Tom Weir | A Welcome To The Hills

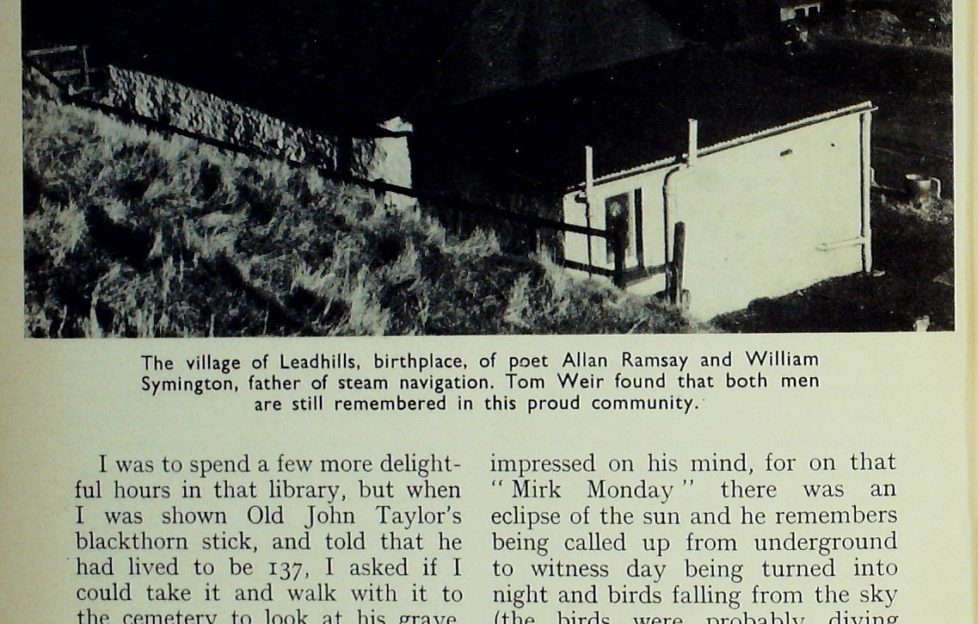

In the highest village in Scotland Tom Weir explores its mining culture and remarkable engineering sons

In the warm light of the mid-morning sun the Nith Valley was looking better than I had ever seen it, with fields curving on each side of the river and sleek cattle dotting them, bright as in a painting. I was comparing it in my mind to the Kentish downlands until the high ridges of the Lowthers heaved above Sanquhar, and gone was my tranquillity.

I had to get up there, and before me was the Mennock Pass, seven miles of magic climbing from the beauty of a man-made landscape into brown heather hills, closing in to a trench with snow under my wheels, and round a corner, Wanlockhead, the highest village in Scotland looking like something out of Switzerland.

The strung-out village houses on each side of the burn lie just below the 1500-ft. summit of the pass, with a branch road leading to the billiard-ball radar domes occupying the top of Lowther Hill, 2377 ft.

Long Memories in the Hills

Twenty years ago a party of us had used that road to begin a February ski tour over Green Lowther and down the ridge of Windy Knoll to Leadhills, but I didn’t expect to be remembered when I met the shepherd, Jake Elliot, out with his dogs, but ” Aye,” he said, ” it was jist up there I met ye the last time. There no sae muckle skiing done here noo.”

Jake’s house above Leadhills is on par with the top-most in Wanlockhead, and I was soon in the snuggery of the fireside, reslisting an invitation to have a cup of tea, but enjoying a chat with this Ettrick shepherd and his wife, who is a local lass and went to school in Leadhills. I told them I couldn’t stop for now, but I was going to come back for a week and get to know something about this country side of which they are both so fond.

And back I went a week or two later to make good my promise, to walk immediately into another coincidental meeting when I knocked at the door of a house to ask for information. You are never kept on a doorstep in Leadhills, and before I had asked my question I was inside and seated at the fireside in a cosy wee room and invited to have a cup of coffee by the smiling old lady who was saying that the last time I was in the house was when her brother was occupant.

I immediately felt an impostor. She is mistaking me for somebody else, I was thinking, when she cleared up the matter by saying, ” You brought your mother here once with Mrs Hamilton and her daughter Mary when they lived next door to you in Glasgow.”

Now I remembered. They were Leadhills folk, and when I bought my first motor car in the mid-fifties we made an outing which my mother never forgot. That wee cottage made a powerful impression.

The First Miners’ Library

Life keeps catching up with you. I now had the perfect introduction to a lot of folk in Leadhills, and when I said I would like to spend an hour or two in the Miners’ Library I was touched to find that four of its committee—Mrs Cameron, Mrs Kay, Miss Holly and Mrs Smith had the place warmed up, a fire going and tea and sandwiches for me, assisting me at the same time to find books and information I wanted. The ladies were proud of their library founded by the miners in 1741, and the first of its kind in Britain. It was the miners’ hard-earned money which bought the books.

One of the ladies told me, “It’s called the Allan Ramsay Memorial Library after the Leadhills poet who wrote The Gentle Shepherd, but there’s no doubt that the mine manager, James Stirling, had a lot to do with it. He provided some of his own books, and the reading-room. But the idea maybe came from Allan Ramsay, who set up the first circulating library in Britain at the Luckenbooths in Edinburgh. James Stirling, curiously enough, is of the same family who set up the Stirling Library in Glasgow.”

I was to hear a lot about James Stirling—known as the Venetian— who became mine manager at Leadhills in 1734, and as a social reformer pre-dates David Dale and Robert Owen at New Lanark.

Stirling took over the mine when it was losing money and in a bad way. His own fortunes were none too good, for he had been thrown out of Italy for trying to uncover the secrets of Venetian glass-making so that he could bring them home and set up in competition. His life would have been in university circles, for he was a noted mathematician and scholar, but this was denied him because he had the unwelcome taint of Jacobite attached to him.

Stirling was 43 years of age when he came to Leadhills to try out a job for which he had no training. He made his influence felt from the very beginning by appointing the best men he could find as overseers and working out a system of bookkeeping based on piece-work bargains with the men. We would call them productivity agreements now.

He also cut the hours of any shift to six, and drew up sensible rules and safety regulations. Always he was concerned for the welfare of the miners, for whose intelligence he had great respect.

“These are the bargain books,” said Mrs Kay, unlocking a special case containing dozens of large ledgers containing the entries of the overseers. To my surprise, I kept coming across my own name, for one of the writers was a Thomas Weir, who detailed his visits to the various lead veins and measurements of progress. Another Tom Weir was a notable gold-finder.

Research in the Miners’ Library revealed that as early as 1260, the monks of Newbattle Abbey were lead mining in these parts, but that big scale developments did not get off the ground until 1640.

Progress must have been swift, for Thomas Pennant, visiting the high villages on his famous “Tour,” describes the mines as “inexhaustible” in 1772. But he was not enchanted by what he saw — a population of 1500 souls living in what he describes as mean houses in gloomy surroundings, “with neither tree nor shrub, nor verdure, nor picturesque rock, to amuse the eye.” The workforce then was 500.

Old John Taylor

I was to spend a few more delightful hours in that library, but when I was shown Old John Taylor’s blackthorn stick, and told that he had lived to be 137, I asked if I could take it and walk with it to the cemetery to look at his grave.

The recumbent slab tells us he died in 1770, but of his birth in Cumberland there is no record. What is known, however, is that he was an old man when he came from Strontian to work in Leadhills in 1732. The question is, was he 95? The folk around here believe he was, and that he was a mere 133 when he died and not 137.

The evidence on which this is based comes down directly from Old John, who had the date 1652 impressed on his mind, for on that “Mirk Monday” there was an eclipse of the sun and he remembers being called up from underground to witness day being turned into night and birds falling from the sky (the birds were probably diving down to roost, being fooled by the sudden darkness)

To have been underground and working as a miner John must have been over 15, the minimum age for underground work at that time.

The chronology of his life squares with this, for he travelled widely, working in various lead mines, prospecting in Ettrick, in Islay, at Strontian, where he contracted scurvy because of the monotonous diet of salt beef and whisky ; he even worked in the Royal Mint in Edinburgh, converting Scottish coin to English.

By reason of this wide experience he was a self-taught mining engineer when he came to Leadhills. Astonishingly he still had 32 years of working life left in him.

He was 5 ft. 8 ins. tall, a spare man with a ruddy complexion, and he said his teeth fell out when he stopped chewing tobacco, though it was more likely due to scurvy. He could eat at any time of day or night, and one story shows his exceptional hardiness and spirit.

Out fishing in the hills, and following up two burns after trout, he got caught out in a blizzard and failed to make it home. The curfew bell was rung, a search party went out and found him in the snow, still alive.

As soon as he recovered he was away back to the hill to recover his rod, which he had left upright to be sure of finding it again. He was 116 at the time.

Senility came to him in the end. In winter he felt the cold and would stay in bed, taking a wee glass of brandy to warm his stomach. But four years before he gave up the ghost he walked the two-mile gradient from his cottage to visit his children and grandchildren, and then walked home again.

John Taylor’s grave is just over the wall from the Symington monument, commemorating another great son of Leadhills, born in 1764, son of a mine manager who put his talents to use here on steam pumps before turning his mind to ships and steam navigation. And one who helped him greatly to realise his ambition was a grandson of Old John Taylor, university-trained and tutor to the children of Patrick Miller of Dalswinton, who became Symington’s patron.

Success attended their partnership on Dalswinton Loch in October 1788 when the first working steamboat took the water, watched by a big crowd among whom was Rabbie Burns, who was farming at Ellisland nearby, at that time.

The Father of Steamships

The practical steamship on which the engineering reputation of Symington rests had to wait for a bit while the inventor put his skills to use inventing new steam pumps for Wanlockhead and other mines. The Charlotte Dimdas was named after his new sponsor, and made its debut on the Forth and Clyde Canal in January 1803. This was a steamship which did its job perfectly, towing barges efficiently and speedily. But there was prejudice. The canal shareholders feared that the water disturbance caused by the paddles would erode the banks and the boat was never used for anything except dredging—and without its engine.

Symington, alas, was no business man. Nor did he have that magical ingredient—luck. Henry Bell and Robert Fulton in America operated the first commercially successful steamships. Symington didn’t even get the state pension he hoped for. All he got for his discovery was the sum of £150, and he died a poor man at the age of 67. His greatness lives on.

Now I moved up to Wanlockhead, and had the good luck to meet industrial archaeologist Mr Geoff Downs Rose, one of the leading lights of the Wanlockhead Museum Trust. He gave me a conducted tour of the walkway which has been devised to show visitors the layout of the village in relation to the mines. It proved so popular last summer that the little pamphlet and map which goes with it were sold out.

First we looked at the museum in a wee cottage of Gold Scars Row, containing just the right amount of stuff, a model showing the veins at different levels inside the hills which penetrate to a depth of 600 fathoms, good graphic stuff, with wee figures of miners at different levels, giving it scale. A constant problem of working underground was flooding, so there is a working model of a beam-engine showing how the early engineers used water from above to pump out water below ground by the use of aqueducts and buckets.

The minerals, in the form of silver, lead and gold, and the tools used to extract them, are all here, together with photographs of great historical interest. Next we visited the library, founded in 1756 as a reading society like that in Leadhills, and then in process of having its thousands of books re-catalogued by Job Creation girls.

And we had a look at the very first school, built in 1750 and a scheduled building. It is now a thriving community centre, and will double-up as an outdoor centre in summer. Farther down we came to the mine workings and went underground—crawling 400 yards inside the hill by torchlight, following the dank twists and turns of a rock passage blasted out of the hill by gunpowder and cleared every inch of the way by shovel.

It was good to straighten up and breathe fresh air again after an hour inside. We had a look at the smelt mill, where Job Creation men and boys were restoring the foundations to show ore hearths and the water-wheel pit. I wanted to talk to some old miners, and was introduced to Joe Scott, who took me to see his father and his Uncle Wull, who had begun together in the Wanlock mine at the age of 16.

Sanny Scott, who is now nearly 80, described the work in one vehement word, “Slavery!” I wish I could write his pure Scots Doric, but I can’t.

“What else was it?” he demanded of Wull rhetorically. “You even had to buy your own gunpowder, blasting, shovelling, hauling, hard, dangerous work for 27s 6d a week, and on constant shift system, day and night.”

Wull nodded his assent.

“So you’ve no good word to say for it at all?” I asked. “What about comradeship?”

“Aye,” he said, his face lighting up, “there was plenty of that. In the mine you had to depend on your mates. You worked as a team of six, and you were on a piece-work bargain so you had to pull your weight. There was always danger, and you had to trust one another and depend on each other.”

“What about Wanlockhead as a place to live?” I asked them.

“There’s no place like it,” they both agreed. “You’re never lonely, and you never weary. We’ve a club. There’s always something going on, even if it’s only the weather. You can be in the clouds and you can be above them in this place. We had a great time when we were young, quoiting, fishing, curling, looking for gold in the burns, wandering the hills.”

Sanny’s son Joe shares his enthusiasm for living in Wanlockhead although there are snags.

“We’ve no school in the village now. My son goes to Leadhills, and there’s not much in the way of work. Most of the people in the two villages commute by car to their jobs. I’m lucky — I work at the Radar Station. It’s great to be back here for I was a long time away at various jobs, some of them in Glasgow. My wife’s from Cambuslang but she’d far rather live here.”

We went up to the Radar Station to look on what Joe regards as the finest view in Scotland, down the narrows of the Enterkin Pass to the Nith.

“The Deil’s Chair — that’s where I’d like to take you. Do you know its story?”

I didn’t.

“Well, you know about the Covenanters. This was a hot-bed of them, and they were determined to rescue a minister by the name of Mr Welch who was being taken from Dumfries jail to Edinburgh for trial. In these days of the 17th century, the three ways across the Lowthers were by the Dalveen, the Mennockand the Enterkin Passes, so the Covenanters had to watch all of then since they didn’t know which one the dragoons would use.

“It fell to the Enterkin lads to carry out the rescue just above that very narrow bit you can see from here, where the hills squeeze down on the burn. The mist was in their favour that day. They could hear the dragoons but couldn’t be seen and they took the troops by surprise, ordering them to give up their prisoners. The officer refused, but changed his mind when a shot sent a man and horse into the ravine. The Guard of 28 gave up nine prisoners, and I can just imagine it all when I am down there.”

I had the pleasure of going back there in the conditions that Joe likes best, when the hilltops stand above the clouds, and that day as I dropped down from the Pass towards the Nith it was like being above a polar sea flooding everything to the south while the northern side was clear and brilliant — the hills on each side of Beattock, with the Annan on one side and the Clyde on the other.

Tom Weir stays in this area to trace the true source of the Clyde in the next column from his archives, which goes live next Friday.

- This massive beam engine – now a scheduled historical monument – used to draw water out of a mine. Day 9 of the Southern Upland Way blogged about at http://ramblingman.org.uk/southernuplandway/day9

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here for Tom’s online archives.