Tom Weir | Days I Won’t Forget

Winter arrived in a gale of blattering rain from the south, dying out overnight and transforming the roads to ribbons of black ice by morning.

Fog lay over the land, but I suspected I would climb into sunshine on Duncryne and the moment was magical when, at 350ft, I saw blue sky above me. Suddenly I was in a silvery world of ridges and peaks standing above rolling seas of cloud. Yes, and I had Brocken spectres, too, not brilliant ones, but transitory haloes of rainbow forming round my shadow on wisps of mist rising from below.

Two magical hours on the hill

I would have abandoned writing that day and taken to the Luss hills on my skis, but alas I had to go to Glasgow, to be fitted out with a morning suit and top hat for meeting the Queen at Buckingham Palace. Still I had a magical two hours on the hill, enjoying the windless air and the sight of the houses, trees and fields emerging.

On my walk that day I was putting up wisps of snipe from the unfrozen places, and, surprisingly, flushed a partridge – a bit of a rarity in these parts.

Just before the old-fashioned winter set in I had enjoyed a wonderful December walk along a drystane dyke separating field from forestry plantation. There is a mighty beech tree here whose overhanging base gives a sporting ascent on wrinkled holds, and I was just about to take off my jacket and climb it when out of the whins nearby I caught a movement. Then I glimpsed the whiskery face of a cat.

One of those lucky days

I froze against the tree as a striped body emerged, and I paid attention to the “ring” tail and the fact that the cat was heavy with kittens. The “tread” of the animal was more tigerish than the domestic tortoise-shell, but it was when she paused and half-lay on her side as if resting the kittens inside her that I was able to take stock of the large face, black stripes and strongly marked tail-rings of grey and black.

Distance from me was about 50 yards, and it was when she rose and made for the dyke with purposeful tread that you saw how like she was to a tiger. She disappeared, leaving me puzzled. If this cat was 100 per cent wild, why should she be carrying kittens in December when May is the normal time for kittens? My friend David Stephen suspects that when we know more about wild cats we shall discover that, like the otter, it will breed in any month of the year.

Moving on, I was brought up short by sounds within the forest – quarrelling swearwords which I couldn’t place but suspected might possibly be from jays. Yet they seemed to be coming from low down on the ground, and in ten minutes the harsh fracas was getting closer. Then into view came the acrobatic shapes of darting grey squirrels, glimpsed as they pursued each other through the lower branches of spruce trees. For me it was a new sound, despite the fact that I see these animals nearly every day. Indeed, they have been exceptionally common in recent months, so that I wonder if these are neurotic sounds arising through their becoming a nuisance to one another. It is exactly 100 years since the grey squirrel was introduced into Britain, and they have now completely vanquished the red squirrel from Dunbartonshire.

I had hardly moved on before I saw a roebuck heading my way across the field. Through the binoculars it made a fine sight, little antlers held high, mouth open and tongue visible as it sailed through the air between leaps. It was making for the dyke and I was preparing to watch it make the big spring over, when it shied away, trotting up and down the dyke looking for a place to jump, turned about and headed straight for where I was standing. It got within yards of me before it got my scent, whirled round, charged for the dyke and in a marvellous five-foot-high leap sailed over, leaving me with a vision of shiny black nose, white breast spot, and absolute litheness of small brown body.

These three events happened within the space of half an hour, yet many a time I have walked there and seen nothing out of the ordinary. It was just one of those lucky days.

Nature at work

There was another unusual happening as I sat at work at my desk recently. A shape shot past the window, and next moment from below the level of my feet I could hear the distress calls of a bird. Gently opening the window, I craned my neck forward and looked down on the spread wings and barred tail of a sparrowhawk, its fierce yellow eye turned to stare up at me. It must have relaxed its grip on its prey, for next moment a blackbird shot out of its clutches and flew low along the wall of the house. The sparrowhawk rose at an angle and in a lightning loop fastened on the blackbird again and bore it down to my compost heap.

I let it enjoy its catch in peace since I am no enemy of the way nature works, but I did think it was cheek when it returned a day or two later and perched above my window so that I could see its projecting tail without rising from my typewriter.

Stone of the Britons

That month I had the notion one sunny morning to oblige a reader and go seeking a stone called Clach nam Breatann in Glen Falloch. I had visited it once before, a long time ago, and I remembered it was hard to find for it is not on the map. Clach nam Breatann is Gaelic for “Stone of the Britons”, and it is of significance because it marked the northern boundary of Strathclyde, beyond which was Pictland.

I made the mistake of parking at the Falls of Falloch, when it is better to drive a mile on up the glen, park at a good layby on the west side and begin the climb by passing under the West Highland Railway by a cattle creep. You do not see the stone until vou have climbed a few hundred feet to a skyline beyond which it is conspicuous, perched on a pointed knoll. A local name for it is the “Mortar Stone” because from the south it looks like a piece of artillery.

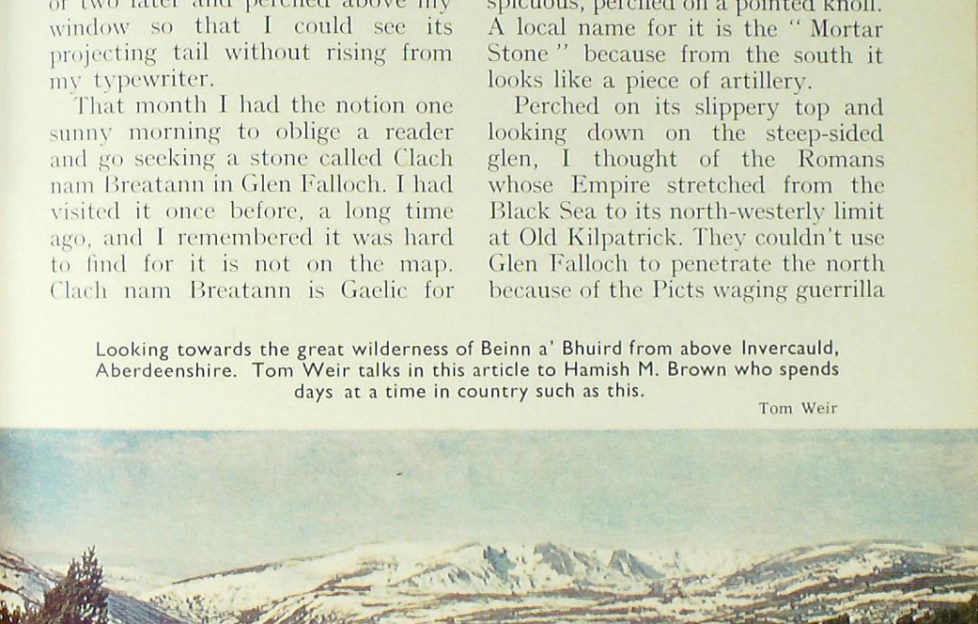

Perched on its slippery top and looking down on the steep-sided glen, I thought of the Romans whose Empire stretched from the Black Sea to its north-westerly limit at Old Kilpatrick. They couldn’t use Glen Falloch to penetrate the north because of the Picts waging guerrilla war from these slopes. And even in the expansionist times when the Romans left and the power of Strathclyde grew, they could not contain the native Picts and the Scots from Antrim who combined in 843 to form Alban under Kenneth McAlpin.

Clach nam Breatann leaps into history when Robert the Bruce, in 1306, after his defeat by the English at Methven, headed west and was unlucky enough to fall in with the McDougalls below Ben Lui in Strath Fillan. Bruce was routed in that battle and forced to turn south. In Glen Falloch he paused with his 500 men at Clach nam Breatann before pushing down the eastern side of Loch Lomond to Inversnaid. The stirring events that broke English domination of Scotland were yet to come.

From the Stone you can drop to the railway in a north-easterly direction and find, in less than a mile, a path which takes a short-cut to Crianlarich. It is the soggy remains of General Caulfield’s military road, and it speaks of other conquests, the pacification of the Highland clans, the introduction of sheep and the exploitation of the Caledonian Forest. I walked along the path whose northern signpost was the snowy top of Ben More against which remnant Scots pines of the most southerly fragment of ancient woodland stood bravely.

The route to ourselves

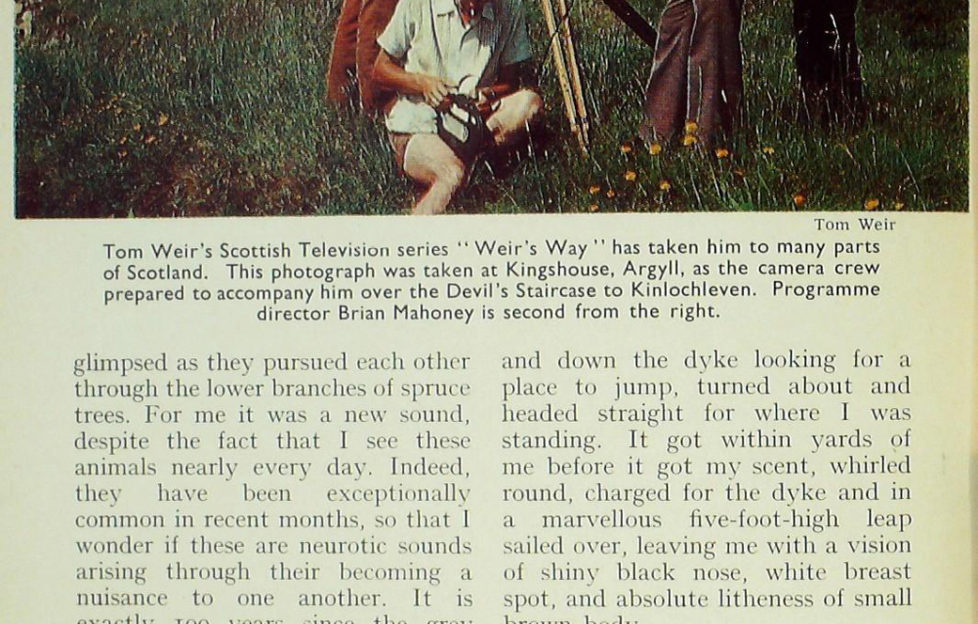

During the summer I had followed Caulfield’s road right across Strathfillan and over Rannoch Moor, then across the Devil’s Staircase to Kinlochleven. This was for a new series of my television programme, Weir’s Way, and some of that journey made in a heatwave, with hordes of clegs and midges, had been memorable enough.

What surprised the camera team was to find that we had the route to ourselves. We met no walkers except in the Glen Nevis gorge, yet the roads were humming with traffic. One of the things I find interesting, working with different production teams, is how they grow to like the hills. Indeed, cameraman Harry Bridges has become a Munro-bagger on his own account and now claims a score of 20.

Perhaps some of this was due to a programme I did with Hamish Brown in the Arrochar hills with Hamish recounting his great trip across the Munros in a single walk of 1640 miles in 112 days and 450,000 feet of climbing. I was impressed at the lightness of his rucksack containing nylon tent, sleeping bag, stove, pots and food. I could lift it easily with one hand and reckon it was hardly more than 20lb.

Hamish grudges time spent in motor cars, and believes that to get the best out of the hills you should expedition across them, using bothies, or camping, carrying your own food and bivvy material. He can afford to look for novelty, since he has now done all the Munros five times. A few days before I wrote this he knocked on my door at 9am to talk about the sharp peaks of the Garhwal Himalaya where he plans to go next year as a member of a lightweight expedition to bag Himalayan Munros of around 20,000 feet.

Despite wintry weather, he was just back from a high camping trip in the Braemar copies of the Cairngorms, and as we talked he told me something of his background which was new to me. Born in Colombo in 1934, one of his earliest memories is of his parents going off to climb Fujiyama, leaving him disconsolate. But they did take him to the Valley of a Thousand Hills in Natal. A banker in Japan, Hamish’s father had to make an exciting escape from Singapore to reunite with the family in South Africa before coming back to Scotland. With such outdoor-loving parents, Hamish began on the right footing, though it was in the Ochils while at Dollar Academy that he learnt his stuff.

He grinned when I asked him what he had done in the way of work since his R.A.F. days as a National Serviceman. “Lots of things. I’m a ‘stickit’ minister – I was for two years an assistant in a Paisley parish. I gave it up to teach English at Braehead, Buckhaven, then went on to outdoor activities. I was there for twelve years, and readers of The Scots Magazine will probably remember some of the articles I wrote of our doings.

“Now I’m a freelance mountaineer/instructor, writer and lecturer. I do mountain guiding by arrangement. I organise regular holiday courses in winter and summer. I just like being amongst the hills, and I have probably an unrivalled knowledge of the Highlands and Islands off the beaten track. I have almost finished a book on the long walk across the Munros. I’ve written fiction stories for magazines, and a guidebook to the Isle of Rum. I’m very happy – and very poor.”

But rich in experience through his travels in Ethiopia, Cyprus, Morocco, the Andes, Pyrenees, Corsica, Poland and most alpine regions of Europe. From among a lot of adventurous men I know, I cannot think of another who has crammed so much into a mere 43 years. The basic thing is, of course, that he is prepared to barter security for mountains, and has the capacity to enjoy a full life NOW, rather than playing safe and laying up treasures for his old age. Being a bachelor helps, of course.

Buckingham Palace Honour

Back from Buckingham Palace, and to the strains of For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow, sung by the village school children, I had to tell them everything that had happened, from going through the portal to the inner court to coming out and doing the television interview which they had all seen on the box. It was a big night for Gartocharn, since my neighbour Jim McKechnie was on the same Scotland Today programme, having won five of the top awards at Smithfield, including the Supreme Championship with his year-old steer, Fizz. No single man has ever achieved such a record in the history of Smithfield, yet Jim rears cattle only as a hobby; he gets his living from selling fruit.

Jim could tell them about Princess Anne handing over the coveted trophy at Smithfield. Now that they were into the world of Royalty on a personal scale, they were agog to hear what the inside of the Palace was like, so I told them about the gorgeously carpeted art gallery of pictures into which we were ushered to await being called to the Throne Room. The time had been 10.30am, and there would be about 200 of us assembled when our attention was called in a friendly manner and we were instructed what to do.

“It’s all very easy,” we were told. “What it boils down to is just doing what the man or woman in front of you does. And enjoy it!” Time sped as our ranks thinned, and within an hour I was formed up with about 20 of the “S’s” and “W’s” and marched along a corridor to enter the fairyland of the huge, high and decorated ceiling of the Throne Room.

The senses could hardly take it in – a stage with a ray of crimson velvet suspended from a ceiling-high golden crown, and below it the Queen, lit in a shower of diamond light sparkling from two crystal chandeliers. Then the eye took in the two thrones and the rich uniforms of the Yeomen of the Guard with their steel halbards – medieval figures in a setting of marble pillars and sculptures and frescoes.

I was moving across the room as I took it in, enjoying the music of the strings playing a tango as I followed the kilted figure of Andy Stewart, neat and jaunty and showing no signs of weariness despite having travelled overnight following two performances of his Ayr show.

A tap on the shoulder and now it was my turn to walk over to the Oueen, make my bow, and step up to the dais to have the M.B.E. pinned on my lapel. As she did so, she asked me about my work and where I did it, holding out her hand for me to shake as she straightened up. As I took my three backward steps to bow departure, I had the chance to see how simply she was dressed in a silk frock of quiet floral pattern with a brooch at the neck and pearls.

On the opposite side of the room I was ushered to a chair among the assembled guests among whom were my wife and sister who had a grandstand view of the whole affair and loved every minute of it, from the bestowing of Knighthoods to the final medals for gallantry awarded to soldiers, policemen and others. Then came the National Anthem, and the departure of the Queen with her Yeomen, and we filed out.

On the stairway were the same statuesque figures we had seen on the way in, Gentlemen-at-Arms in knee-high leather boots, shining breastplates, plumed helmets and swords, holding themselves so stiffly erect and unmoving that they could have been dummies. I asked Andy Stewart how he had enjoyed it all. “Very much. For stage-management, it was an eye-opener. You couldn’t better it. What style and efficiency!”

For us the show wasn’t over. Andy was doing a piece on the Palace steps for the B.B.C. before flying back North for two shows in Ayr that night. I was doing one for Scottish Television, and in the interview I was asked why I thought I had been honoured with the medal. I told them it certainly would have dumbfounded my mother, who could never understand the life I had chosen. She used to tell people, “He can be away for months, and when he comes back he just sits there – write, write, writing. Jings, he should get a medal for it!”

“Well,” I told them, “here’s the medal, and I hope she’s looking down from up yonder on her two weans at Buckingham Palace today!”

Afterwards we headed north out of London for Pinner, enjoying a quiet drive compared to the whirlpool of commuter traffic in the morning. A quick lunch and we were into our heavy shoes for a ninety-minute walk by Ruislip Lido before sunset. It made the perfect finish, walking over a golf course and through birchwoods by the lake before setting off for home. We were back in Gartocharn in time to see the pink of alpenglow flood the flawless snows mantling the Highland hills.

To mark the occasion, S.T.V. decided to show again the very first programme I made in the Weir’s Way series – one that began in my old cottage with me at the typewriter before setting off for a look at Loch Lomond. Little did I know that this film was to lead to several dozen more programmes, and many kind letters from readers of The Scots Magazine and others. For these encouraging letters I would like to say, “Thank you.” It is good to know you have so many friends.

- Tom Weir at Kingshouse, Argyll with the Weir’s Way camera crew

More from Tom

More from Tom

- More instalments every Friday