Starlings In The Roof – Jim Crumley

Jim Crumley has a run-in with a white van man on the subject of Starlings and looks at how they have recolonised the Scottish mainland.

EVERY SPRING I have starlings in my roof. They use a gap where a couple of tiles have slipped at the front of the house. They cart truck-loads of vegetation inside, which must add considerably to the depth of insulation already in there.

At the end of every winter, some passing roofer touting for work will point out the hole. He will shake his head at it with a worried expression then quote me a price to fix it. I nod sympathetically and say I’ll think about it and call him back. And I never do because I know that in the next month or so, the starlings will come prospecting. I like starlings and I like having them around.

And by now I know that I should have the roof fixed. And by now I also know better than to explain to him why I haven’t had it fixed. I tried once and was lectured for five minutes about the damage that starlings can do. What pests they are, and they’re noisy and smelly and messy. Why I was paying council tax just to accommodate starlings? When he’d stopped I told him I didn’t just accommodate starlings: there were sparrows in there too, although they don’t use the starling entrance but can sneak in under the tiles higher up the roof.

‘Super Bird Xpeller PRO’

I discovered very recently that white van roofer man is not alone in his contempt of starlings. Did you know there are websites devoted to getting rid of starlings? One of them will sell you a Bird Xpeller PRO. Or, if you’re peculiarly infested by the rabid droves, a Super Bird Xpeller PRO. These are sonic devices that mimic natural predators and “bird distress cries including starlings”. What is not explained is how the manufacturers of these wretched things think that listening to recordings of starlings in distress is preferable to listening to the actual undistressed starlings. You can also buy a thing called a Prowler Owl that “keeps birds and small pests away”. I am amazed by the ingenuity that certain tribes within your species and mine lavish on the process of rubbishing nature.

The starling in Scotland is a Lowlander and an Islander. And, despite the best efforts of the purveyors of distressed starling Xpellers and Prowler owls, they like human company. In fact, mostly, they depend on it. In return, they put on a show. Everything they do has a routine of swagger and dance to it. Up to and including an aerial display that makes the Red Arrows look like the Wright brothers. And everything they do, they do in the company of other starlings.

‘Sprouting strange fruit’

This cocktail of swagger and sociability extends to communal bathing. I found, for example, on the inland edge of the saltmarsh margins of Wigtown Bay, a small clutch of pools hidden among scrubby shrubs and a low frontier of wetland-loving alders. And those trees and shrubs appeared from a distance to be sprouting strange fruit. Closer inspection revealed a glossy crop of sunlit starlings. They were gossiping in a weird mix of creamy vowels and grating gutturals (a kind of linguistic custard and prunes), and vigorously dishevelling themselves.

The trees and a low bank conspired to enclose a small horseshoe-shaped arena whose open end faced the sunlight. There amid rough grass and scraps of reed beds, the pools lay blinking in the low morning sun. It would be hard to contrive a setting more conducive to the diamond-splintering spectacle that is a backlit squad of starlings sharing a bath.

‘Glittering arcs of water’

The pools were small and shallow, they accommodated six, seven, ten, twelve starlings at a time. In the deepest water the starlings waded waist-deep which is more than enough for them to put on a show. They have evolved a technique of deploying their wings to scoop glittering arcs of water a yard in the air. Like waterfalls in a big wind. As these reached their apex and began to fragment and fall back towards the pool the sunlight made of them a confetti of rainbow colours.

The birds tumbled from tree and shrub into the water, while others fluttered up out of the water to low perches. They reorder their plumage before they flew up to the higher branches to begin the dishevelling process of getting dry. Meanwhile, new bathers battered the surface, lobbed their instant rainbows into the air, plunged their heads under to throw water across their backs, surfaced to shake themselves, and generally created merry chaos with undisguised relish.

Two walkers with two dogs appeared. The starlings scattered to the treetops. For all of half a minute they maintained an unbroken stream of sotto voce havers. Then the first bathers clattered back down to the pools and the whole exuberant process resumed.

‘Ornithological folklore’

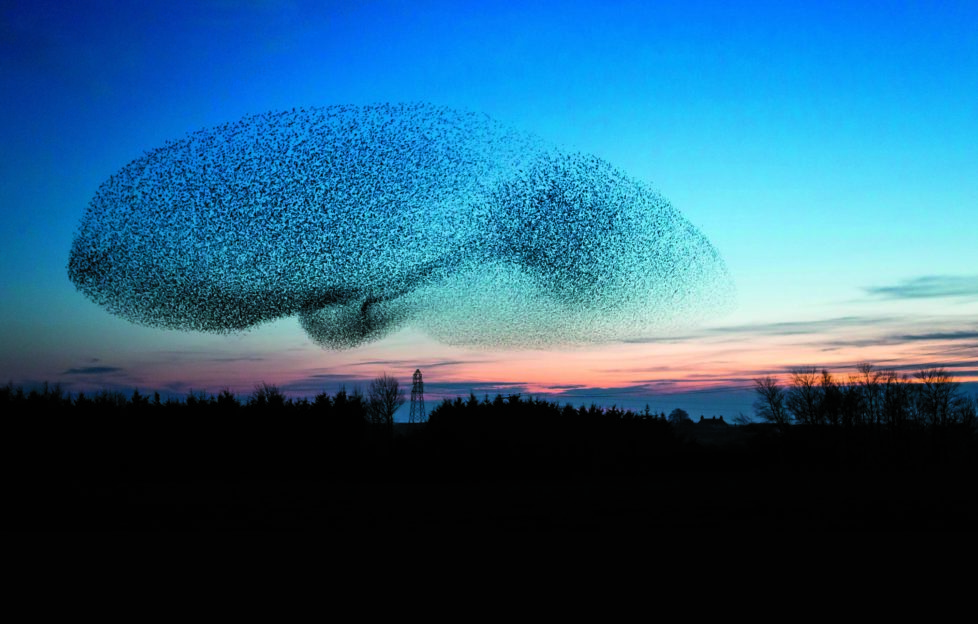

From Wigtown to Gretna, the Solway is a starling landscape, and is rightly famed for those traffic-stopping, jaw-dropping, pre-roost gatherings of autumn and winter birds in their many thousands that float across the sky, billowing and undulating like airy smoke, contracting and expanding like deranged accordion bellows, “a dance to the music of time” in George Mackay Brown’s phrase. Sometimes these gatherings assume such proportions that they have become the stuff of ornithological folklore – 500,000 at West Freugh in 1979. If you have trouble getting your head round what half a million starlings might look like unleashed in the apparently orchestrated choreography of their traditional skydance, you should know that twice now – in 1968 and 2001 – an estimated one million starlings hurtled out from beneath the Tay Bridge at Dundee and rose to unfurl a bird cloud to darken the sunset.

From Wigtown to Gretna, the Solway is a starling landscape, and is rightly famed for those traffic-stopping, jaw-dropping, pre-roost gatherings of autumn and winter birds in their many thousands that float across the sky, billowing and undulating like airy smoke, contracting and expanding like deranged accordion bellows, “a dance to the music of time” in George Mackay Brown’s phrase. Sometimes these gatherings assume such proportions that they have become the stuff of ornithological folklore – 500,000 at West Freugh in 1979. If you have trouble getting your head round what half a million starlings might look like unleashed in the apparently orchestrated choreography of their traditional skydance, you should know that twice now – in 1968 and 2001 – an estimated one million starlings hurtled out from beneath the Tay Bridge at Dundee and rose to unfurl a bird cloud to darken the sunset.

Pondering such profusion, and allowing for the fact that the numbers are swollen by winter migrants from mainland Europe, you would be forgiven for thinking that our country teems with starlings. But their numbers are crashing – an 80 per cent fall in the last 40 years – and they fall still. It is unthinkable that they could vanish from mainland Scotland altogether, except that it has happened before, and they were gone for a hundred years, for almost the entire 19th century. The most likely theory is that a series of prolonged cold winters deprived them of food. A theory given some credibility by the fact that they hung on in the Western Isles and Shetland. There, the milder waters might have mitigated the worst excesses of that sustained freeze that banished the mainland birds.

Recolonisation

One of the consequences of that isolation has been the emergence of a Shetland sub-species with a wider bill and darker juvenile plumage. It is possible at least that the sub-species evolved throughout Shetland, Fair Isle, Orkney and the Western Isles. As starlings eventually began to recolonise the Scottish mainland from England and spread slowly northwards, interbreeding between mainland and island birds diluted the strain everywhere apart from Shetland, where it still survives.

And for the moment I too live in a landscape of starlings, which is my good fortune. From my roof to the fields of the Carse of Stirling to the streets of the old town and the quiet pleats of the Castle Rock and Ballengeich Hill, you will bump into starlings almost everywhere and in various quantities (they hunt in packs) from handfuls to dozens to hundreds, and to autumn and winter dusks in occasional thousands. I like to meet them best out on the Carse with its arc of mountains from Ben Lomond in the west to Ben Ledi in the north-west and Ben Vorlich and Stuc a’ Chroin in the north, and if possible when a midwinter sunset has just submerged and thrown a scarlet afterglow around the snowy pow of Ben Ledi (for it sits at the centre of the arc).

‘The right place at the right time’

It is as if the starlings relish the nature of the stage set at their disposal. On the few occasions when I have been in the right place at the right time, there has seemed to be an extra edge of bravado to the spectacle. Then a thousand birds can look like a hundred thousand.

But my favourite starling moment involved one single bird, and the setting was nothing more memorable than my garden fence. It was one of the roof-nesters. In full breeding plumage it perched on the fence in brilliant sunshine, and it simply dazzled. But there was also a single house sparrow on the fence. It edged sideways along the top spar towards the starling until it was only a few inches away. And there it stopped. Something in its dowdy brown and curved posture with its head slightly lowered suggested an almost worshipful attitude towards the yellow-billed, pink-legged bird-idol in its glowing coat of many colours.

‘My imperfect roof’

I have a photograph of the moment. I should show it to the next white van man that lectures me about my imperfect roof. Just so that he knows what he’s up against.

But it may be that my resistance to getting the roof fixed is finally beginning to weaken. In the last wee while a nearby house had new tiles and a new sealing material fitted to the roof. White van man had pointed this out on his most recent visit, and was eager to point out its efficacy. I was politely making the usual noises when I noticed over his shoulder that starlings were front-pointing up the harled wall towards the apex of the roof, and disappearing inside the sealed edge, and into the roof.

So it begins to look as if technology has caught up with my objections. It is possible to have a roof that keeps the weather out and lets the starlings in. All I have to do now is find the money to pay for it.

You can read more of Jim Crumley’s Scottish wildlife columns

online here, and each month in The Scots Magazine.