Tom Weir | A Cliff-top Walk, The Helicopter Threat and A Village with a Past

In the spring of 1977 Tom Weir was mesmerised by the changing seasons, and was determined to do his bit to preserve the natural, unspoiled beauty of his country…

Every ice age had its interstadials, periods when the earth, warmd up, vegetation grew, and animals returned to the land.

As I write this it is snowing, yet a week ago the skylark was silvering the sky with song, and five buzzards were having a game of tag over the oak wood where in the past I have found an eyrie.

Trim mergansers were neck jerking to their dowdy mates that morning while golden eye were busily backheeling water over their backs in time to clownish head movements. Teal were yelping and wigeon by the hundred whistling. Spring, it seemed, had arrived after a week of keen frost, heavy snow and severe floods.

I love the atmosphere of South-western Scotland

It certainly felt that way when I set off with my wife, bound for Galloway. The warmth of the sun through the car windows, and the velvet sheen on the rolling Ayrshire down lands lulled one into forgetfulness of the black ice still lurking in shadowy places after a night of clear sky.

It was great to see the dark hump of Ailsa Craig and the peaks of Arran softly gleaming with new snow.

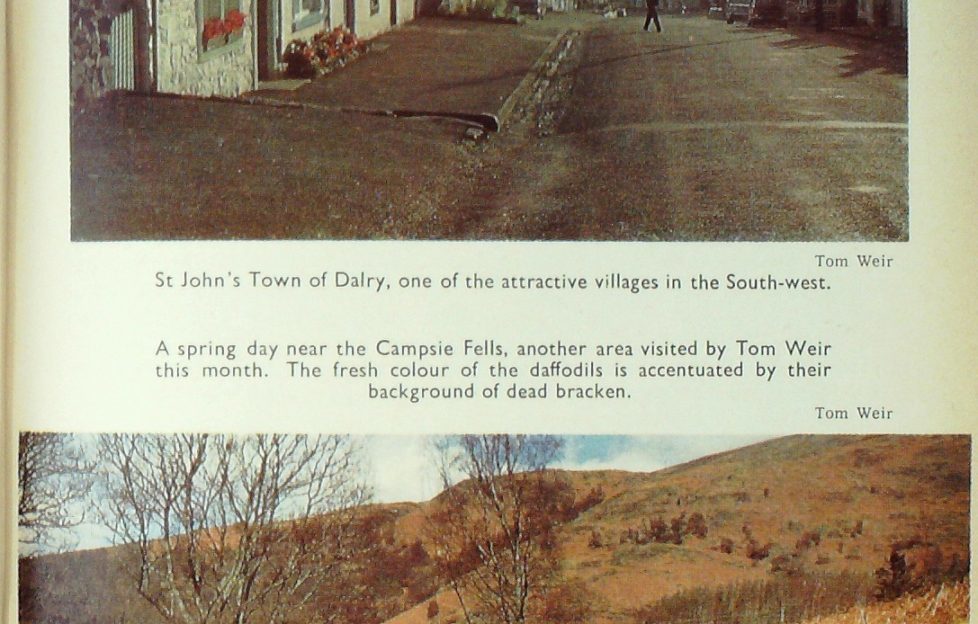

I love the atmosphere of South-western Scotland with its attractive villages – St John’s Town of Dairy, New Galloway, Gatehouse of Fleet and the rest – and I could have stopped often there was so much to see.

But there was no time to stand and stare at the forest tide of dark green breaking over the foothills of high Galloway, for I was due on the platform at 3.30 p.m. to give a talk at the Annual Week-end Conference of Young Farmers’ Clubs, whose theme was “Beyond Our Ken”. My job was to present a panoramic view of Scotland to about 300 lads and lassies gathered together from the Clyde area to the Solway.

They were a responsive and cheery crowd, and it would have been grand to stay with them at Gatehouse and join them for dinner and a dance, but we had accepted an invitation from my old climbing pal, Professor Sir Robert Grieve, to spend the night in his new home at Cairnryan, so off we went.

The beginning of that 40-mile drive was memorable for the splendour of Wigtown Bay, dyed crimson in the fire of the west where the sun had set.

Voyages old and new

The ebony black peninsula blocking the bay was Rurrowhead, near whose tip a Briton by the name of Ninian set up the first Christian church in Scotland in the fourth century, Candida Casa, the white house.

Over there, too, above the gravelly shore, is the cave which was the special retreat of this very first Scottish saint.

The pleasurable part of the drive west ended at Newton Stewart when I was faced with the uncomfortable surprise of one heavy vehicle after another in a constant stream blinding me with their lights. It was traffic from Ireland. I had not realised that Cairnryan is now the main port of entry to Scotland and that a steady shuttle service of ships serves the port night and day.

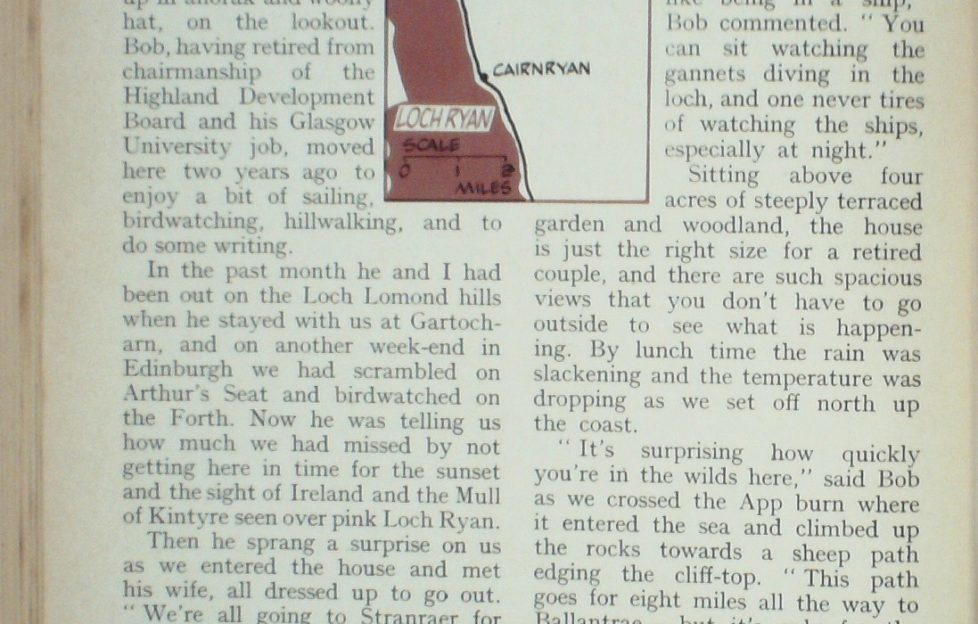

My instructions were to head north up the Girvan road towards Glen App. And soon there was Bob, happed up in anorak and woolly hat, on the lookout.

Bob, having retired from chairmanship of the Highland Development Board and his Glasgow University job, moved here two years ago to enjoy a bit of sailing, bird watching, hillwalking, and to do some writing.

In the past month he and I had been out on the Loch Lomond lulls when he stayed with us at Gartocharn, and on another week-end in Edinburgh we had scrambled on Arthur’s Seat and birdwatched on the Forth. Now he was telling us how much we had missed by not getting here in time for the sunset and the light of Ireland and the Mull of Kintyre seen over pink Loch Ryan.

Then he sprang a surprise on us as we entered the house and met his wife, all dressed up to go out. “We’re all going to Stranraer for dinner with daughter Elizabeth and her husband. They’re looking forward to seeing you. Let’s go.”

Well, that was a great night, a fine meal, and grand company which included Robin Grieve (no relation to Sir Robert). He is a local doctor who as a student used to be in the popular BBC radio programme Down at the Mains. He played the part of Tam Scott, Farmer Scott’s son.

I learned a lot about the South west that night, aye and in the morning, too, for it was 3 a.m. before I got to bed. So there was no stirring until after nine, and very little point either, for the rain was battering the window of the high, perched house whose garden ends in a virtual cliff.

“It’s like being in a ship,” Hob commented. “You can sit watching the gannets diving in the loch, and one never tires of watching the ships, especially at night.”

Sitting above four acres of steeply terraced garden and woodland, the house is just the right size for a retired couple, and there are such spacious views that you don’t have to go outside to see what is happening.

A Cliff-top Walk

By lunch time the rain was slackening and the temperature was dropping as we set off north up the coast.

“It’s surprising how quickly you’re in the wilds here,” said Bob as we crossed the App burn where it entered the sea and climbed up the rocks towards a sheep path edging the cliff-top.

“This path goes for eight miles all the way to Ballantrae — but it’s only for the sure-footed. Wild goats use it, and it goes right along the edge of some big drops. We’ll follow it for a bit, then strike over the tops and drop down into Glen App. It will give you a good idea of the variety of country in a short distance.”

Uncertainly did, as we looked down precipitous cliffs from which rose flocks of rock doves, while above us mountain hares, still in white, scurried over the heather. On one side we had eiders and cormorants and screaming herring gulls, and on the other meadow pipits and redwings. Leaving the sea to climb over the top we passed stone-covered green mounds, forts or burial cairns of ancient man dating long before St Ninian.

Then down into the shelter of Glen App and its woods.

“We could have done the whole walk, Ballantrae and back, if the weather had been reasonable,” said Bob. “We’ll do it next time and see everything there is to see. The views are terrific on a clear day – you can grasp the geography of the Firth of Clyde in a glance. And there’s a lot to explore in the Rhinns, too. The cliffs at the Mull of Galloway are great for birds and for rock- climbing!”

That’s the joy of being an outdoor man. Life can never grow stale. Bob loves the Highlands as much as he does Galloway and he could be happy in either place, but he and May like to be near his daughter and grandchildren, so he has opted for here.

He still has a busy public life for he serves on various committees including the Mountaineering Council for Scotland of which he is chairman.

The Helicopter Threat

I knew the Council had been objecting to a proposed helicopter service from Aviemore for joy rides into the Cairngorms, and I told Bob I had been glad to know they fought against the proposal. I had written a personal letter to the Highland Regional Council before they approved the application hoping it would help have the application rejected.

Other bodies who objected were the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Association, the Strathspey Conservation Group, the Countryside Commission for Scotland and the Nature Conservancy Council whose job it is to manage an area of out-standing scenic and wildlife importance. A well-attended meeting of local people voted with a two-thirds majority against the proposal.

The Regional Council chose to ignore these objections and give the all-clear to Travel Centre (Norwich), Ltd. And they did so only a day or so after mountain rescuers brought down a pilot and film cameraman suffering from exposure after their helicopter had been forced down on Loch Avon.

Television film a few days later showed a larger helicopter retrieving the first one in a difficult operation.

Approval of this application is all the more retrograde when you consider that the reason why the summit bothies were removed from the Cairngorms was because they were a temptation to climbers who might go up there depending upon them, and perhaps freeze to death like the six members of an Edinburgh school party who failed to find the Curran bothy.

It is my view that anyone who goes into the heart of the Cairngorms should pay the capital price of foot poundage, which is harder currency than sterling. Consider that skiers with cash could be dumped on the top of Braeriach or Ben Macdhui in a few minutes flying time, irrespective of their ability to cope with the biggest plateau in Scotland. This service could send the accident rate shooting up.

The operators say their helicopters would be available for mountain rescue if required. I would demand that the operating company be made to pay for all searches and rescues occurring as a result of their dropping clients in the wilderness area of the Cairngorms. Unfortunately, it is the ratepayers who have to foot the bill and mountain rescue teams who do all the hard work.

But that is only one side of the story. What about summer-time when thousands of campers and caravanners are enjoying the Glen more Forest Park? They go for the peace of the place, not to endure the noise of helicopters making three and four-minute circuits from 10.30 to 12.30, and from 13.30 to 15.30 five days out of seven. The service is not only against the interests of the majority of Cairngorm lovers, but to my knowledge no one is asking for the service other than the operators.

There is a point of principle at stake. Loneliness and silence are important ingredients in the magic of the Cairngorm plateau and its huge corries where snowfields rarely melt. This is the only fragment of the Arctic in Britain, in its plant and bird associations, with glens of ancient pines where merlin, golden eagle and greenshank are free from disturbance because of remoteness.

Conservation depends upon the balance of accessibility and in-accessibility. Landowners in the Cairngorms have already breached this principle by driving roads over the high tops for deer-stalking. Chair-lifts and ski-tows have brought the northern corries within easy reach of the multitude. I deplore the first, while welcoming the second. It is good that anyone is enabled to enjoy a part of the Cairngorm experience without physical toil which may be beyond them.

But something is lost for ever if the wild is taken out of wilderness. The erosion of the Cairngorms has gone far enough. We have to be firm about these helicopters because the time is coming when a new generation of tracked vehicles will arise, capable of travelling anywhere on snow or on heather. The principle of absolute conservation must be upheld or areas of outstanding landscape value like the Cairngorms could be seriously degraded. Vehicles of any sort should be barred.

The Secretary of State for Scotland is bound to have the final say before the helicopter service can start operating, even for the trial year which has been proposed. He should be left in no doubt as to the strength of feeling. He must be influenced by the fact that the area is protected by a National Park Direction Order, and that the wilderness between the Spey and the Dee is amongst the best wild-life regions in the whole of Europe.

A Village with a Past

When the melting snow was sending a fine flood down the burns, I went out to Campsie Glen for a scramble up Jacob’s Ladder to see again the variety of waterfalls and spouts that made this one of the best-loved places in Scotland, when Campsie had a railway station served by the Kirkintilloch and Aberfoyle lines. For working-class excursionists of my mother’s generation, this was the closest Highland scenery to Glasgow.

That day I made it my business to find out something about the Clachan of Campsie at its foot. A native of the place not only put me in the picture but took me to a large, rectangular depression beside the burnside.

“That was a pit which could be filled with water from the burn, and it was used to ferment the tlax when this was a weaving village of about 20 houses. Wee as the Clachan is, it had the parish church for the whole neighbourhood.

“Take a look in the churchyard,” he said. “The tradition is that St Clachan settled at Campsie in the 9th century, and founded a kirk which became the parish church for the neighbourhood until it was replaced by one at Lennox town in 1829. So all we have here now is an ivy-covered ruin and a belfry surrounded by ancient tombstones, including one of a murdered minister, the Rev. John Collins, who was waylaid by the Laird of Balglass so that he could take over the parson’s beautiful wife.

“Did you know that Crichton’s Cairn, that high top above Campsie Glen, takes its name from another 17th century minister of the parish? He is immortalised from the fact that he could go from the Clachan to the top in 20 minutes–good going for 1200 feet of climbing. It seems he did it to compose his sermons, maybe to get away from the noise of weavers’ shuttles. The cairn was built to his memory.”

It was grand to meet such a well- informed man. As I came down to the old road, intending to walk it to Lennoxtown, I saw I was being watched by another man who advised me against it.

“The right of way was closed years ago, and you’ll be turned back,” he warned me. And having said so, he launched into the story of Lennoxtown.

“It was forecast that grass would grow in the streets of Campsie one day. Look at the work there used to be here calico printing and bleaching. It started in 1786 and went on for 150 years, then the whole trade went to England. We suffered here in the 5os 1 can tell you.”

Those were the days when I first knew Lennoxtown, and then its dereliction was too much like Glasgow for my taste. I saw it as the eyesore of the Campsies. Today I see it differently, for it’s a little town with a line setting. Its main source of employment is Lennox Hospital, within the policies of Lennox Castle, the former home of the Kincaid Lennox family, whose connections go back to the 10th century. The hospital provides about 600 jobs, with another 400 in the railworks and pulp container firm.

On the way home I visited, for old times’ sake, the former Campsie Glen Railway Station, now a dwelling-house, and behind it I took the grassy track that used to carry the line. It skirts the hospital grounds and follows the “Crooked Strath” past Fin Glen and the Spout of Ballagan to emerge in Strathblane in the country of volcanic necks.

For people in the Glasgow area this wee trip round the Campsies makes a grand and not very strenuous outing, using the bus to Campsie Glen, and returning from Strathblane. Services are good in both directions. If you would like a view stretching from Ailsa Craig and the Loch Lomond hills to Ben More and Stobinian and Ben Vorlich, let me recommend Drumgoyne, easily reached from the Blanefield War Memorial. Just walk up the pipe track, or take in Slackdlru on the way.