Tom Weir | Scotland In Miniature

Returning to the isle he worked the harvest fields on before the war, Tom Weir delighted in the fascinating history – and future – of Arran in 1978

“A fine day to be sailing to Arran,” I said to Skipper Roddy Murray at Ardrossan. He nodded. “You’ve struck it lucky— it’s been a difficult winter for getting in and out of Ardrossan, with a lot of disruption to the service.”

Roddy is a Lewisman, and I wanted to ask him about the Caledonia which is unpopular with the islanders who regard it as inadequate.

“I hear that some folk want a purpose-built boat specially designed for the Arran run in summer and winter,” I said. “What kind of boat would it be?”

“Well,” he said, “you have big container lorries going over, so you need a ship with high sides. The Caledonia is a good sea boat. We can cross that stretch of water almost any time. Brodick can be difficult for landing at times, but it doesn’t take much of a wind to make Ardrossan dangerous for a ship of this kind.”

He went on, “I want to see the islanders of Arran get the reliable service they desire, but they won’t get it until they have a terminal on some other bit of the Ayrshire coast. They chose Ardrossan because it’s the nearest point to Arran and is fifteen minutes shorter than the crossing from Fairlie. It’s impossible to provide a reliable service in the kind of vessel needed for the Arran run until a suitable terminal is found. It’s as simple as that.”

white-washed cottages gleaming like quartz pebbles…

The sailing time to Arran is only an hour, and it seemed almost too short on that morning of calm blue sea. I was eager to drive ashore and take the road north to Corrie, with its white-washed cottages gleaming like quartz pebbles above the pink sandstone of the little harbour. Mist was still clinging to the top of Goat Fell as I took the delightful path that winds up to High Corrie—the only complete clachan left in Arran.

Perched on a shelf among the rigs where the folk cultivated their unfenced patches of oats, barley, peas and potatoes, the white cottages perfectly match each other, and in the highest to the north of the cobbled street lives the distinguished playwright and author, Robert McLellan, who soon had me inside for a cup of coffee in the almost unaltered wee house.

“It had a sail when I came here first forty years ago — a tarred sail for a roof. That’s how the fisherfolk used up their old sails. Mine was the last to go. It’s a picturesque spot, famous among artists. Jessie M. King used to run summer schools here and they lived in these cottages. This clachan was run as a communal farm, producing food for them. Small black cows would be kept outside the field dyke most likely, with a few sheep. The only exports would be surplus cattle and horses. Peat for fuel was just to hand above us. The women would spin the flax and the wool to be made into cloth by the handloom weavers.”

While we talked and strolled on the traces of the old rigs, Goat Fell had thrown the mist from its snowy top. The rock prong of Cioch na-h Oighe was glowing softly grey above the boulder-peppered lower slopes.

A vision of beauty

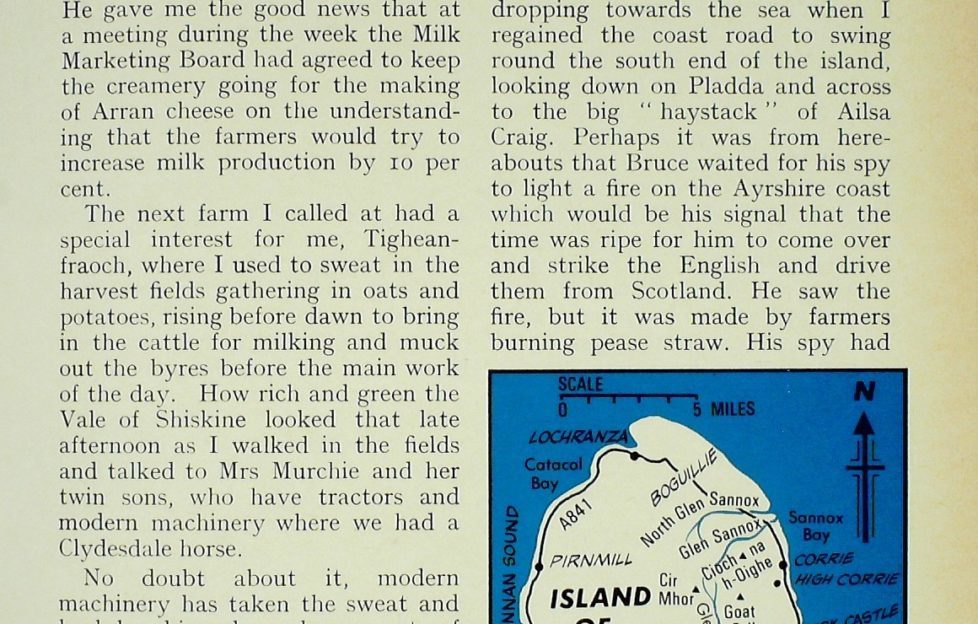

I took a walk up Glen Sannox past the derelict barytes mine for the vision of Cir Mhor and the Witch’s Step rock-sharp against the green sky. And I paid a visit to a favourite camp spot at North Sannox Bay, now an official picnic site with new road and toilets.

To drive north from here by road you have to go inland, over the moorland called the Boguillie, which rises to over 600 feet under the northern peaks, a sunny rise dipping into shadow and icy road on the descent to Lochranza. I had not realised until this December day that this former fishing village with its 16th century castle gets its only glimpse of winter sunshine on its far shore.

“Aye, but we don’t get the wind that the other side gets, and that’s a blessing.”

Certainly it is a good anchorage, and I was told that in the big gales of November it had held as many as three dozen fishing boats seeking shelter. Once important as a herring-fishing village, its houses are largely holiday homes now, unoccupied in winter.

Round the corner in the sunshine at Catacol Bay, I took a seat to enjoy the glass calm of the Kilbrannan Sound and put the binoculars on the birds dotting it. Even without looking you could hear the soft cooing of the black and white eider drakes. Among the widely-spaced cormorants I picked out the birds I had hoped to see, the long, low shapes of great northern divers, and the slimmer red-throats, both species in muted tones of grey and black. Fine to hear the skirl of curlews and the chuckling of turn-stones on the seaweed below me.

I got to know this west side of Arran very well when I lived at Shiskine in the summer of 1939, so it was good to drift down by Thundergay—the name is derived from Tor-na-Gaoith—and Pirnmill, which used to manufacture bobbins for sending to the Ayrshire mills. The old mill is a tenement of flats now, looking out on the Kintyre coast only three and a half miles away.

At Machrie Bay I swung east to Machrie Farm for a chat to Donald McNiven to hear how things were going, for I had heard that the island creamery was under threat of closure because too many farmers were going out of milk production. He gave me the good news that at a meeting during the week the Milk Marketing Board had agreed to keep the creamery going for the making of Arran cheese on the understanding that the farmers would try to increase milk production by 10 per cent.

Tom the Farmer

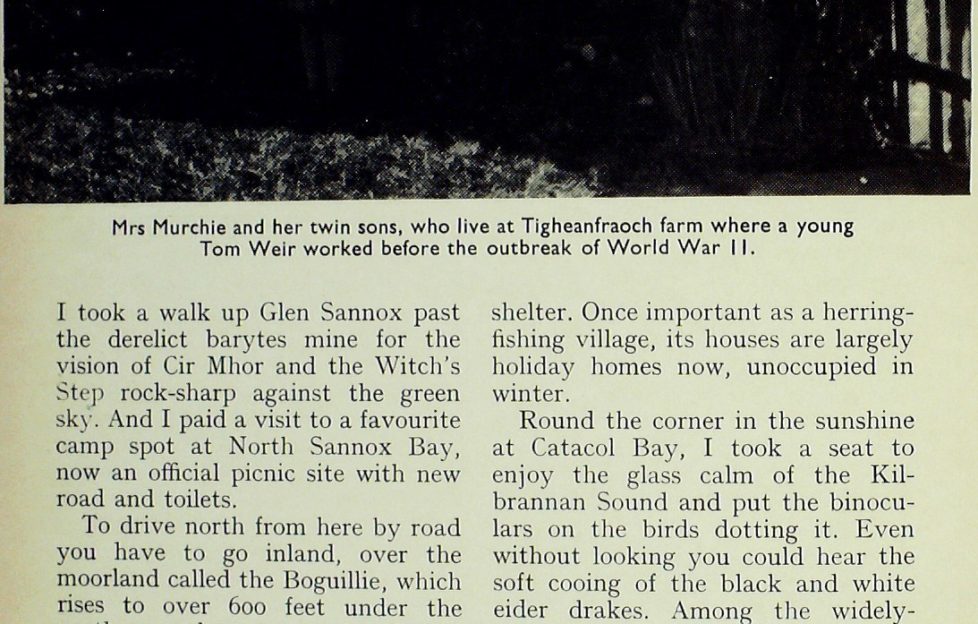

The next farm I called at had a special interest for me, Tighean-fraoch, where I used to sweat in the harvest fields gathering in oats and potatoes, rising before dawn to bring in the cattle for milking and muck out the byres before the main work of the day. How rich and green the Vale of Shiskine looked that late afternoon as I walked in the fields and talked to Mrs Murchie and her twin sons, who have tractors and modern machinery where we had a Clydesdale horse.

No doubt about it, modern machinery has taken the sweat and back-breaking long hours out of farming. My wage in those days was 15s, plus my keep, and Mrs Murchie took me upstairs to show me the tiny boxroom where I used to sleep until the dreaded cry of “Tom!” floated up the stair. It was in the field just outside that I heard that war with Germany had been declared.

Because I registered for service in Arran, I was called up to the Ayrshire Yeomanry.

Tigheanfraoch was a mere 50 acres then and mostly arable. Today it is double the size and the emphasis is on grass for milk, beef and the breeding of sheep. The famous Arran potatoes are a thing of the past.

But holiday visitors still play a big part in the economy of the farm. Come the tourist season, Mrs Murchie and her family move into a wee back house adjoining the stable, and the two farm houses which face each other across the yard are let to families who come year after year.

The red ball of the sun was dropping towards the sea when I regained the coast road to swing round the south end of the island, looking down on Pladda and across to the big “haystack” of Ailsa Craig.

A Mistaken Invasion

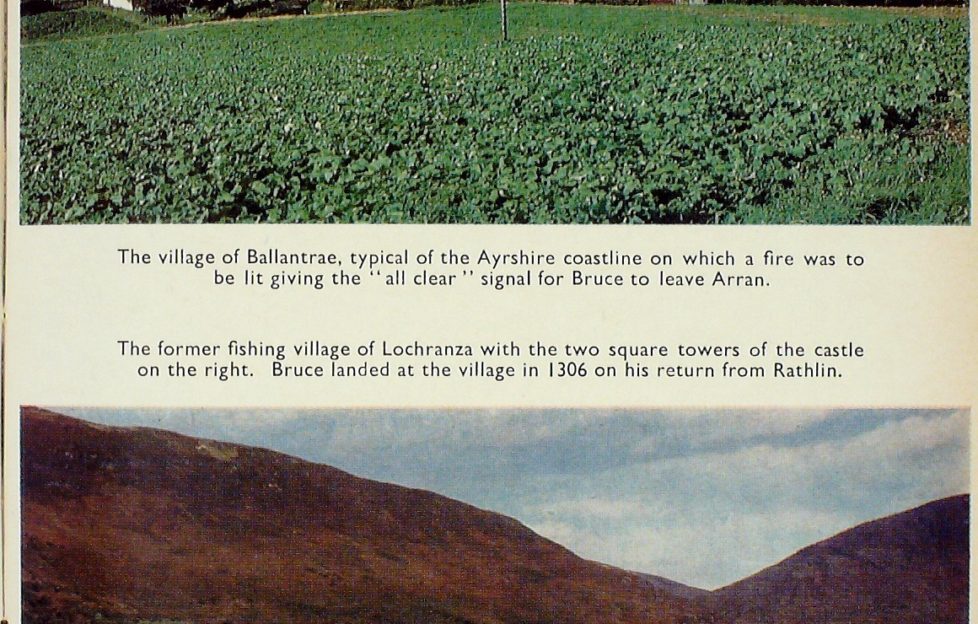

Perhaps it was from here-abouts that Bruce waited for his spy to light a fire on the Ayrshire coast which would be his signal that the time was ripe for him to come over and strike the English and drive them from Scotland.

He saw the fire, but it was made by farmers burning pease straw. His spy had judged the situation to be too dangerous, and for Bruce, answering the false signal, the next few months were his most perilous time, since all the castles were in enemy hands.

I felt close to these events of 670 years ago, for just before coming to Arran I had been at Turnberry, and had been thinking of Bruce setting out with his galleys from Kingscross Point to try, try, try again and win with his desperate men against long odds. And soon I had Kingscross below me and Holy Island blocking the big curve of Lamlash Bay in a shapely ridge soaring to a thousand feet.

The old name for Lamlash is Loch an Eilan, which became Eilean Molaise before the Gaelic was corrupted to Lamlash. The island of the seventh-century Celtic St Molas now belongs to the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, and beneath its peak King Haakon assembled his fleet before and after the Battle of Largs, which was to be disastrous for the Vikings in that battle of 1263.

Although it is Brodick Bay and Drumadoon Bay which give Arran its kidney shape, Lamlash Bay is more of a loch than the others, tapering, as it does, more deeply into the hills. Swinging down to it, I took the shore road to find Dr Horace Pairhurst, archaeologist, formerly senior lecturer in Glasgow University, who has retired here with his Arran wife.

It was good to see them both again and hear over tea how well things have been going with the Isle of Arran Museum Trust since the acquisition of the Old Smiddy at the Rosa Burn and the adjoining stable block.

“We’ve been shoeing horses all summer to let visitors see how the old blacksmiths worked, using hand bellows and home-made tools. You must come and see it before you go, and all the better if there’s a horse to be shod.”

And thanks to the Museum Trust it was made possible, and I had the treat of seeing Willie McKinley of Cumnock, a farm-worker who went into forestry in Arran and was forced to begin shoeing his own horses because there was no blacksmith. Now, with the growth of pony-trekking, he travels all over the island to work at his craft.

For this demonstration Mrs Pauline Muir, tourist officer, provided the horse, for she is a keen rider and her mount needed to be re-shod. As Willie poured a bottle of diesel oil on the pearl coal and a boy pumped the handle of the bellows, he explained that every-thing here was home-made—the tongs, the nippers and the various hand implements.

“The shoe is made of mild steel, bent from a concave bar, and you shape it to fit the horse’s foot. So to shape it, cut it to size and work it, you have to strike while the iron’s hot. You see how the smoke burns off the hoof when I press the shoe home. The horse doesn’t feel anything, for the wall of the hoof is insensitive. Look at these nails— they’re nearly 2 inches inches long. I batter them through, and they come out the other side so that I can clench them over and cut the ends off. If I were to make a mistake and go into the soft part of the hoof it would be as painful for the horse as somebody driving a nail into your own foot.”

The Beginnings of Arran Heritage Museum

The dream to acquire a museum began about 20 years ago, and now that the smiddy is in operation the next thing is to furnish the adjoining buildings to display the old way of life of the island, and set up an archive of books and papers covering every aspect of Arran life, past and present. In the stable block there will be a lecture room for slide shows, which, together with the present Nature Centre, will be a powerful attraction to visitors.

Nor was it done by merely dreaming. Money-raising activities such as whist drives and dances were constant, and Cunninghame District Council acted handsomely by giving a generous grant which enabled the Museum Trust to acquire the smiddy when it became available. I have always been impressed by the fact that facilities offered to tourists in Arran have arisen as a natural growth through the initiative of the islanders.

Mine hostess in Brodick, Mrs Grace Small, is Chairman of the Isle of Arran Tourist Association, but after running a big hotel she and her husband Verner have moved into a small place because they are both keen on the hills and want more time on the high tops. Indeed, while I was ambling about the low ground talking to friends and en-joying the birds of the shore, they were up on the ridges, traversing from Goat Fell over the icy Stacach to Cioch na-h Oighe.

At the Tourist Association’s A.G.M. which preceded the lecture I had come to give them I was surprised to hear that Arran had not done as well as usual in the 1977 tourist season. Questions were being asked why, when more money is being poured into publicity than ever before. Of course, with the recession, it is hard to put a finger on the cause.

Asked to state my own views, I gave it as my opinion that Arran is providing what the people who come here year after year want, the simple pleasures of a marvellously varied island which could be described as a miniature of the best of Scotland, with Highlands to the north and Lowlands to the south, all encompassed by a ring road of 60 miles and a Highland Line across its middle in the String Road between Brodick and Blackwater- foot.

I gave it as my opinion that they should resist outside developers with big-money, Aviemore – Centre – type ideas. I said they should also resist any mineral explorations such as uranium extracting. For it happens that they are in one of the granite areas earmarked as possibles by the South of Scotland Electricity Board who are now test-boring at Banchory.

Brodick Beach and Castle

Of more immediate concern to the Arran folk at the moment is the hot issue of the removal of 6000 tons of sand and gravel annually by Arran Trading Company from Brodick beach. The people of the Rosa Burn are worried because they say it threatens the foundations of their houses. The golfers are worried because they say it threatens the golf course, and geologists believe—or some of them do—that continual extraction in the low water area will cause eventual erosion of the rest of the beach.

Well, who owns the beach? None other than Lady Jean Fforde, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Montrose, who were the last occupants of Brodick Castle before it was taken by the Treasury in lieu of death duties and handed over to The National Trust for Scotland.

And it was from the top floor of the castle I looked down at low tide on the big rent on the beach made since the work began in 1976. To my surprise, I heard that some of the sand goes to Arabia to be used in water filtration.

My own view is that it is not in the interests of Arran, which depends on the tourist trade for its survival, to have any disturbance to one of its great natural assets, the wide sands of Brodick beach. Perhaps the extraction won’t do any harm, and maybe current erosion fears are exaggerated, but set against profits, the possible loss of amenity is too great to risk.

In the castle it was nice to meet my old friends John Forgie and his wife Wilma, who are its joint administrators, which includes its two famous gardens and 7000 acres of mountain. John used to be the art editor of The Scotsman, and Wilma was a freelance artist before they left Edinburgh with their two boys and set up house in the 19th century wing of the old castle which was in direct possession of the Hamilton family for 400 years.

Readers of this magazine may remember his illustrated article, “Home Is A Castle,” in which he described how they have not only to be all things to all people but do all things as well, from book-keeping and accountancy to cleaning drains and cutting sandwiches. In fact, I found them labouring, lowering furniture on a rope from a height to a lower floor.

But life is still full for them, with plenty fun and adventure, and I particularly enjoyed the fine piece of realism in the dungeon, with the hump-back of a prisoner showing under a blanket, and two bare ankles and dirty feet protruding while a brown rat watches. It purports to be “Yellow John,” who was starved before being put to the knife. And on the wall above, scraped with a knife, is an inscription, “May 1715, had barley.”

I also enjoyed seeing the restored old kitchen, which is complete in every detail, with enormous urns, kettles, copper pots, oven for baking bread, and a huge range running the length of the room, a genuine “Downstairs,” only lacking a “Hudson” to make it complete.

The head gardener, who came here 19 years ago when The National Trust took over, is a Leicester man who has grown to love Arran and would never go back. He won 21 awards in the rhododendron show of the horticultural society in 1977. He put his success down to the mild climate, shelter and high rainfall which is just right for him.

In my travels, however, the biggest change I saw in Arran was forestry. I had not realised that the Commission own a quarter of the island and have planted 13,000 acres and have 6000 still to plant. The main trees are Sitka spruce, larch and pine, in that order. The most obvious plantations are in the Brodick to Whiting Bay area, which extends back west round the big waterfall of Glenashdale, reaching up to 1000 feet.

I was surprised to hear that the labour force for all that woodland totals only 14.

The other big change I see in Arran is the number of incomers, many of them craftsmen. The population is rising as news of the good life here spreads. Strange to think, though, that this Hebridean Island is farther south than Berwick-on-Tweed. Sadly, I have to report that Gaelic has died out since I lived in Shiskine in 1939.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here for Tom’s online archives.