The Headless Horseman

Hallowe’en is fast approaching so in the spirit of the season, we’ve dug deep into our archives for the best Scottish ghost stories, and here’s the first one…

I first became aware of the presence of the awesome spectre of the Headless Horseman that haunted the roads of Mull when I was still an impressionable school boy, with two miles of lonely island road to walk each way to and from school, summer and winter.

One morning, I learned that the grocer’s van had been confronted by the spectre at a bend just above our house and had escaped only by cutting the corner and bumping across what was, fortunately, a soft, heathery flat. Why, I saw the evidence of it with my own eyes when I went up and examined the deep tyre marks!

As time went on, more evidence came to my notice. In particular, there were two very ancient trees whose trunks grew almost horizontally along the ground, one by the roadside near Salen (now gone since the construction of the new road), the other beside the bridle path where it skirts Loch Ba, the right of way that once crossed the shoulder of Ben More in central Mull.

The attack of the Headless Horseman

In each case, a Maclean of Duart was walking along in the dusk when he was attacked by the Headless Horseman, who was a Maclaine of Lochbuie and had no use for the Duart Macleans. In each case, the man managed to fend of the ghost attacker with his dirk in one hand, while holding his ground by gripping a young sapling in the other. The struggle went on until cock crow. Then, of course, the spectre had to retire to the Shades, leaving the Maclean men exhausted but safe beside the saplings, which they had almost torn out by the roots during the struggle, and which grew horizontally ever after.

Many a time, as I toddled home in the dark, past the cemetery (which was bad enough!), along the winding road lined by dark, humpy bushes concealing unknown terrors. I quaked at the idea of the Headless Horseman suddenly lowering above me on his black charger, even although I wasn’t a Maclean.

However, when the age of sophistication duly arrived, I wondered if it was more than a coincidence that such manifestations always occurred after closing time! Also, in the newfangled electric lamps on motor cars, the spectre usually turned out to be a wayward sheep or cow, or one of those ponies that grazed freely along the verges of the Glen road.

However, the apparition was good enough to inspire Sit Walter Scott to write the following stanza in his Lady of The Lake:

Sounds, too, had come in mid-night blast

Of charging steed, careering last

Along Ben Talla’s shingly side.

Where mortal horseman ne’er might ride.

Ben Talla, or Talaidh is the 2496 foot mountain whose shapely slopes overlook Glen More, not far from where the story originated.

Now this is where historical lads begin to add some artistic verisimilitude to a sometimes unconvincing narrative.

The Headless Horseman was in fact Eoghan a’Chinn Bhig — Ewen of the Little Head— only son and heir of old John, fifth chief of the MacIaines of Lochbuie, and the event took place in the year 1538.

Ewen’s home lay on the tiny island in Loch Sguabain, in the heart of Glen More. It was a naturally-defensive position with a perimeter wall now barely traceable at the edge of the water, just a few miles through the hill pass from the family castle of Mow at the edge of the sea at Loch Buie.

Ewen was married to a daughter of MacDougall of Lorne, a greedy, ambitious woman. Not satisfied with fine lands in Morvern and parts of Mull generously gifted by Ewen’s father, she nagged Ewen to ask for more and still more, until the old chief decided that enough was enough.

Urged on by his wife, Ewen persisted in his demands, but his father was adamant. Tempers flared and Ewen, torn between his wifes nagging and his filial duties, threatened to take land by force. However, his bluff was called and an armed confrontation could not be avoided between father and son and their respective followers.

In the heyday of the clan system (which was anything but a bad system, if you read it up), such a clan dispute was fought out, rather like duel, in a gentlemanly way, and at an agreed time and place. Ambushes and raids were a part of more generalised fighting.

The glen has more giants, dragons, fairies and tales of the past per mile than any glen I know

I have never been able to trace the exact spot where the fight took place, except that it was a “grassy lawn, where the bones of the dead were interred”, somewhere between Loch Sguabain and Craig, over to the west. Probably it was in the vicinity of the watershed of Glen More at Blar Cheann a’ Chnocain. This is the wildest part of the glen, which has more per mile of giants, dragons, fairies and tales of the past than any glen I know.

The day before the fight, as Ewen was riding along on his “black charger” (probably a stout Highland pony), he espied a tiny woman clad in green, singing a strange song as she busily washed a bundle of blood-stained clothes in a little burn flowing beside the road.

Recognising her as a fairy, and knowing that the Sithichean, or fairy people, could foretell the future, he approached her with due respect, doffed his clogaid and asked if she would be prepared to tell him the outcome of the coming fight.

Without pausing in her work, she gave him the strange reply.

“Beware, Ewen! If butter is placed unasked on your table tomorrow morning, you will prevail. But if it is not, and you have to ask for butter to be brought, it will go ill with you.”

Ewen rode on pondering on the prophecy, his mind uneasy. However, in the excitement of preparing for the fight next morning, he forgot all about it. Sitting down to an early meal, and noticing there was no butter on the table, he had to reprove the serving maid and order her to bring some – and at that point the words of the fairy woman came back to him.

Although filled with foreboding, he marshalled his followers and led them towards the field. Here he found, drawn up in fighting order, not only his father, John of Lochbuie, but his uncle, Maclean of Duart (John’s brother). The wily Duart knew that if Ewen were to be killed, the lands of Lochbuie would be left without an heir, which Duart might turn to his own advantage. This duly came about — but that is another of Mull s romantic stories.

The fight was fiercely contested, but superior numbers began to tell. Seeing his men sorely pressed. Ewen recklessly charged into the thickest of the fight. In so doing, he left himself open to the full swing of a claymore at shoulder level wielded by a Duart clansman, which completely severed Ewen’s head from his body (can we blame his ghost for being prejudiced against Macleans ol Duart?). Anyway, that of course, brought the fight to an end.

Ewen’s last ride

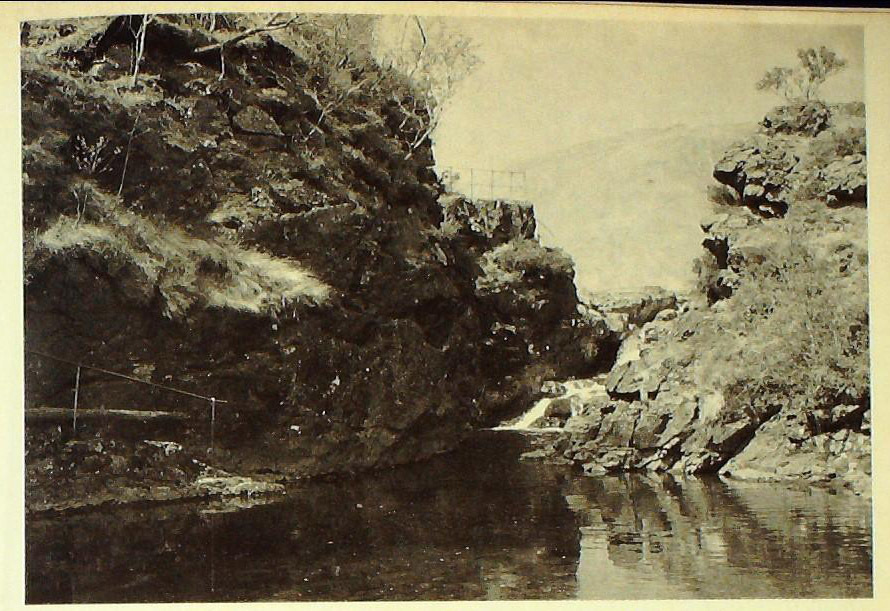

With the headless body jammed in its stirrups, Ewen’s maddened horse bolted from the scene of carnage eastwards along the course of the River Lussa for two miles or more, to the right-angled bend below Ben Talaidh, where road and glen now turn sharply to the south. The tiring horse splashed across the ford above the Falls of Lussa and came to an exhausted halt at the top of the sleep slope above—just below the present new road and the ruins of the homestead of Torness.

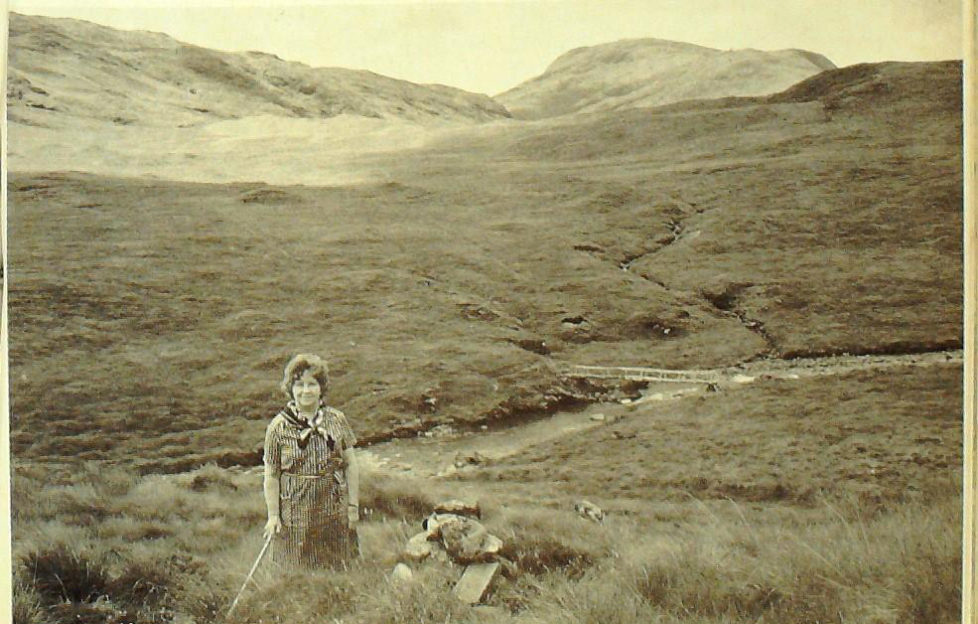

Here, the headless corpse slipped out of the stirrups and fell to the ground. Ewen’s followers set up a tiny cairn to mark the spot, and the body was interred temporarily a short distance away. It is said that when Ewen’s favourite hunting hound set eyes on his master’s body, every hair fell off his body!

Now I had often heard rumours about the existence of the cairn, the location of which was lost and forgotten as the stones sank deeply into the heather. However, during exchanges of correspondence in the 1960s I asked the late Seton Gordon if the story about the cairn was true, and if he had any idea where it was. To my delight, he replied (I have his letter before me) that he had, in the past, received exact directions from one of Mull’s most authoritative historians, Robert McMorran of Treshnish, who had died earlier in the century.

I was advised to look for the “small cairn, moss-grown and deep in the heather, little more than a hundred yards below the ruined cottage at Torness (the only building on the west side of the road), higher up the river and a little above the Falls of Lussa.”

Seton Gordon was sure that in that year, 1968, the only people left who knew the location and the full story were Mr Mclnnes, the hirer from Fionnphort, and himself.

Soon afterwards, when going to fish the Lussa with my family, and accompanied by Mr David Guthrie James, of Torosay Estate, we had little difficulty in finding the lost cairn, exactly as described. It lies beside the path where the descent begins to the footbridge over the river, a short distance above the Falls. I keep adding a stone or two every time I pass and now it is quite easy to locate.

Not only did the ghost of Eoghan a’Chinn Bhig haunt the roads of Mull, but it has even been known to become airborne and visit the island of Coll, another ancient land of the Macleans (how he must have disliked them!).

Again, his steed used to be heard galloping furiously round the old keep of Moy when death or misfortune was about to afflict the house of Maclaine. The keep has long been unoccupied and is now ruinous, and the lands of Lochbuie are in the hands of strangers.

It is doubtful if the Headless Horseman finds it worthwhile now to leave the Shades and haunt the busy Mull roads. The nights would be too short to do justice to his hauntings and, anyway, the police car would soon be there to sort out the facts!

Check back next Monday for another ghost story from our archives.

- The Falls of Lussa, where Ewen’s horse crossed the river carrying his decapitated body.

- By the long-lost cairn that marks the spot where Ewen’s body was temporarily interred.

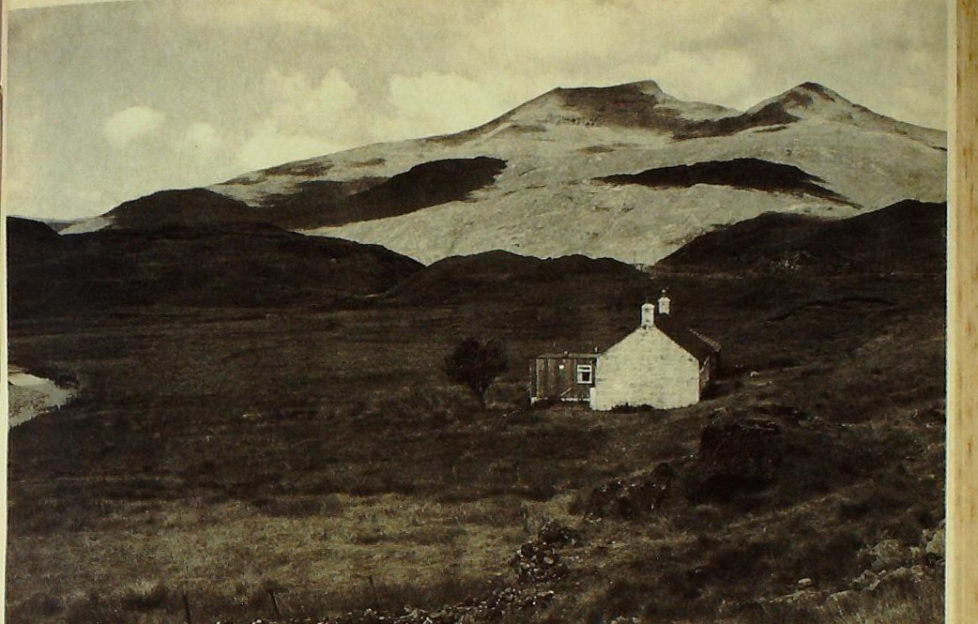

- The writer believes this cottage overlooks the battlesite where Ewen was killed.