Tom Weir | Murray’s Way

TOM WEIR went to Lochgoilhead in the spring of 1977 to talk to the mountaineering legend W. H. MURRAY about his life of climbing and writing

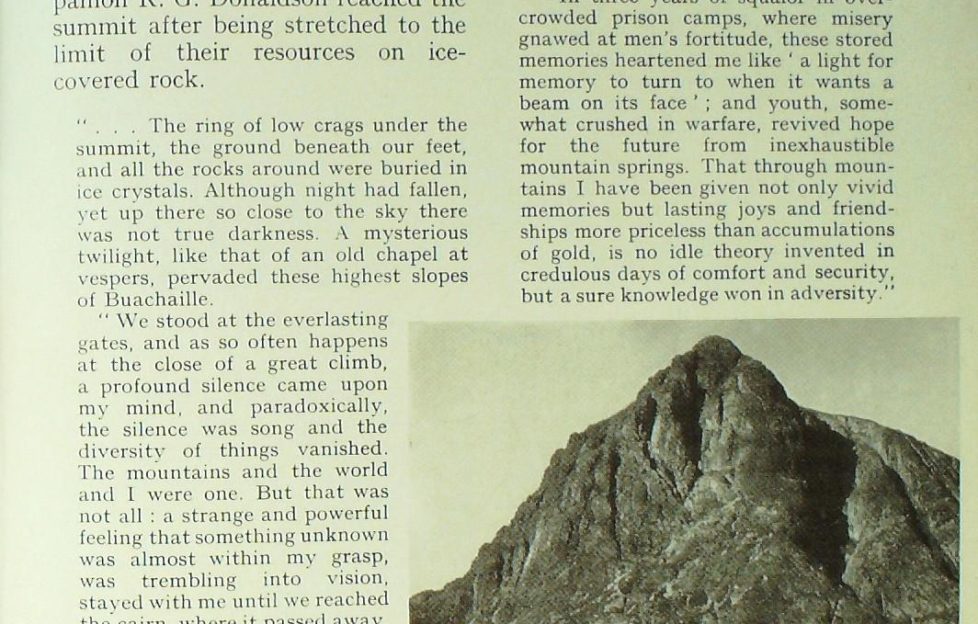

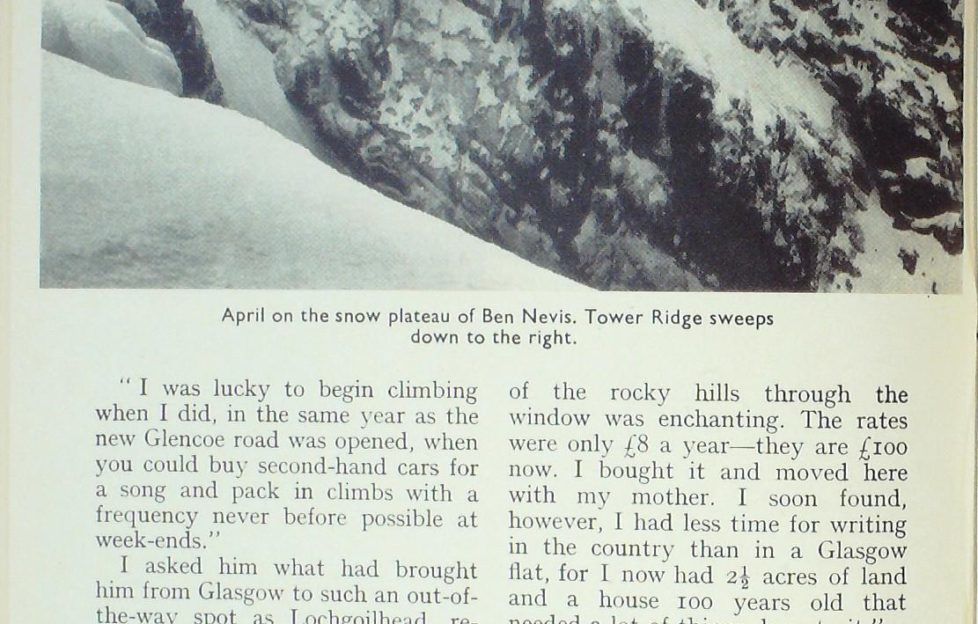

“… in the worst days of the war there shone most often before my eyes the clear vision of that evening on Nevis, when the snow plateau sparkled red at sunset, and of Glencoe, when the frozen towers of Bidian burned in the moon. In the last resort, it is the beauty of the mountain world in the inmost recesses that holds us spellbound, slaves until life ends.”

The inmost recesses, those of the soul … In the whole corpus of Scottish mountain literature only one mountaineer could have expressed these sentiments so delicately.

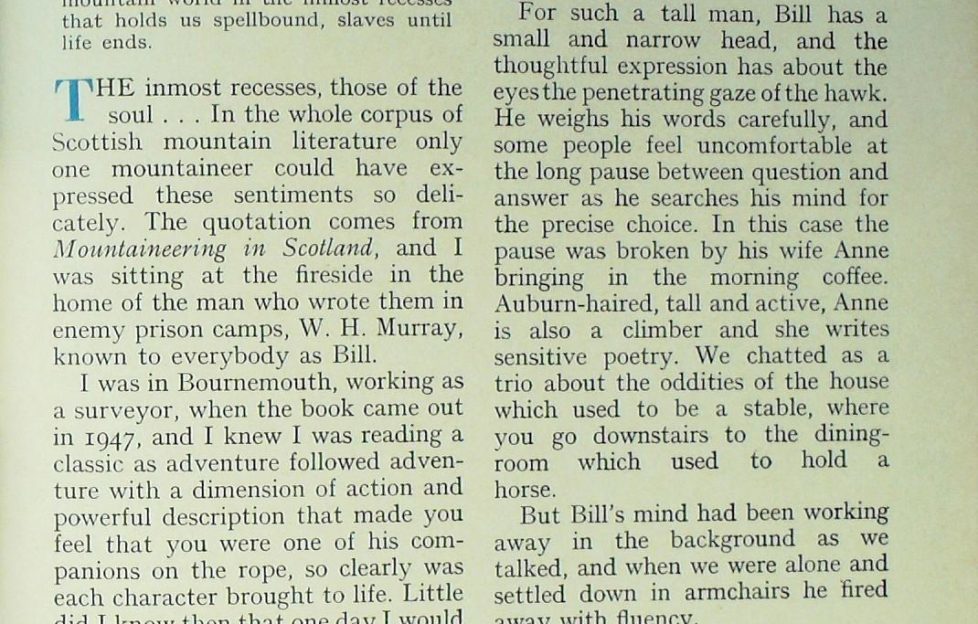

The quotation comes from Mountaineering in Scotland, and I was sitting at the fireside in the home of the man who wrote them in enemy prison camps, W. H. Murray, known to everybody as Bill.

I was in Bournemouth, working as a surveyor, when the book came out in 1947, and I knew I was reading a classic as adventure followed adventure with a dimension of action and powerful description that made you feel that you were one of his companions on the rope, so clearly was each character brought to life.

Little did I know then that one day I would be off to the Himalaya with three of the men mentioned in the book, one of them Bill Murray himself.

Down the years we have retained contact, but this was the first time I had visited him at his home perched on the rocky shore of Loch Goil.

Since that first book Bill has written 19 more and won many honours. I suggested to him that it was time he wrote his autobiography since he has so much to say that nobody has heard yet, but the humorous glint in his blue eyes showed me he didn’t take me seriously.

“Tell me the background to your present life, for I’ve never really known despite the times we’ve had together.”

For such a tall man, Bill has a small and narrow head, and the thoughtful expression has about the eyes the penetrating gaze of the hawk.

He weighs his words carefully, and some people feel uncomfortable at the long pause between question and answer as he searches his mind for the precise choice. In this case the pause was broken by his wife Anne bringing in the morning coffee.

Auburn-haired, tall and active, Anne is also a climber and she writes sensitive poetry. We chatted as a trio about the oddities of the house which used to be a stable, where you go downstairs to the dining- room which used to hold a horse.

But Bill’s mind had been working away in the background as we talked, and when we were alone and settled down in armchairs he fired away with fluency.

The desire to be a mountaineer

“Until I was 19, mountains never entered ray consciousness. Not until I overheard two men talking about a mountain called An Teallach. They were describing a thin, narrow ridge above the clouds with shafts of sunlight striking distant seas and islands. To me it was a positive revelation— a vision of a strange new world, here in Scotland, and not abroad.

“So one April day I went to the Cobbler. I wore my ordinary clothes, shoes, collar and tie. I went to the Cobbler because it was the only mountain I knew by name. There was hard, frozen snow in the corrie, and I kicked steps in it naturally since without an ice-axe it was the only way up. I was frightened by the consequences of a slip, but I got to the top of the centre peak. The rocks of the south peak were bare of snow, so I scrambled up. From the tops I saw a seascape of snowy mountains for the first time. The desire to be a mountaineer was born at that instant, but the idea that any one person could climb them all didn’t seem possible.

“I joined the Scottish Youth Hostels Association. In these days of the mid-thirties there were innumerable small hostels, and for a year I climbed by myself, in the Trossachs, the Crianlarich hills, the Cairngorms and on Liathach in Glen Torridon. It was from people in the hostels that I first heard about mountain clubs, and as I wanted to be a rock-climber I joined the Junior Mountaineering Club of Scotland in 1935.”

Bill was a trainee banker at this time, which was interesting enough to him, but he spent a lot of time writing short stories, mainly about people in ordinary human situations.

“Even at school I wanted to be a writer, but such a career seemed impossible for a boy, because you need experience of life to be a writer.”

He was to gain it in the next four years with the men who took him to the Crowberry Ridge and shocked him with its exposure, but exhilarated his mind with the totality of the experience.

“I would say I was a naturally good mover on rock and soon came to enjoy the exposure, but what really drew me to winter climbing on the great routes was the nervous tension and suspense which kept building up until you reached the top. Then the relaxation and exhilaration.”

A mysterious twilight, like that of an old chapel at vespers…

Listen to this, after climbing the Crowberry Gully in January 1941 before going off to join the Middle East forces in Egypt. It was Bill’s 80th ascent of the Buachaille Etive Mor, and at 7.15 he and his companion R. G. Donaldson reached the summit after being stretched to the limit of their resources on ice-covered rock.

” . . . The ring of low crags under the summit, the ground beneath our feet, and all the rocks around were buried in ice crystals. Although night had fallen, yet up there so close to the sky there was not true darkness. A mysterious twilight, like that of an old chapel at vespers, pervaded these highest slopes of Buachaille.

“We stood at the everlasting gates, and as so often happens at the close of a great climb, a profound silence came upon my mind, and paradoxically, the silence was song and the diversity of things vanished. The mountains and the world and I were one. But that was not all : a strange and powerful feeling that something unknown was almost within my grasp, was trembling into vision, stayed with me until we reached the cairn, where it passed away.

“We went down to Glen Etive for the last time, and I fear we went sadly. The moon shone litfullv through ragged brown clouds.”

Bill has no doubt at all in his mind that these pre-war years on the Scottish hills were his best, and that nothing that has come to him since in the Alps or on Everest has brought the ecstasy of climbing hard routes with well-tried companions when he was physically fittest and enthusiasm was highest.

For him the men and the mountains came together at the right time. This is what he wrote in reflection as a prisoner of war.

“In three years of squalor in overcrowded prison camps, where misery gnawed at men’s fortitude, these stored memories heartened me like ‘ a light for memory to turn to when it wants a beam on its face ‘ ; and youth, somewhat crushed in warfare, revived hope for the future from inexhaustible mountain springs. That through mountains I have been given not only vivid memories but lasting joys and friendships more priceless than accumulations of gold, is no idle theory invented in credulous days of comfort and security, but a sure knowledge won in adversity.

” I was lucky to begin climbing when I did, in the same year as the new Glencoe road was opened, when you could buy second-hand cars for a song and pack in climbs with a frequency never before possible at week-ends.”

To live among growing and living things

I asked him what had brought him from Glasgow to such an out-of- the-way spot as Lochgoilhead, remembering the icy and twisting single-track I had descended from the summit of the Rest-and-be-Thankful by Glen Mor.

“After being demobbed, and having given up the bank to try to earn a living as a writer, I was determined to find an environment among growing and living things. I came to see this house on an April day when the cherry blossom was out and the sea loch Mediterranean blue. The view of the rocky hills through the window was enchanting. The rates were only £8 a year—they are £100 now. I bought it and moved here with my mother. I soon found, however, I had less time for writing in the country than in a Glasgow Hat, for I now had 2 and a half acres of land and a house 100 years old that needed a lot of things done to it.”

Lochgoilhead was a place to work, nor was its isolation irksome, for he was more often away than in it during the exploration years in Garhwal, in North-west Nepal, and on the Everest reconnaissance with Shipton, finding the route up the Western Cwm by which the mountain was successfully climbed in 1953. Since 1969 he has led four trekking trips to Nepal, taking people to 18,000 feet, so he can hardly be said to be a stay-at-home even now.

He believes that it is important for a writer to get about. While a working writer certainly has the advantage over others of being relatively unaware of high rainfall and restricted, views, he nevertheless requires the stimulus of change if he is to keep writing.

What of writing as a way of life after 20 books since 1947?

“I’d never advise anyone to take it up as a career. You can earn a lot more with very much less mental stress if you work for an employer. Personally, I never worried until inflation started, but full-time writing is no longer economically viable by itself. You have to keep your mind in a money-earning groove, so one cannot write what one likes. To me the most enjoyable form of writing is fiction, using one’s creative imagination, but unless you hit the jackpot the return from it in Britain doesn’t justify it. You must have American sales. Of my six thrillers, two were not worth writing from the financial aspect.

“The chief pleasure for me of being a writer is the sharing of experience with a wider public, of events from which I have derived great enjoyment. A non-fiction book takes me two years to write, and I find the hardest aspect the planning of it. Once you have got this out of the way it’s the library work that takes the time. The county library service is very good, but you have to spend days in Glasgow and Edinburgh filling loose-leaf notebooks with notes.

“For books like The Islands of Western Scotland, The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland, The Hebrides, and my most recent one, The Scottish Highlands I get advice from experts on what to read about their subject, be it geology, archaeology or whatever. Then when I have written the stuff I send it to them for vetting.

“Looking back, I have no regrets. I think I have had a good life doing what I have done since I have no talent for any other occupation. Medicine is something I might have gone in for …”

He left that statement unfinished, and I remembered how in the Himalaya he had devoted a lot of time to doctoring the sick who came to our camps. His two best-selling books to date are The Story of Everest, published in the year of the first ascent—a tale of the mountain from its first sighting to its eventual conquest. It sold 30,000 copies, and went into eight foreign translations. His Companion Guide is running second now at over 20,000 and still selling.

On the outstanding beauty of the Highland scene…

One of the more abstract jobs he undertook was to make a survey of the North for the National Trust for Scotland, resulting in a book called Highland Landscape, identifying the regions of supreme landscape value. It meant walking over the ground and assessing it against his personal experience of the territories over a period of 30 years.

In his conclusion he writes :

“The outstanding beauty of the Highland scene, which is one of the nation’s great natural assets, has been haphazardly expended and no account kept. The wasting away of this asset is bound to continue and to accelerate unless discrimination and control arc brought to bear by some body created for the purpose and granted powers by the Government, so that checks and safeguards may be instituted. If action to that good end be not taken now, the Scottish people will lose by neglect what remains of their natural heritage.”

Well, a body was formed, the Countryside Commission, and Bill Murray has been a member of it for 10 years. Alas, however, it is not an organisation of real power. Its work is mainly inspirational, and in the end it is the local authorities which call the tune. But Bill has made his voice heard, which is the reason why he is Chairman of the Scottish Countryside Activities Council, representing 30 organisations and 400,000 countryside users.

Until recently, he was Chairman of the Mountaineering Council for Scotland, which is the voice of all mountaineers to Government, and to all others having responsibility for mountain land. It works in partnership with the British Mountaineering Council of which Bill was vice-president. In addition to that he was President of the Scottish Mountain-eering Club from 1962-64.

“I had to give up some of these posts because I wasn’t getting enough time for writing or climbing. They’ve been very good for me. I’ve learned a lot and know the value of the work that has to be done if right decisions affecting the Scottish countryside are to be made. There are whole areas of Argyll where no conservation principles are being put into effect, and that includes Lochgoilhead.”

Buchaille Etive Mor remains his most loved mountain. He also has, in his garden, a steep face of rock which even by the easiest way gives a severe problem that a few good climbers have failed to solve. Bill can still do it,

“Because I know the holds,” he confesses. Nowadays he seeks out more moderate climbs when he goes to the Buachaille, and winter ascents are by the easier gullies cutting steps in the old way. Not for him the modern style.

“If I were starting again I would be all for the special tools and techniques which enable you to climb steep ice as if you were on rock.

“To do it you need a lot of practice. But I have my reservations. Hamish Maclnnes says it has taken a lot of fun out of winter climbing. My own view is that earlier climbers probably got a bigger kick with nothing more than nailed boots and axes than the modern generation get with advanced aids. And when you think of it, the pioneers who did the classic winter climbs on Nevis, Glencoe and other places published astonishingly little detail about the routes. They minimised the difficulties which must have been considerable.”

On mountains the need for constant vigilance on steep places is the hardest lesson to remember, and the one which even the best climbers forget at the cost of their lives. The danger is part of the fun. It breeds self-reliance, though Bill is sure the mountains cannot be used for character-building, for something goes astray the moment you try to organise.

Bill Murray is extremely glad that he started off alone, finding his own way. ” I am sure I would have lost half my enthusiasm if I had been led by a qualified instructor.” He joined a club when he was ready for it, and there met the team-mates who formed the strongest climbing partnership of the ’30’s. He regards the clubs as being “Mountaineering’s essential backbone—a framework on which tradition and development naturally hang and grow.”

Bill’s full title is Dr W. H. Murray, O.B.E., and he is the holder of the Mungo Park Medal of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

For his book, The Story of Everest, he received the United States of America Educational Award. His topographical books are amongst the best that have been written in Scotland. Amongst his novels, I rate Five Frontiers the highest.