Tom Weir | The Land of Knapdale

Knapdale holds some incredible and ancient secrets – for those who know where to look…

The trouble about driving to North Knapdale in brilliant weather is that before you can break into that complicated country of narrow lochs and headlands you have to pass through so many places where you’ll want to stop.

My wife certainly couldn’t pass through cheery Inveraray when there was a display of arts and crafts in the kirk. And I could not turn away from Loch Fyne without calling at Ardrishaig to find out how the dry summer was doing with that most rural of waterways, the Crinan Canal.

“No bother,” smiled Brian Adam who takes the cash and hands out lock-operating instructions to yachtsmen. Apart from the sea-lochs and swing bridges at top and bottom of the 9-mile canal, passengers do their own locking, sharing them with other craft where possible in order to conserve water, since it costs 65,000 gallons to make each opening.

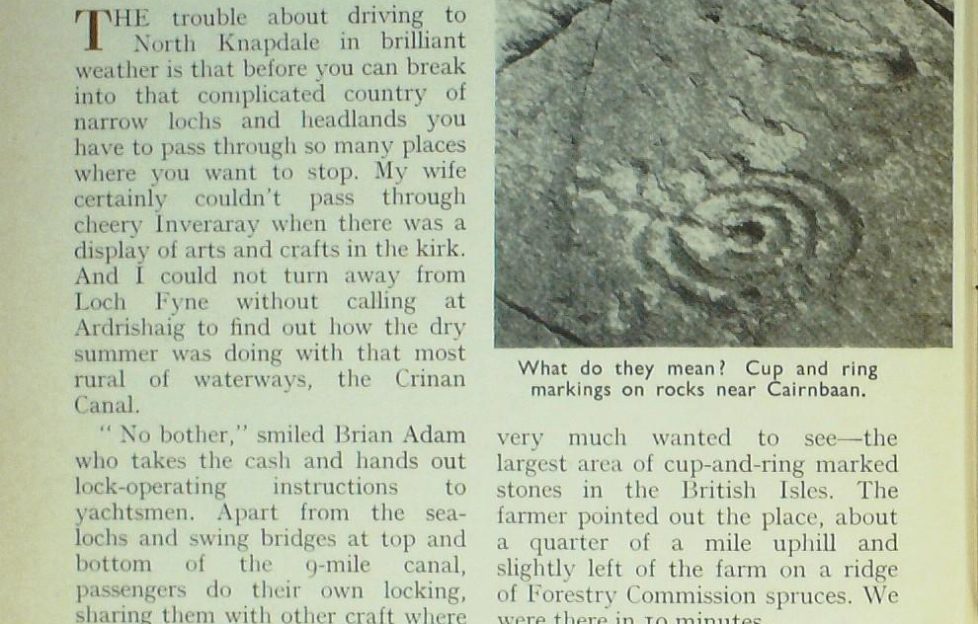

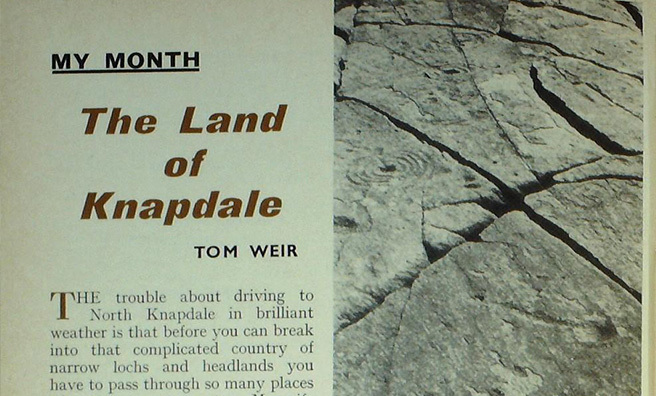

Following the canal north, I turned east off the road a mile short of Cairnbaan at a sign to Achnabreck Farm, for there was something I very much wanted to see—the largest area of cup-and-ring marked stones in the British Isles. The farmer pointed out the place, about a quarter of a mile uphill and slightly left of the farm on a ridge of Forestry Commission spruces. We were there in 10 minutes.

A Prehistoric Puzzle

I have seen a few of the 300 listed cup-and-ring marked sites in Scotland, but nothing to equal the scribblings and indentations on these brown and grey slabs of inclined schist. Professor Alexander Thorn of Oxford University has posed the question:

“Do they contain a message, or are they the beginning of a form of writing?”

Here on this natural gallery of rock under my feet the artists of the past had really gone to work, inscribing not only concentric circles of various sizes, but overlapping them, dotting some with deep cups for centres, or scooping out whole .series of cups. And from some of the circles vertical incisions were off-set like exclamation marks.

For over a hundred years petroglyphs of this cup-and-ring variety have been a puzzle, since they are not confined to Scotland but have a near world-wide distribution according to Ronald W. B. Morris, who, in the past 13 years, has made them his special study and whose recent book, The Prehistoric Rock Art of Argyll, led me to this site.

Mercifully, the Forestry Commission did not surround this first of three collections with trees, so I could look out from the carvings on a sweep of Loch Fyne. Open views are characteristic where cup-and-ring markings occur, says Morris, and usually there is a view of the sea or estuary. Also, they are usually within six miles of places where copper or gold has been worked. There was certainly plenty of copper around Kilmartin just round the corner, where I would have loitered to look at some of my favourite ancient monuments had it not been for the necessity of pressing off west if we were to reach Tayvallich before mid-evening.

“Everything conspired to make the moment of arrival a magic one”

I love the drive up from Cairnbaan following the canal and looking north over the strange sea-level flat of the Moine Mhor under rocky Dunadd, where the history of Scotland as a nation began with that Antrim tribe who made it their kingdom. And what a change of scene when you swing on to the B8025 at Bellanoch through a trench of dense conifers, continuing all the way along the narrow salt-water slit of Caol Scotnish!

Suddenly all is change again as from out of the conifers you swing into Loch a’ Bhealaich and find yourself looking down on islets white with the wings of hovering terns, and across a horseshoe bay bright with the sails of boats, with the neat houses of Tayvallich ranged round an amphitheatre of rocky hills.

Everything conspired to make the moment of arrival a magic one: the richness of the early evening sunshine on the boats and the rocks and the water; the movement of three yachts curving in gracefully from the main artery of Loch Sween through the tern islets of this loveliest of the five heads of the long sea loch; the cool breeze which we were feeling for the first time that exceptionally hot day.

Tayvallich is derived from the Gaelic, tigh – house, and bealach -pass, and it’s a perfect description, for in less than a mile through the hills you come to the Sound of Jura and the curve of a perfect bay called Carsaig. This was the place to camp, and there was plenty of room amidst spacious greenery with no more than the odd caravan or two on private sites. Nor were there more than 20 people on the beach.

Fine to get the tent down near the farm, cook a meal and eat it while watching the sun sink towards Jura, then set off through natural oaks to the ridge-top to watch the red ball make a path of crimson on the placid sea where eider ducks floated and terns fished. I enjoyed some good rock scrambling, too, before turning in at what passed for darkness on a cloudless night.

“We had the world and the narrow road to ourselves”

The heat of the sun woke us, and I had a stroll to enjoy the singing of the redpolls and sedge warblers flighting over the burial ground of the Campbells, where twites added a Hebridean touch to the scene. Tayvallich was hardly awake as we crossed the pass and turned right, continuing on the B8025 down the Linne Mhuirich, which could be called the thumb of Loch Sween, lying as it does at an angle to its other probing fingers.

Apart from a distant figure turning hay with a fork, we had the world and the narrow road to ourselves, and I was thinking of the once busy traffic of agile cattle that flowed up this way a hundred years ago, walking themselves to Crieff and Falkirk by way of Tayvallich, Kilmichael Glassary, then by Loch Awe and Loch Fyne.

The drovers had loaded the cattle at Lagg in Jura, sailing them six miles across to land them at the end of our road, at Keills, where I was looking forward to seeing the old jetties. It came up to expectations, especially the north landing, built with long slabs of grey stone laid in such a way that you could climb by a rough staircase from the water to its now collapsing top. But the south jetty was intact and angled to allow the cattle to scramble up by an inclined ramp.

The boats were wherries of wide beam lined with heather on which the cattle stood, their heads secured to rings on the gunwales. Road engineer John Mitchell, who got a lift in one of these boats, left us an account of his passage in his Reminiscences :

At hist we cleared the land. How the wind did roar, and how the cattle struggled to get their heads free. The extent of sail we carried was forcing the bow of the boat too deep into the sea, and there was fear of being swamped.

But the beasts could smell the grass, and as they neared Keills they were thrown overboard and swam the last bit to the jetty to scramble ashore. I found it easy to envisage the scene, and hear the shouts of the drovers and the barking of dogs as the cattle were formed for the march which might take nine or ten days.

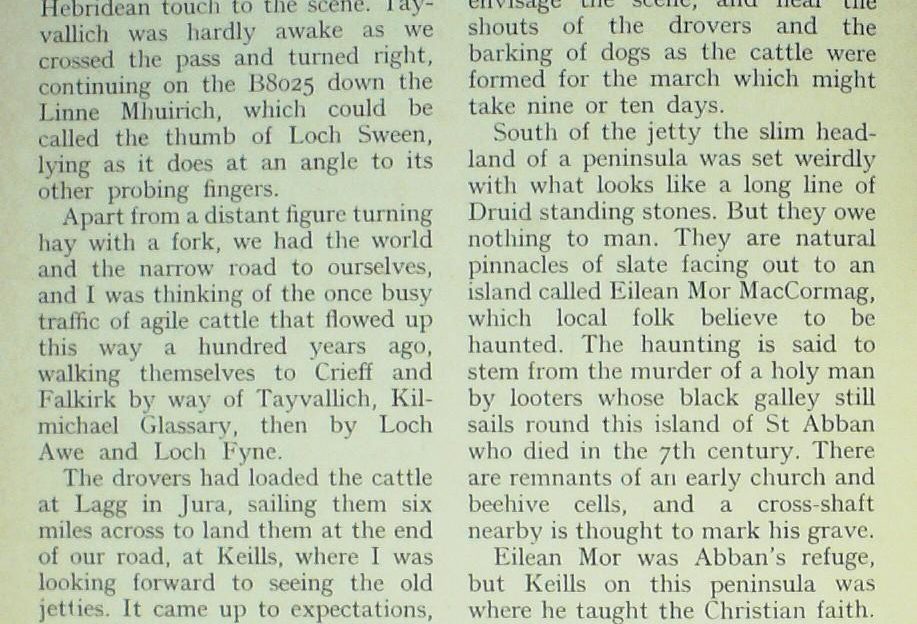

South of the jetty the slim headland of a peninsula was set weirdly with what looks like a long line of Druid standing stones. But they owe nothing to man. They are natural pinnacles of slate facing out to an island called Eilean Mor MacCormag, which local folk believe to be haunted. The haunting is said to stem from the murder of a holy man by looters whose black galley still sails round this island of St Abban who died in the 7th century. There are remnants of an early church and beehive cells, and a cross-shaft nearby is thought to mark his grave.

Eilean Mor was Abban’s refuge, but Keills on this peninsula was where he taught the Christian faith. All that remains to show its former importance is a medieval chapel used as a museum for worn carved stones, and above it a 9th century Celtic cross. The Solway pirate Paul Jones is said to have been hereabouts in 1779, no doubt waging war on British vessels and taking prizes between Eilean Mor and Ireland.

Of forestry and seed oysters…

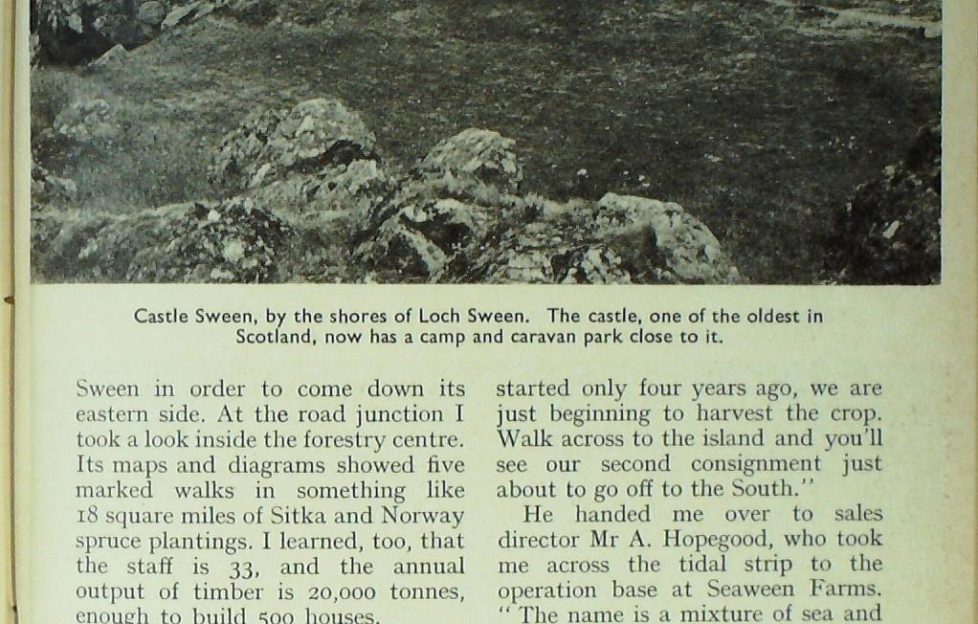

To explore further it was necessary to go back to Tayvallich and drive northward through the Knapdale Forest to turn the five heads of Loch Sween in order to come down its eastern side. At the road junction I took a look inside the forestry centre. Its maps and diagrams showed five marked walks in something like 18 square miles of Sitka and Norway spruce plantings. I learned, too, that the staff is 33, and the annual output of timber is 20,000 tonnes, enough to build 500 houses.

We had not gone very far before I met one of the buyers of local timber, Mr L. Moir, who was bending over some green painted wooden trays on the shore. I went over for a chat.

“I’m laying down seed oysters. We rear them, and we have about quarter of a million coming to maturity in this bit of water. We hope to raise the figure to ten million if the starfish will let us. An oyster takes about three seasons to complete its growth, and as we started only four years ago, we are just beginning to harvest the crop. Walk across to the island and you’ll see our second consignment just about to go off to the South.”

He handed me over to sales director Mr A. Hopegood, who took me across the tidal strip to the operation base at Seaween Farms.

“The name is a mixture of sea and sween after the loch. This is the product.”

In a box in front of me was an unappetising-looking mess of warty brown objects. Mr Hopegood took one up, put in the point of a penknife, prised it open and inside were two leaves of pearly flesh.

“Like to try it?” he invited, pouring off the surplus moisture. I shook my head, at which he swallowed with an appreciative look on his bespectacled face. “Lovely, but too expensive! The price at Billingsgate is £220 per 1000. I’d like to see it come down for oysters deserve to be more popular. But it’s the law of supply and demand. I’ll take this lot to Colchester where they will sell for 20 pence apiece on the stalls. In 1962-63 the Portuguese oyster was wiped out in the Colchester area. These are Japanese oysters, equal if not superior to the native oyster. We buy the seed from a farm near Connel, and the great advantage of rearing them here is the purity of the water. Experts who know oysters say they have never tasted better. Loch Sween is dead right for us because of its great length, and the way the temperature builds up in a narrow head like this. It makes it rich in phyto-plankton.

“But it’s a high risk game because of the time the oysters take to grow, and all the time they are subject to predation by starfish which we are learning to control. We have to, or they would clean us out. Both of us were planters in the Far East before turning to oysters. We were in the oil palm industry, so we are accustomed to overcoming natural problems by trial and error.

“We do everything ourselves, with the help of one employee. We buy in the wood, make the trays, put in the seed oysters, cover them with nylon netting, and sink them in racks 15-20 feet below water. We inspect each tray five times a year by hauling them up, using a boom on a raft. The fresh seed you see there will be harvested two to three years from now.”

I left him packing his oysters in bags topped with seaweed, ready to motor South, deliver the goods and do a bit of commercial travelling to open up new outlets. Present productivity is 1000 a week, and the oysters will keep from seven to ten days out of water.

Twisting down the narrow road, we swung west at a sign pointing to Castle Sween. There was no sign of it until we turned a corner, and then there it was rising squarely behind a large camp and caravan site above a bay alive with what looked like sailing dinghies gone mad. In the keen breeze the coloured craft would shoot forward at high speed, then go about in a swift turn and come racing back with a manoeuvrability I had never seen before.

In fact, they were not boats but surfing boards with a keel and a sail, balanced by bodies in wet-suits who seemed to be able to make the craft do anything. I went down to find out about it and found that the sport had been introduced here for the first time this year, and that for £7.50 you could get a five-hour course of instruction or hire a wind-surfer for £4 for four hours.

One of the instructors described the technique. “It’s mainly balance, though you do need a certain amount of strength in your fingers to manipulate the sail-bar.”

I left him and made my way over to Castle Sween, the oldest castle in the West. I had not expected anything so impressive considering it was built between 1125 and 1135 by Somerled to help drive the Norsemen from Kintyre and Knapdale. Sween is derived from Suidhean, meaning warrior. The Vikings were defeated, and that success led to 300 years of rule by the kings and lords of Somerled’s Clan Donald, whose base was Islay. Perched grandly on a sea cliff with a floor space of 70 feet by 50 feet inside, the enormously thick-walled tower of Castle Sween was added to in the 13th century. It looks impregnable, but Robert the Bruce captured it twice in the 14th century and Alasdair MacDonald, fighting for Montrose against the Covenanters and the Campbells, burned and destroyed it in 1644.

I was sorry to find the inside of the castle being used for a football game by youngsters who could just as easily have played outside, which shows what comes when planners allow a camp and caravan park on both sides of a historic castle. Surely the bay used by surfers and dinghies would have sufficed without encroaching northward.

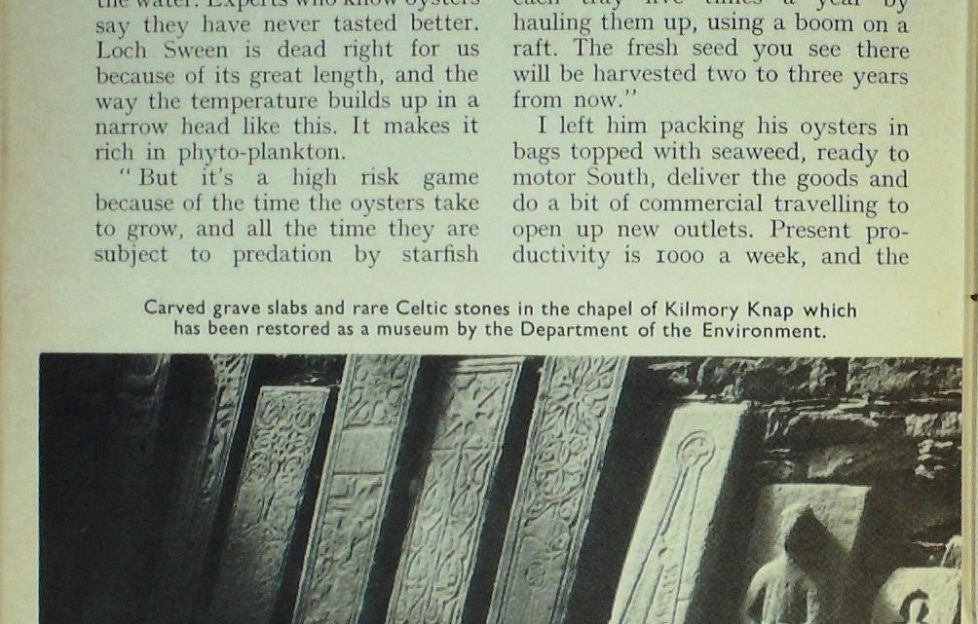

Back on the main road we drove to its end at Baliinore, stopping en route to look at the 13th century chapel of Kilmory Knap, another of the sites of this name which honours St Maelrubha of Applecross. Restored as a museum, you open the thick oaken door with a huge iron key and find inside a collection of carved grave slabs and rare Celtic stones. In contrast, however, to the fine work done by the Department of the Environment, the junk lying about the steadings beside the chapel is a disgrace. The splendid MacMillan’s Cross is a 15th century work of art, but it looks down on 20th century ugliness.

From the chapel a track runs down to the sands of Kilmory Bay, a blissful spot where we paddled our feet and later on as the evening cooled, watched another perfect sunset from the top of a hill. Now I could identify the silver slits of sea dividing the parallel headlands containing Loch Sween, while by contrast the eastern ridges inland shone pale white with quartzite.

What a strange country, with all the linear features flowing north-east to south-west, the hard grits protruding from the grey schist like ribs. The very word Knapdale is derived from the Norse Knapper- dal, meaning knobbly dale, a perfect description of its pointed hillocks.

Check back here every Friday for more from Tom Weir

More from Tom

For more of Tom Weir’s fascinating columns click here.