by Ken. Deck fittings he made out of scrap galvanised metal. With her ten tons of steel and ten tons of concrete, the boat had to be lifted over a garden hedge by crane on to a low- loader and taken ten miles to be launched at Burntisland. He told me:

“I made it roomy, thinking it would be our home, but by the time the boat was built we had a family and it was not practicable. First trip was Easter 1972. The weather was bad, but there were almost no teething troubles, so my 3-and-a-half years of non-paid labour had paid off, for I had a floating yacht that worked. In fact, I had a panic to complete the boat and make her ready for the first customers, two teachers and seven kids from England. The first season was fairly good. The second was booked solid. In our six years on the boat things have worked out pretty well.”

We talked about the future.

“I don’t see myself doing anything else. It’s an enjoyable life, and 25 per cent of my customers come back. It’s a bit tough on the family, though, because I’m away all summer, but I’m never more than twelve days without a night at home. I don’t get bored, because every trip is different—weather, the places we go, and the folk who make your crew. There’s no generation gap aboard a boat, and I’m glad to say that most who come are not too bothered by seasickness. Sometimes we go as far as St Kilda.”

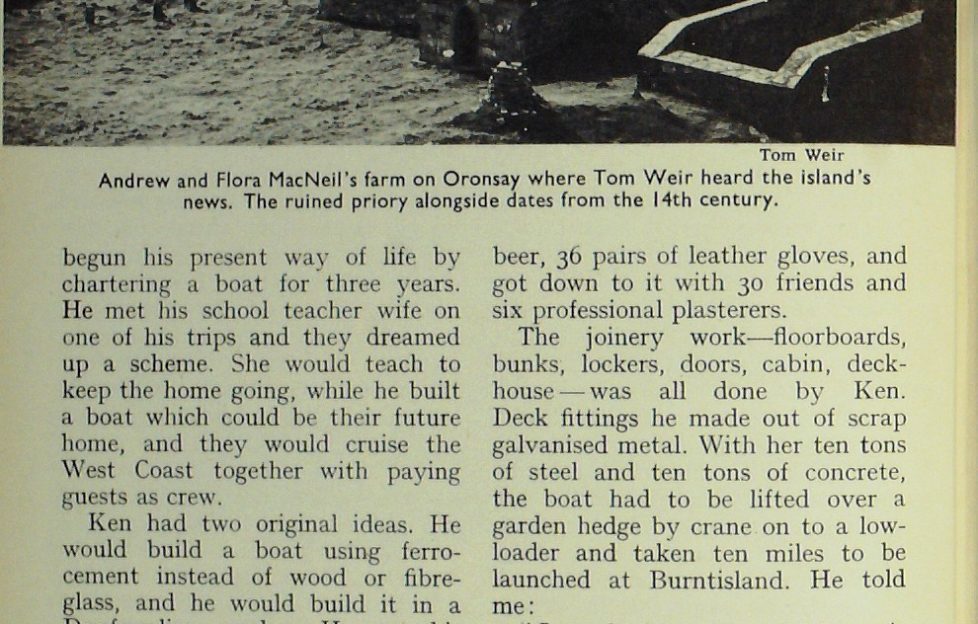

Personally, I was glad we were only going as far as Colonsay, and was happy to see the raised beaches of its west coast and come down round Oronsay to anchor among the screaming terns near Seal Cottage, a place that felt almost home to me since this tidal island is farmed by Andrew and Flora MacNeil and many a visit I have made to them. So it was good to go ashore and walk across the rabbit-infested sward, listening to familiar sounds of mewing buzzards and seeing bobbing wheatears and stonechats along the dry-stone walls.

I met up with Andrew as I came out of the priory ruins which date from 1380, but are on a site dating back to St Columba’s time, for he landed here before sailing north to Iona to found his Mission Church. Andrew’s farm steadings incorporate priory stones in their walls— an act of vandalism not perpetrated by him.

Flora got a surprise when I walked into her kitchen, and it was fine to hear the Oronsay news over tea and warm pancakes. The island has a new laird now, Lord Strathcona having sold it as a separate lot, and perhaps by the time this article appears in print Colonsay will have been sold for the £ 1 million which is being asked for it.

“We are not affected,” said Flora, ” but poor Colonsay—nobody knows what’s going to happen.”

Sir Frank Fraser Darling spoke truth in his West Highland Survey published 23 years ago when he wrote with such perception :

” Colonsay, though considerably larger than Canna and Muck, is in the same social state of being held together by an honoured and valued proprietor. If interest and means were to fail, the existence of Colonsay as a self-contained, dynamic unit would be precarious.”

The means failed with the death of old Lord Strathcona, and the son has to sell the island because he has not the means to subsidise the economy as his father did. The question is, can another benefactor be found, or will another way of life have to be found for the island?

It was to another declining island we set sail by turning down the Sound of Islay to round Jura and tuck in for a windy night in Lowlandman’s Bay as down-draughts from the Paps rocked us on our last night aboard. It had been a brisk, exhilarating sail, and darkness was falling by the time we had eaten dinner so there was no time to go ashore.

The morning, alas, was disappointingly calm for the northward sail by Scarba and Luing to arrive back at Balvicar and tie up at the mooring buoy on Friday afternoon.

Personally, I was glad not to be heading out to sea with the next crew, though my wife would happily have settled for St Kilda in the Corryvreckan. But, then, her father was a sea captain. Mine was the son of a farmer.

This column from Tom Weir was first published in May, 1978.

Look out for his June column, In Border Country, published online next Friday.

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here for Tom’s online archives.