Tom Weir | Songs of Mingulay

December is perhaps not the best time of year to visit Scotland’s islands, but Tom Weir was never one to turn down an adventure! Here is the report he wrote for The Scots Magazine on his trip back in 1975.

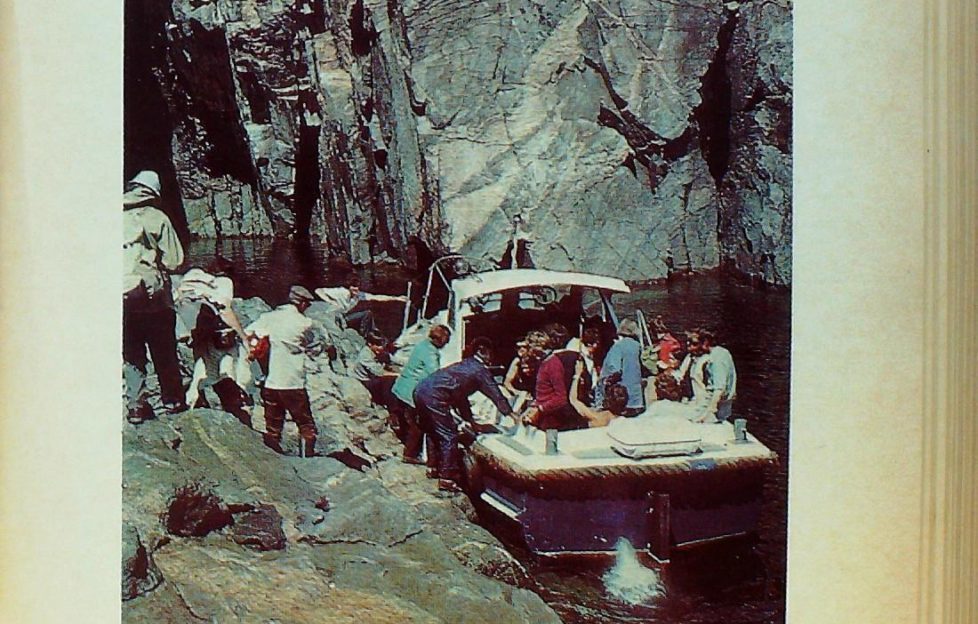

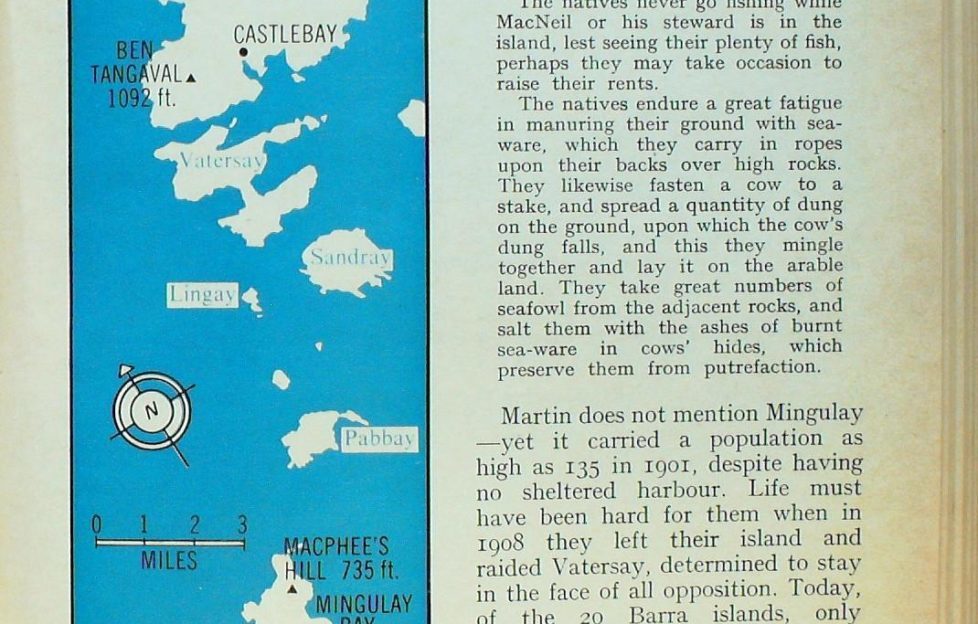

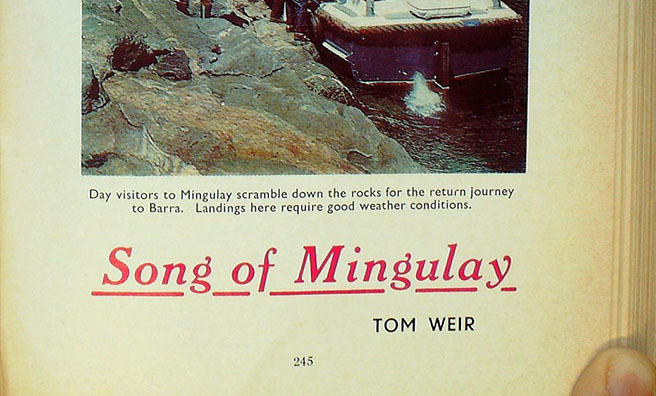

Atlantic islands are a gamble for weather. Now after days of drizzle on Barra we were getting the pay-off, the air cleansed of moisture, and ahead of our fast-moving launch the blue whale-backs of islands, highest of them distant Mingulay where we were going. It was a day excursion, at £3 per head for the full boat-load, and with the sea oily calm everybody was enjoying themselves, watching the antics of cohorts of shags, neck-stretching to look at us with reptilian eyes from their rocks, or thrilling at the diving gannets splashing into a sea bobbing with puffins, razorbills, fulmars and guillemots.

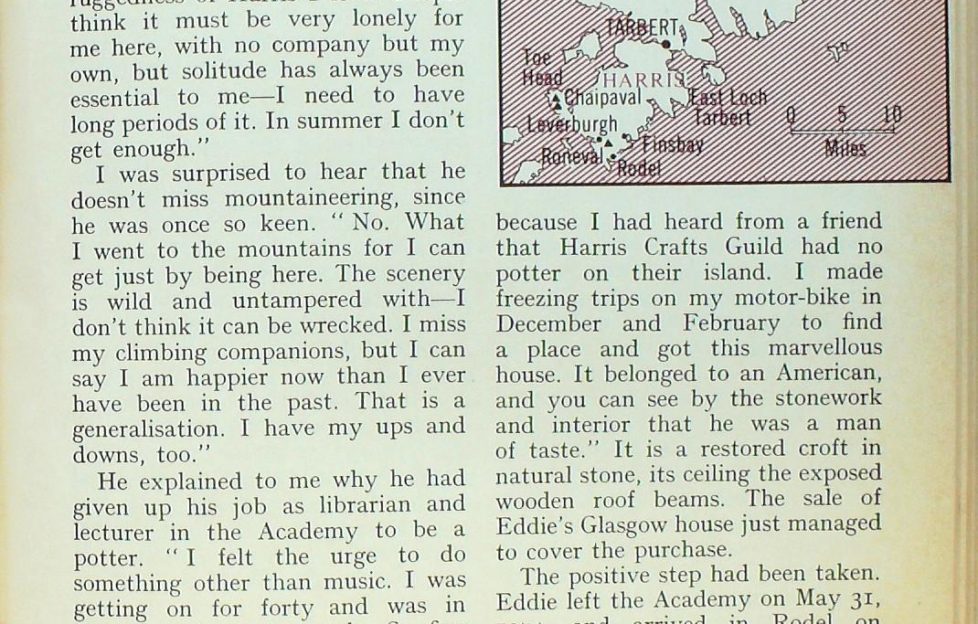

Never a dull moment as Vatersay, Sandray and Pabbay were left behind, and ahead lay green Mingulay a heaving double haystack. In less than two hours we were closing on it, slipping under MacPhee’s Hill to nose into a rocky gully and look on a bouldery shore for a landing.

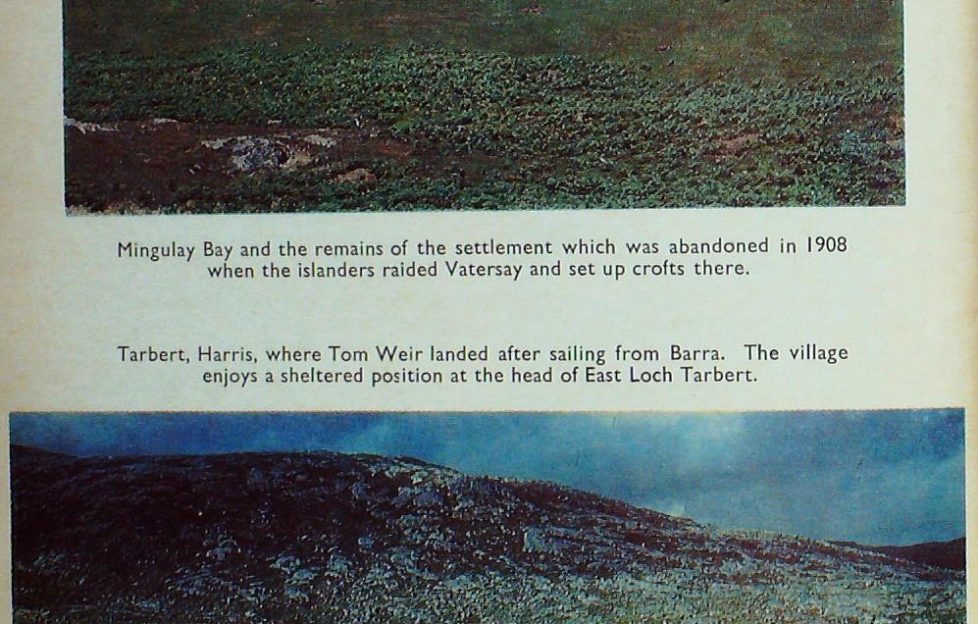

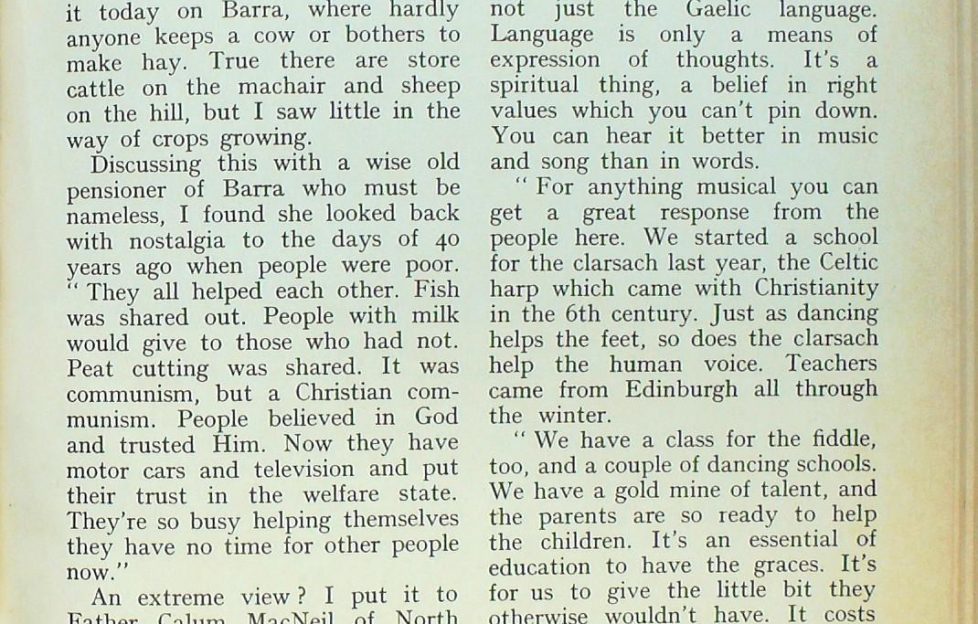

A steep scramble of a few hundred feet, and soon our fellow passengers had dispersed, most of them heading for the white sands of Mingulay Bay and the greensward of fields rising behind the ruins of the former village. With time so limited, we decided to keep our height and head up the highest hill. I wanted to look down the edge where it plunges vertically into the sea for I had heard that its 750-foot drop rivals anything on St Kilda. No doubt about it — it does, and is all the more dramatic for the way it heels over from an overhanging green edge of cornice. Jump off there and you wouldn’t touch anything as you passed the growling guillemots and yelling kittiwakes thronging the lower ledges. Only the fulmars can use the tiny ledges on the vertical upper face. Here indeed is a challenge to sea-cliff climbers. I shall be telling Hamish MacInnes about it when he returns from Everest.

The Island of the Dead

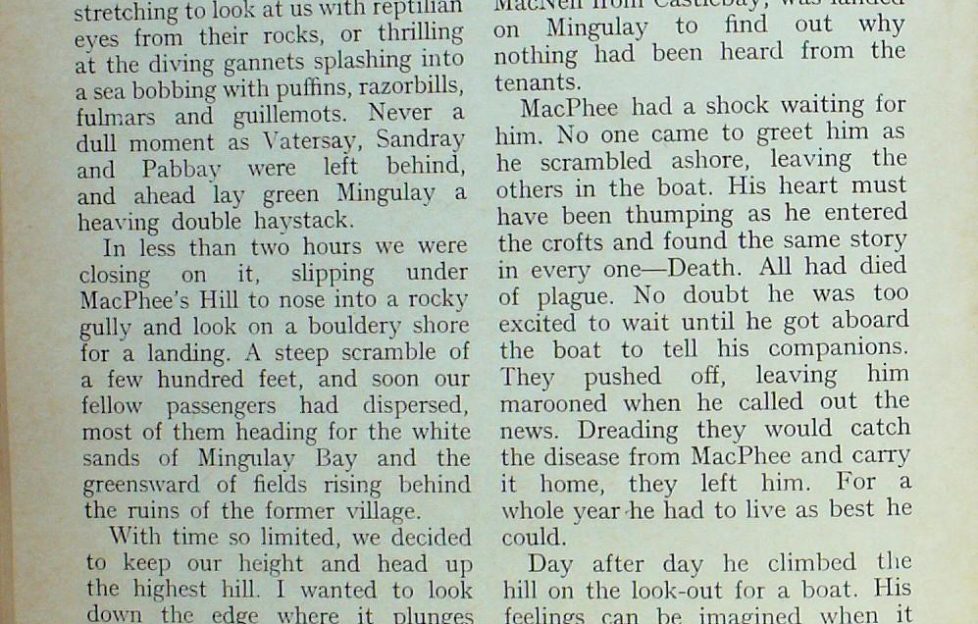

Just across from us and over the gap lay the round summit of MacPhee’s Hill. What I had not realised until that moment was that when MacPhee was marooned on Mingulay he could actually see the houses of Castlebay from the top of the hill during his whole year on this island of the dead. The story is an incredible one. MacPhee, one of a boat crew sent by the MacNeil from Castlebay, was landed on Mingulay to find out why nothing had been heard from the tenants. MacPhee had a shock waiting for him. No one came to greet him as he scrambled ashore, leaving the others in the boat. His heart must have been thumping as he entered the crofts and found the same story in every one — Death. All had died of plague. No doubt he was too excited to wait until he got aboard the boat to tell his companions. They pushed off, leaving him marooned when he called out the news. Dreading they would catch the disease from MacPhee and carry it home, they left him. For a whole year he had to live as best he could. Day after day he climbed the hill to look out for a boat. His feelings can be imagined when it came at last. I would love to know more about MacPhee, but I have found out nothing, except that he was given land on Mingulay when it was resettled by crofters who were also wildfowlers. From where we stood we could see one of the big rock stacks the islanders climbed, Lianamul, a veritable fragment of St Kilda. Up along the edge of the cliff, a short rise and we stood on the summit crest of Mingulay at 891 feet, with nothing south of us except the hump of Berneray crowned by the Barra Head Lighthouse on its western crest. It was hard to realise there was nothing beyond but ocean stretching 2000 miles to Newfoundland and Labrador. The lighthouse stands above a 600-foot drop, a cliff where the seas break with such violence in storm that fish thrown up are sometimes blown upward to land on the grassy top round the light. No one lives on Berneray now, yet it carried a population until 1931 when it was down to six. According to Martin Martin, Berneray excelled for the quality of its cultivation and fishing. Here he is writing in the 17th century:

The natives never go fishing while MacNeil or his steward is in the island, lest seeing their plenty of fish, perhaps they may take occasion to raise their rents. The natives endure a great fatigue in manuring their ground with sea- ware, which they carry in ropes upon their backs over high rocks. They likewise fasten a cow to a stake, and spread a quantity of dung on the ground, upon which the cow’s dung falls, and this they mingle together and lay it on the arable land. They take great numbers of seafowl from the adjacent rocks, and salt them with the ashes of burnt sea-ware in cows’ hides, which preserve them from putrefaction.

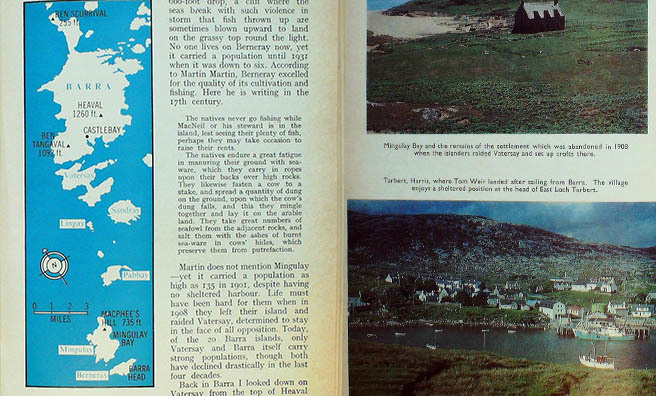

Martin does not mention Mingulay —yet it carried a population as high as 135 in 1901, despite having no sheltered harbour. Life must have been hard for them when in 1908 they left their island and raided Vatersay, determined to stay in the face of all opposition. Today, of the 20 Barra islands, only Vatersay and Barra itself carry strong populations, though both have declined drastically in the last four decades.

The Scottish public raised their voices…

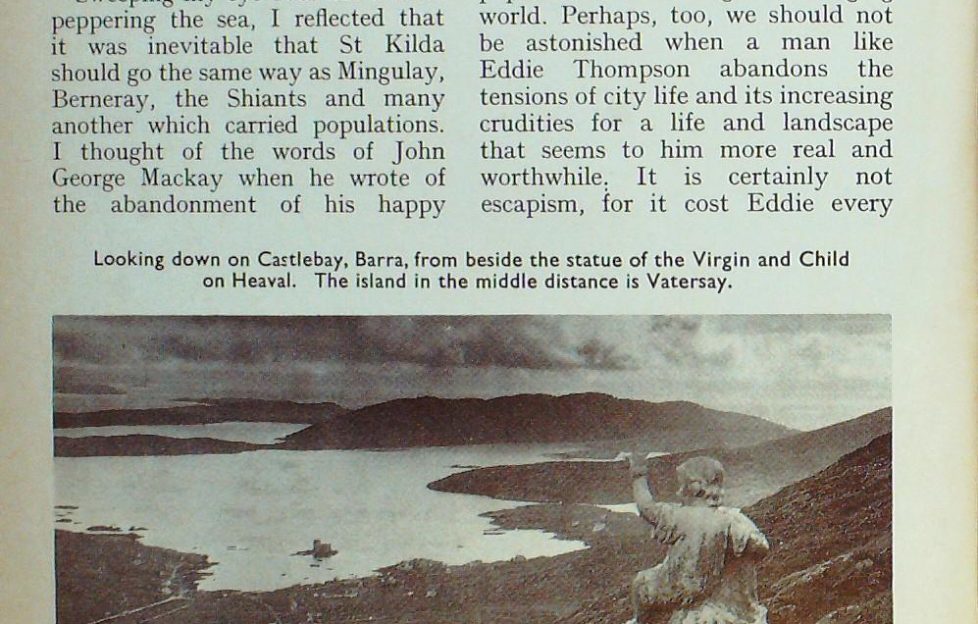

Back in Barra I looked down on Vatersay from the top of Heaval (1260 ft), a winged island connected by a narrow body of sand. Looking down at the Swedish-style timber houses I thought of the bold action of the Mingulay raiders, and of the ten who went to Calton Jail in Edinburgh for the cause. They proved their point. The Scottish public raised their voices in support of the squatters—no doubt to the consternation of landowner Lady Gordon Cathcart, who wanted rid of the raiders. The Government solved her problem by buying her out and allowing the squatters to become crofters. Sentences for those jailed were reduced from six months to six weeks. There was enthusiasm for crofting then. There is little enthusiasm for it today on Barra, where hardly anyone keeps a cow or bothers to make hay. True there are store cattle on the machair and sheep on the hill, but I saw little in the way of crops growing. Discussing this with a wise old pensioner of Barra who must be nameless, I found she looked back with nostalgia to the days of 40 years ago when people were poor. “They all helped each other. Fish was shared out. People with milk would give to those who had not. Peat cutting was shared. It was communism, but a Christian communism. People believed in God and trusted Him. Now they have motor cars and television and put their trust in the welfare state. They’re so busy helping themselves they have no time for other people now.” An extreme view ? I put it to Father Calum MacNeil of North Bay. He listened with a humorous twinkle in his eye. “The people who live in these islands are realists. You live in an industrial society; so do they. Their expectations are the same. Long ago one had to exist on what the croft could produce. There was no alternative when I was young. There is social security today. If no work is available on Barra, you go and find it on the mainland, or go to sea. Then you come back with stamps on your card and draw your benefit. It’s the way society works, on the mainland as well as on Barra.

There is a mystical element, which keeps these island communities together

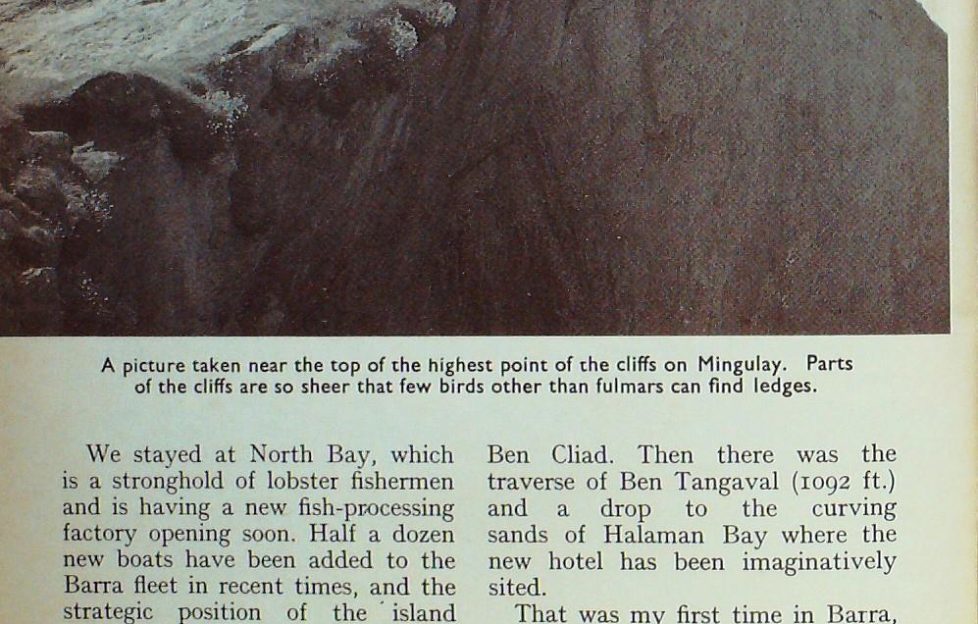

Maybe we should be thanking God for the recession, for it can teach us all a lesson in real values. As for neighbourliness, it is still a virtue of the people here—maybe not as much as it was. There is a certain amount of materialism, but there is also a mystical element, which strengthens and keeps these island communities together. It’s not just the Gaelic language. Language is only a means of expression of thoughts. It’s a spiritual thing, a belief in right values which you can’t pin down. You can hear it better in music and song than in words. “For anything musical you can get a great response from the people here. We started a school for the clarsach last year, the Celtic harp which came with Christianity in the 6th century. Just as dancing helps the feet, so does the clarsach help the human voice. Teachers came from Edinburgh all through the winter. “We have a class for the fiddle, too, and a couple of dancing schools. We have a gold mine of talent, and the parents are so ready to help the children. It’s an essential of education to have the graces. It’s for us to give the little bit they otherwise wouldn’t have. It costs money, but we can raise it. The clarsachs cost £200 each and we should have six this winter. We have a bagpipe school, too.” I left the realistic priest of North Bay feeling less pessimistic about the future of Barra and Vatersay, especially when I saw new croft houses being built and heard that the population was slowly rising. It is 1200 at the moment, but Father MacNeil would like to see it at 2000. We stayed at North Bay, which is a stronghold of lobster fishermen and is having a new fish-processing factory opening soon. Half a dozen new boats have been added to the Barra fleet in recent times, and the strategic position of the island places it well for further fishing developments. The Highlands and Islands Development Board and other authorities are fully conscious of this potential, and want to promote it. Plenty of rock for scrambling up at this north end, on Ben Scurrival where I found myself tip-toeing on vertical gabbro above the sea, enjoying marvellous holds and a view from the summit away to Skye and Rum. The west side was good, too, on the gneiss of The Craig and Ben Chad. Then there was the traverse of Ben Tangaval (1092 ft.) and a drop to the curving sands of Halaman Bay where the new hotel has been imaginatively sited. That was my first time in Barra, and I know I shall be back. Now we ferried north for Harris, enjoying the warm sun in deckchairs as we watched the Cuillin slide past and the grey rocks of East Loch Tarbert draw near. It was a long time since I had sailed in that way, and this was my first landing in Tarbert with a motor car.

Climbing and catching up on Harris

Harris is a big place when you don’t have your own transport, and I remembered the first time we climbed on the Sron Ulladale range we depended on a once-weekly bus. This time we took the narrow switchback to Rodel by the east coast, a journey through the worst land in Scotland for crofting — rock desert all the way. This is the district known as ” Bays ” because there are so many snug anchorages for boats. Apart from a few rigs of potatoes I saw no crops. What we were keeping our eyes open for was a “Caravan To Let” sign, and we found it at Finsbay. We got in just in time before the clouds, which had piled up, discharged good measure. From outside we could hear the guttural barking of red-throated divers as they flighted in a streamlined shape over the bay. It was still bucketing down in the morning, but I had a call to make in Rodel, on a climbing friend by the name of Eddie Thompson who sold up his house in Glasgow 18 months ago to try a new life as a potter in Harris. For 18 years Eddie had worked at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in Glasgow. Then he had given up his post to switch arts and try to become a good potter. I knew I was in for an interesting meeting. Bearded, skipper cap at a jaunt angle and bent over a piece of clay, his face lit up when his eyes met mine as I tapped the window. I didn’t waste many words. “Look, Eddie, this is just a quick call. We’re on our way to the hill, but I’ll come back in the evening and have a crack after supper.” He grinned broadly. “It’s well seen you’re self-employed!” All too well I know how holidaymakers can erode your working time. No need to shift the car, for Roneval rises 1506 feet above Eddie’s house, and as we climbed the waterfalls of the burn the mist was lifting and the rocks beginning to glitter pink as the sun gleamed. Soon we were looking down on gleaming lochs and sunpatched ribs of old lazybeds on their shores, signs of the times when the crofters of Rodel used every patch of possible arable land. Then down came the mist again and the wind felt cold as we approached the first top. On the highest point half an hour later I was beginning to wonder if we were going to be unlucky and land in the middle of another bad spell. Then the curtain began to lift and out of the greyness rose blue waves of hills above billows of gneiss, the Clisham and the blunt nose of Strone Scourst most prominent, summits extending to Tirga More which had given us grand walking and exciting rock climbing in other years. Below us, to the south-west the Sound of Harris was sullen and the straggling township of Leverburgh looked bleak and lonely on the edge of the sea. It takes its name from Lord Leverhulme, who had such high hopes when he built it in 1923 to found a fishing empire. Sheds, piers, jetties, roads are still there, but the dream faded with his death two years later. The Harris folk were sorry, for they were behind him and had tasted some of the benefits. Rodel looked cheerier, with the sun on its greenery and the church tower pink above the sea stretching to Skye. The Shiant Isles were there, too, and beyond them I could pick out the Torridon hills, Slioch and An Teallach. I thought I had identified everything, then suddenly on the horizon westward I picked out the dark humps of St Kilda, with slim rock stacks like exclamation marks on the flank — a thrill indeed to see them a full 10 hours and more by fishing boat from here. On my first trip to St Kilda I sailed from the Sound of Harris in the Scalpay boat Amaghdean Herrich to spend a marvellous fortnight in the sun. Every day had magic on a Hirta which was then exactly as the islanders left it, apart from the falling-in roofs and the Soay sheep wandering in the empty fields. My next visit was with the Army in a landing-barge after it became a rocket-tracking station.

“Each day is a joy and every journey a delight in this place”

Sweeping my eye over the islands peppering the sea, I reflected that it was inevitable that St Kilda should go the same way as Mingulay, Berneray, the Shiants and many another which carried populations. I thought of the words of John George Mackay when he wrote of the abandonment of his happy isle, Eilean nan Ron in Sutherland: Education was advancing, and having been all over the world during the war years, the younger generation had been given an insight into what was going on elsewhere, and that sealed the doom of the island. It was the same all round the north and west coast . . . Fishing and crofting as their forefathers knew it was reduced to a shadow of what it used to be. Perhaps we should be astonished that these islands held on to their populations for so long in a changing world. Perhaps, too, we should not be astonished when a man like Eddie Thompson abandons the tensions of city life and its increasing crudities for a life and landscape that seems to him more real and worthwhile. It is certainly not escapism, for it cost Eddie every penny he had to settle here. Now it was time for me to find out how he liked it. ” Each day is a joy and every journey a delight in this place. There’s such an incredible richness of rock textures. All I have to do is look out of a window to feel enjoyment. Through that porthole I can see the Cuillins, and in the sunny days of March in snow, they were alpine. Even in bad weather there are the seascapes. It’s the ruggedness of Harris I love. People think it must be very lonely for me here, with no company but my own, but solitude has always been essential to me—I need to have long periods of it. In summer I don’t get enough.” I was surprised to hear that he doesn’t miss mountaineering, since he was once so keen. “No. What I went to the mountains for I can get just by being here. The scenery is wild and untampered with—I don’t think it can be wrecked. I miss my climbing companions, but I can say I am happier now than I ever have been in the past. That is a generalisation. I have my ups and downs, too.” He explained to me why he had given up his job as librarian and lecturer in the Academy to be a potter. “I felt the urge to do something other than music. I was getting on for forty and was in danger of becoming stale. So five years ago I went to the Glasgow School of Art and did two years sculpture and three years at pottery. It’s a creative thing, like music. I felt I could fulfil myself in it, and when my teachers showed belief in me and advised me to get a studio I began to think seriously about it. “I might have set up in Glasgow had it not been too expensive. I came looking for a place here because I had heard from a friend that Harris Crafts Guild had no potter on their island. I made freezing trips on my motor-bike in December and February to find a place and got this marvellous house. It belonged to an American, and you can see by the stonework and interior that he was a man of taste.” It is a restored croft in natural stone, its ceiling the exposed wooden roof beams. The sale of Eddie’s Glasgow house just managed to cover the purchase. The positive step had been taken. Eddie left the Academy on May 31, 1974, and arrived in Rodel on June 1. “I hired a removal van. My climbing friends helped me pack my kit. We drove up, got the stuff unloaded, then away they went back to Glasgow with. the van—the ferry charge for it was £90 by the way. ” Without them I don’t know what 1 would have done. I still had a pottery to build—and they did all the detailed planning. One was an architect, another an engineer, and John McLeod of Broadford—the only native to have done the Cuillin Ridge in a day— was the builder. John came over in November and put up the pottery in nine days, walls, roof and fitting of the kiln. I got started work in January, at last.” I raised the financial question. Was he winning or losing ? ” It’s very satisfying, I’m actually supporting myself on my sales.” Eddie has a racy turn of speech. “Yes, I’ve had Hamburgers, Frankfurters and Heidelbergers and Berliners and Stuttgarters and Amsterdammers and Nice people and Mentonese, and Parisians and Londoners and Glaswegians and Edinburghers and even a native of Benbecula, and many others, from New Zealand and America and Canada. They’ve all bought pots and carried them back to Hamburg, Frankfurt, &c., &c., &c. ” As for climbers, I’ve had a constant stream of them, and very useful they are, too, for cutting peat, chopping wood, cooking, and even carrying pots for me back to the big city. I’m opening the kiln tomorrow morning, by the way, and I’m dying to see how the things inside have come out. I’ll wait until you come.” Eddie’s excitement was marvellous to behold when I returned to see the big moment, which began with a gradual opening of the kiln door to let the cold air seep in gradually. Meantime, Eddie, peering inside gave a running commentary of his impressions of what work he could see. As a photographer, I felt it was rather like being in the darkroom watching with excitement the moment when a looked-forward-to print takes shape in the developing dish. Eddie likened the moment of seeing your finished products to the making of music in creative satisfaction. That moment came when the door was swung open and out came piece after piece, bowls, ornamental plates, art-objects, table lampstands, &c. When I admired the richness and colour of the glaze on some of them, his eyes lit up. ” It’s going to be wonderful to experiment with the local rocks, there is so much here. Oh, you don’t know how glazes can become a lifetime obsession with potters!” He explained that when you grind down the rock and apply it to the outside of the finished ” pot ” and give it heat treatment in the kiln, the clay and the veneer become one, with wonderfully enriching colour effects heightening any design that may be on the ” pot.” ” Pottery is as old as music,” he said, as he got down to work, rolling pieces of clay between his palms to begin building a new piece. As yet he does not use a wheel. “You could call mine sculptural pottery,” he explained. ” I never know what shape I’m going to make when I start. It just comes out as I go along. I’ll be doing some other things when my wheel arrives, pottery for utility use in the kitchen and dining-room.” And he combines the two most ancient of crafts, for at his work he has a constant background of music. Mozart, Brahms and Chopin and Bach are his favourite composers. Eddie wears a hearing aid and has to listen hard and hp read to hear the human voice, but the resonance of music he can receive perfectly. Nor was he shy about giving me some music on the piano before I left, playing with unselfconscious pleasure and professional skill.

You have the feeling of “belonging” on an island where all destinies are shared

We left him to drive to Northton and take a walk to the top of Chaipaval (1201 ft.), look down on Toe Head and the wonderful yellow-sand beaches of this western side, in such startling contrast to the rocky east. Back along the sands we had the company of dozens of ring plover, dunlin and a quartet of elegant greenshanks. Then off we drove north, stopping at a croft to buy gooseberries, potatoes and a lettuce. The crofter was an Irishman. “I was in the Middle East for a while, and I got a bit tired of being shot at. I looked for a quiet spot when I got back, so I came here. I have a milking cow and store cattle. I grow vegetables, and I planted these trees as a shelter-belt. See how well they’re growing. I’m living in a caravan for I’ve let the house for the summer. This life will do me. It’s good. Cheerio, friend!” North across the hills and into Lewis we found the crofters haymaking. We could hear the clack of looms, too, but the general news of the tweed industry was bad, the mills just ticking over and talk of reorganisation. The future of the textile industry in Lewis would appear to lie with the double- width loom, which would put the weavers into communal sheds using power instead of treadling with the feet. Optimism centres around oil-related developments now taking shape at the mouth of Stornoway harbour. Young men are being trained in fitting and welding for the £8 million fabrication and engineering works of Fred Olsen, Ltd. It is expected that over a thousand men will be employed by 1982, which is a boost to an island which has always had a top rating in numbers of unemployed. Stornoway was a much busier and more prosperous place than I remembered it. I was glad I had seen it again before the big engineering operations get under way. We sailed past the steel skeletons of the big prefabrication sheds as we headed east for Ullapool in the rain. Back on the mainland life seemed, somehow, dull after these islands. I think I know how the St Kildans felt when they left and found not the Utopia they imagined, but a world they found bewildering. You have the feeling of “belonging” on an island where all destinies are shared. Check back here next Friday for the next instalment from Tom’s Archives…

More from Tom’s Archives

- December 1975: Songs of Mingulay