Tom Weir | The Hills of Dee

There we were, Adam Watson and myself, watching the sunset gold on the winding Dee from the top of a heathery hill above Glen Dye…

Through a gap in the hills we could see skyscraper blocks in Aberdeen, fairy towers tinged with pink in the soft light, and westward of them the hard blue edge of Bennachie soaring up as if to announce the beginning of the Highlands.

Fields of yellow and green sloped to Banchory and the sweep of the Hill of Fare. Against the red ball of the sun, ridge after ridge stood silhouetted against each other.

“It’s not often you get such clarity in summer,” observed Adam. “From Glas Maol today you could see hills away down the Forth.”

The forecast had been gloomier than the weather turned out to be—only a few showers of hail instead of the snow we had been told to expect on the tops.

We had met up that morning at 9.30 a.m., but had gone our different ways because Adam had scientific work to do with his pointer dogs.

He uses them in his study areas to put up grouse and ptarmigan so that he can count the numbers of adults to young and thus get an accurate picture of breeding success. It is slow, demanding work, calling for concentration, and as tedious for a companion as watching a man angling.

So instead of joining Adam I invited his father to come with me and my wife to Bennachie, which might be old hat to him but would be new to us. I’ve meant to climb it often enough, knowing how beloved it is by Aberdonians.

Strange legends surround the popular summit

Indeed, we were nearly run down by some of the six bus-loads of children aged from six to twelve who were running, leaping and sliding down the path as we got on to the steeps of the Mither Tap.

The 250 or so kids were from various parts of Aberdeen, and it was fortuitous, I learned, that they had all opted for the same outing on the same day. Spread out along half the mountain, they were enjoying themselves on a peak that is just the right height for good fun without too much fatigue.

I was enchanted by the route from Maiden Castle, past the Christian Maiden Stone, a high plinth of pinkish granite embossed with strange Pictish symbols. Weird legends surround the 1000-year-old stone.

Forestry Commission spruces grow above it high on the hill now, which makes the revelation all the greater when you emerge into the open and get the full impact of agricultural quilt of fields and farms rolling in waves below you.

Adam senior swept his hand to indicate the Garioch district extending to Buchan in the east, complemented the other way by the River Don winding to Monymusk:

Ae mile o Don’s worth twa o Dee,

Except it be for fish an tree.

You could see the truth of the couplet in the well-populated countryside with its wealth of farms, compared to the wilder Dee enclosed by hills and woods.

The higher we climbed the more interesting the peak above us looked, a point above a rocky girdle of cliffs with a path winding steeply through them. A portion of enormously thick wall is the remains of an ancient fortification inside which Iron Age men no doubt sought safety.

We chose to scramble up the rocks, stepping on to the summit as a cold shower passed and rainbows stood over the brilliant fields stretching to the sea. Tap o’ Noth, the cone of Ben Rinnes, Lochnagar, the Cairngorms, they were all visible at different times as the showers passed and a superb afternoon developed.

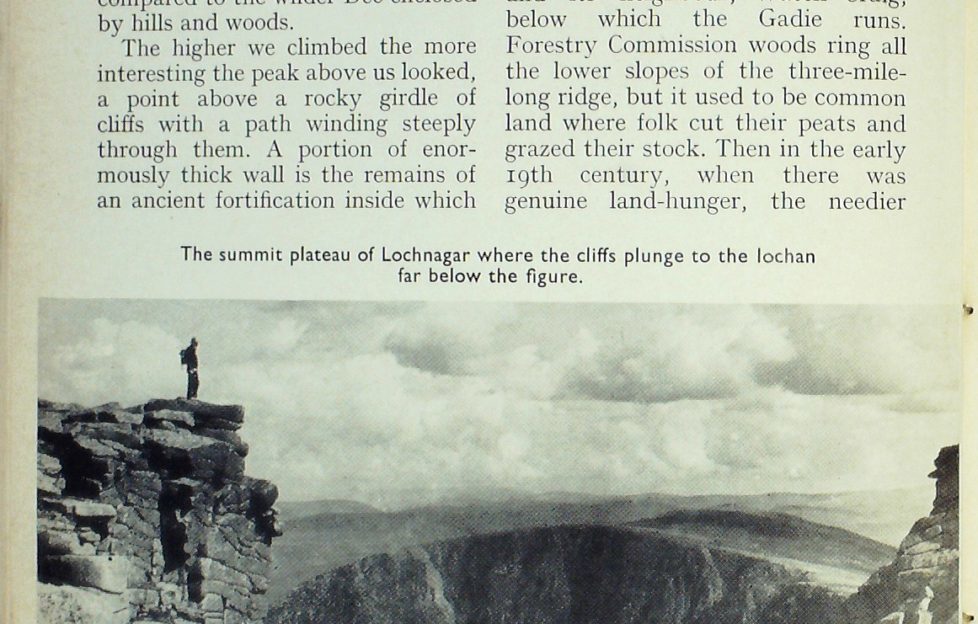

Now we went west to take in the highest “tap,” Oxen Craig, 1733 ft., and its neighbour, Watch Craig, below which the Gadie runs. Forestry Commission woods ring all the lower slopes of the three-mile- long ridge, but it used to be common land where folk cut their peats and grazed their stock.

Then in the early 19th century, when there was genuine land-hunger, the needier folk built shacks on the hill and tried to farm the land. This is when the lairds took action. With the help of Parliament, they divided Bennachie between them, charged rents, and evicted those who could not pa}’. In time even those who stayed had to emigrate, for the land was too poor to support them. Perhaps it was the exiles who sang the song :

Oh, gin I were far Gadie rins

Far Gadie rins, far Gadie rins,

Oh, gin I were far Gadie rins

At the back o Bennachie.

That day, before climbing the hill, we had done a circuit of the Hill of Fare, for I’d just been hearing the words of a new ballad sung to the tune of “Bonny Banchory Oh,” by Scott Skinner. The words, by Mrs Betty Allan, go like this :

It’s uranium they’re after, and they’re bent on howkin’t oot,

And they think we’ve got it here at Bonny Banchory oh!

Weel, we nivver felt the wont o’t, and we’d raither dae withoot,

We’re the guardians o’ this bonny Deeside country oh!

So, we canna lei them connach Bonny Banchory oh!

No, we canna let them connach Bonny Banchory oh!

They wid spoil the Hill o Fare—

Leave it desolate and bare—

No, we canna let them connach Bonny Banchory oh!

The future sad Deesiders, if there’s any livin here

A hundred years fae noo in Bonny Banchory-oh!

Wi their carcinogenic water, and their radioactive air

Will be lookin roon in vain for ony sanctury oh!

Then fit will they think o us in Bonny Banchory oh?

When they’re chokin in the dust at Bonny Banchory oh!

No, we canna let them doon!

We maun aa defend oor toon!

Will the con men talk us roon?

No! Bonny Banchory, NO!

The Hill of Fare is just two miles north of Banchory, a 1400-foot wooded bump surrounded by charming farmland, cut up by tiny roads which are rural backwaters. Local people became alert to the dangers of uranium mining after the Orcadians had rejected totally any prospecting for it, on the grounds that if quantities were found an evil they do not want would be inflicted on them.

Deeside folk are worried because the prospectors, the South of Scotland Electricity Board, aim to prospect in two areas north and south of Banchory. What the local folk would like is a clear statement about what is going on. They want to know what a mine would be like. And they want to know the policy of the planning authorities on uranium extraction.

Since visiting the Hill of Fare, I have been reading a report by Friends of the Earth (Aberdeen) called A Promise to Move Mountains, which is about the search for uranium on Deeside. Other areas where a search may be made to find fuel for future nuclear power stations are Caithness, Sutherland and Skye. Residents in these regions should read this report which is published by Aberdeen People’s Press, 167 King Street, Aberdeen, price 5op.

The dangers are uglier than anything I envisaged, not only because of the mammoth size of the mine-workings, but in terms of radioactive waste or gas which could be released. Uranium is safe in the ground, but when concentrated to produce fuel for nuclear energy it carries grave risks to man and animals. It makes a mockery of any hatching a plan for the next day.

Adam and I talked about some of these things as we sat on top of the hill watching the sunset and hatching a plan for the next day.

A walk through primeval forest

His father would drive us to the Spittal of Muick, leave us there and take the car round to Invercauld, so we would be in position to climb Lochnagar by the north-eastern corrie, traverse the tops and descend northwards through the ancient pines of Ballochbuie, the finest fragment of primeval forest remaining in Scotland.

Nor did that sunset belie its promises for the next day was full of colour, the heather tints nearly as pink as the granite in the Pass of Ballater.

Glen Muick has become more popular since I was last there, thanks to the creation of an information centre for visitors to the Scottish Wildlife Trust Reserve arranged in conjunction with Balmoral Estate.

We didn’t take the path, but struck directly across the north shoulder of the pointed Meikle Pap among blaeberries soon purpling our lips with their juice.

Above us floated St Mark’s flies, little hang-gliders with dangling legs. A grouse rose and pitched down a dozen yards away on top of a heather knoll, her red wattle, speckled throat and reddish breast towards us.

“It’s a hen with young chicks in the heather,” said Adam.

At which the crafty grouse researcher made a sharp staccato whistle in imitation of the anxiety call of chicks. This had an instant effect on the mother. She rose and dropped within a few yards of us. At the same moment three chicks rose, followed a moment or two later by a fourth bird rising to a repeat of Adam’s whistle.

Dr Adam Watson D.Sc., to give him his full title, directs the grouse- research team from the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology H.Q. at Black- hall, Banchory, and much of his work is on the hills and moors studying the behaviour of grouse and ptarmigan.

He told me this had been an unusual year, with grouse on the lower moors doing poorly because of the cold spring and poor heather growth, while the high nesting birds did well because they lay their eggs later and thus missed the killing combination of cold and lack of food at a critical time.

On the other hand, the high-living ptarmigan of the Cairngorms did poorly because so much snow covered their feeding grounds at 3500 feet, while birds on the lower hills did reasonably around 3000 feet. As for dotterel, I was astonished to hear that in late July a cock was still on eggs and that some young were still very small.

“I wish you could have been with us on Ben Macdhui in May; the amount of snow was quite incredible, every bump covered and the sun shining day after day.”

However, you can’t be in two places at once, so I could only marvel at the tales of mid-summer ski-ing while I was out in the Hebrides.

“This is snow-bed vegetation we are on now,” said Adam, pointing to patches of Arctic blaeberry which has bigger leaves and is a darker green than the common plant.

A spot of boulder-hopping

Soon we were boulder-hopping, progressing literally by leaps and bounds on gigantic granite blocks spilling down towards the hidden loch at the foot of the Muckle corrie.

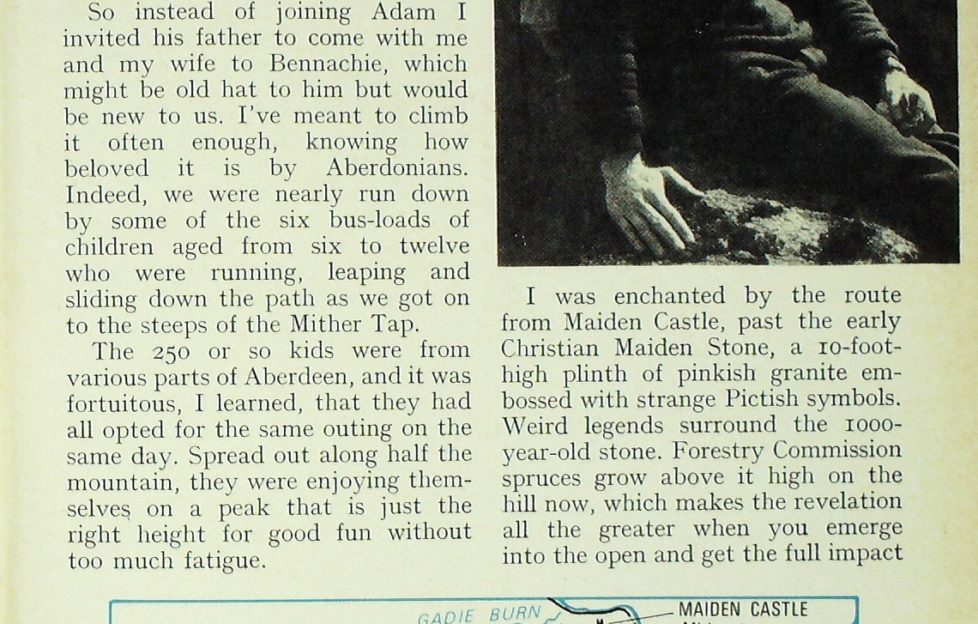

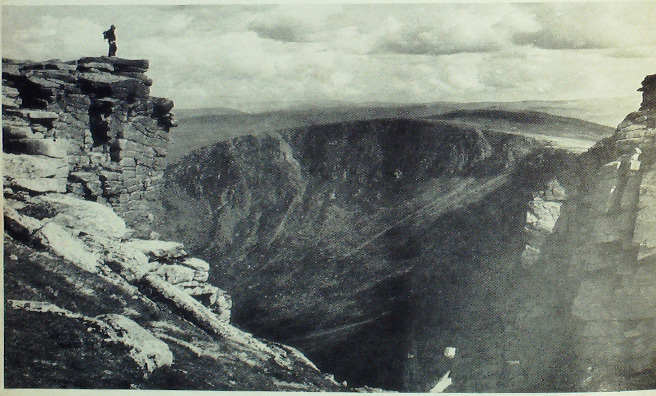

What a spot ! A dark oval of loch beneath a perfect horseshoe of savage cliffs rising dramatically from hanging screes in a total rise of 1200 feet. Halfway up the cliffs, like flies on a wall, were three climbers on Eagle Ridge.

We watched them through the glasses, remembering a November ascent the two of us had done with Tom Patey in grim conditions of rain, sleet and eventually snow.

Today, however, we agreed we would rather be doing what we were doing, enjoying the edge of the horseshoe, scrambling on the boulders in the sunshine and cool breeze. Swifts wheeled over us, and we could hear their wings cleaving the air as they hunted down insects.

” Look! “said Adam as we came over the top. ” There’s Ben Nevis and the Tower Ridge. That’s Morven in Caithness, and there’s your own hills, Ben More and Stobinian, away to the south.”

At the cairn the only sign of the Jubilee bonfire was a black circle on the ground and big granite blocks split with the heat. Snow and bad weather made it dangerous to go up Lochnagar on Jubilee night, and no one knows who put a match to the 10 tons of combustible material which was being kept for mid-summer night.

A perfect late afternoon

Lochnagar is Adam’s favourite mountain, with eleven tops over 3000 feet, 63 square miles over 1250 feet, three corrie lochans, plenty of alpine grassland, shady places where rare alpine plants grow, and, distributed over it from woodlands to summit, the whole range of Cairngorm birds.

We tramped across to the Stuic, past the silky white seed-hairs of the least willow which would soon be blowing on the wind. Deer, rich red in the sunlight of a perfect late afternoon, were lying down or feeding like cattle on the shoulder we were descending. Right in front of us we could see the slabs of Devil’s Point gleaming redly under Cairntoul. Immediately opposite rose Beinn a’ Bhuird and Ben Avon, looking deceptively near.

Now and again we stopped to enjoy the richness of the liglit on the heather and granite boulders at our backs, where last winter’s snow still gleamed. Then we were into the first pines of that most marvellous forest, Ballochbuie, which Queen Victoria saved from the woodman’s axe.

Only a year ago Adam had been in the Cairngorms with Set on Gordon, who died just short of his 91st birthday on March 19, 1977.

It was Seton who introduced Adam to Ballochbuie, Adam had corresponded with him from the age of eight and Seton Gordon had written to him:

It is a fine thing for you to have a love of the hills, because on the hills you find yourself near grand and beautiful things, and as you grow older you will love them more and more.

Prophetic words.

Adam was 13 when Seton took him into Ballochbuie and showed him his first golden eagle eyries.

“His eyes were still alight with enthusiasm as we went over the plateau last year, him in his old patched kilt and deerstalker, talking about the birds, the snow patches, the place-names, just like a young man even if his step was slow and his body a bit bent.”

I had not realised until then that the greatest of the old exploratory naturalists had taken his last Cairngorm walk in his last summer with his most outstanding disciple, for Adam shares all his wide interests while applying modern analytical methods of research which were not in vogue in Gordon’s time.

It was in 1944 that Seton Gordon took Adam to Ballochbuie. In December 1947, in a howling wind, blowing snow and whiteout, I climbed Beinn Mheadhoin above Corrie Etehachan with a red-headed lad from Turriff Academy, who told me his name was Adam Watson.

Even then I knew I would be hearing more of him. Four years later we were in the Arctic together. We’ve had dozens of climbing and ski-ing days on Scottish hills since then, and we will have many more.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday.