Tom Weir | New Friends for the Cairngorms

In August, 1975, Tom explored the Cairngorms with some young hiking recruits

and rediscovered his love of the area through

their eyes . . .

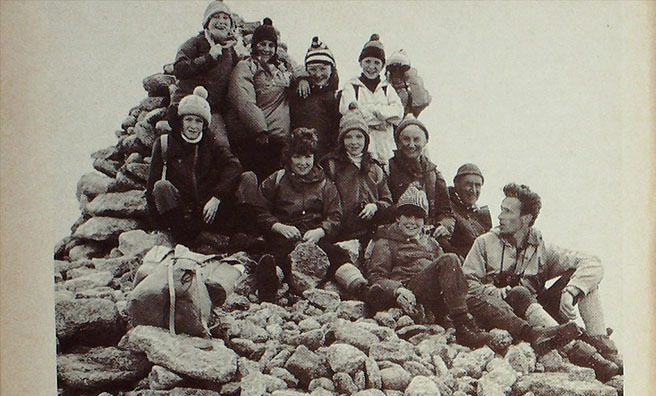

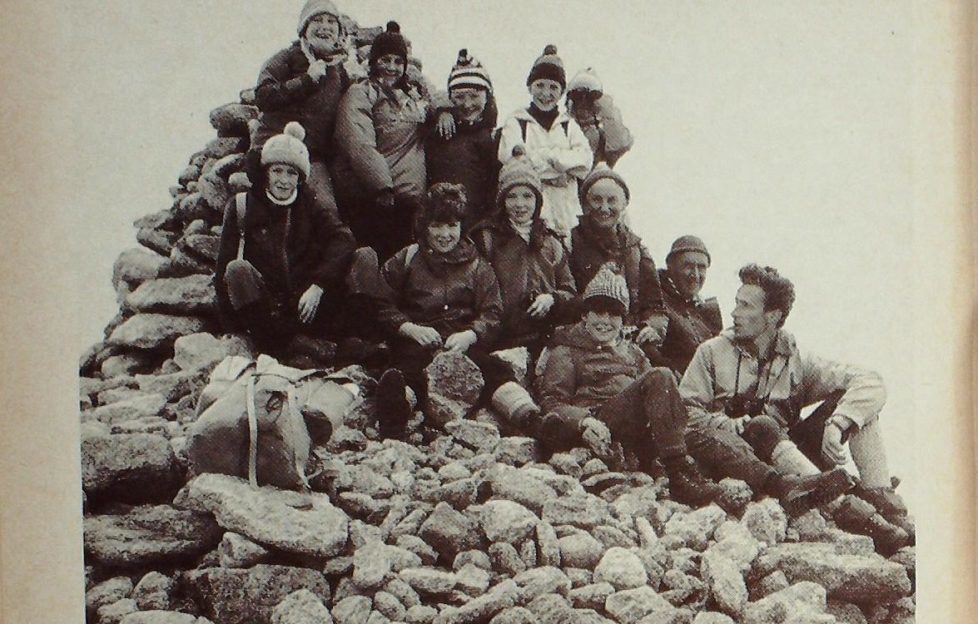

The resilience of 12-year-olds is something to marvel at. I know, for we have just come back from the Cairngorms after a week-end with five girls and four boys. On the first day we took them on an outing to the high tops which should have reduced some of their animal spirits, yet the moment we were back in base the boys declined to rest for an hour before dinner, demanding to go out exploring again with me. All this after a night without sleep and a railway journey from Stirling to Aviemore. Oh, to be 12 years old again !

The inspiration for the trip came from my wife, who felt it would be a great treat for the nine oldest primary children in her school. I vetoed the idea instantly.

“Count me out,” I said determinedly. But she was not to be shifted. She set about things herself, booking a cottage for the week-end, buying rail tickets, arranging transport to Stirling, and organising a minibus from Highland Guides, Aviemore, to meet the train and take the party to their lodgings, then return in the morning with a guide to take an expedition to the high tops.

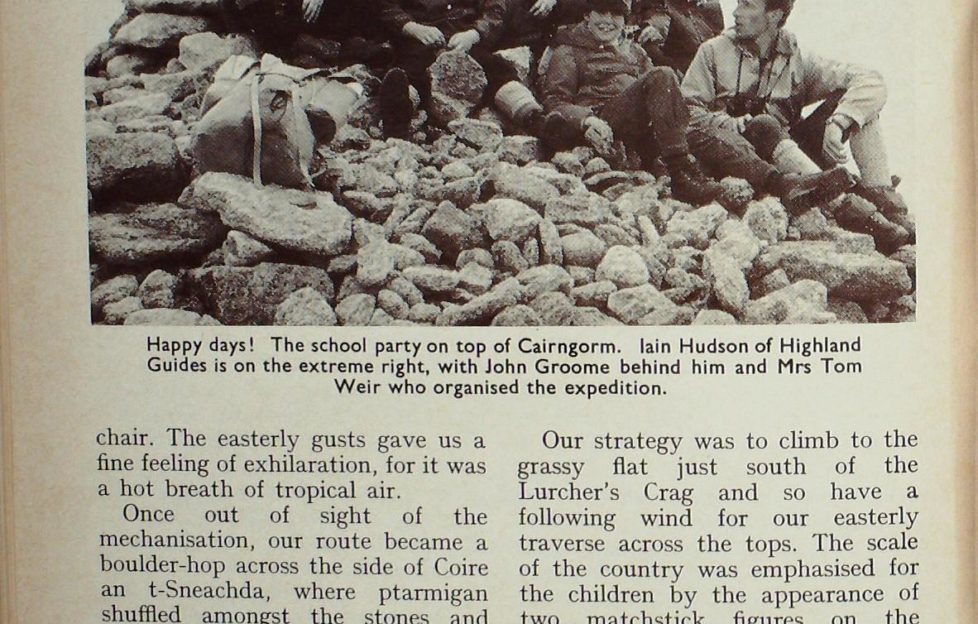

Before I knew it, I was enthusiastic, too, and had agreed to drive up the food and heavy kit. I also invited a spry 68-year-old who loves the hills and has a life-long experience of camping with Boy Scouts. John Groome accepted without hesitation, and was of immediate value; his first job before the children came was to repair the broken water-closet and have the cistern working by the time they arrived.

No sleep that night for those in the hut. The excitement level was too high. John and I fared better, for we had brought our tents. We breakfasted peacefully in the sunshine, but inside the cottage was a fever of noise and activity as “pieces” were made up and bags packed ready for the arrival of the minibus, driven by Iain Hudson, official “guide” for the day.

Iain was a bit concerned about the strength of the wind, which he estimated would be 40-60 knots on the plateau. We had a talk about it, since both of us know that even a summer wind can have exposure effects. Said Iain, “The top chair-lift isn’t working, but we could go into the corries and see what it’s like and take it from there.” It was a sound idea, and off we went.

Glen More was sombre that morning, with branches tossing in the wind and black clouds rolling over the snow-patched peaks. Loch Morlich was sullen with grey waves. Up the ski road to the deserted car park, and there were cries of indignation when we talked about walking from here when the lower chair-lift was working.

We gave way, since the chair-lift seemed to have caught their imagination, and it was fun to watch their uninhibited delight as they were hoisted aloft. Steven, the smallest boy, spotted a red fox on the slopes from the swinging chair. The easterly gusts gave us a fine feeling of exhilaration, for it was a hot breath of tropical air.

Once out of sight of the mechanisation, our route became a boulder-hop across the side of Coire an t-Sneachda, where ptarmigan shuffled amongst the stones and pink creeping azalea was in flower.

Iain told us that the snows of “referendum day” had blizzarded the peaks to winter white, probably destroying the eggs of ground-nesting birds on the high tops.

Over another heathery spur and we were dealing with a burn in white spate rushing down from Coire an Lochan, whose savage rock towers and crevassed snow walls were now close enough to inspire some awe in the children.

Our strategy was to climb to the grassy flat just south of the Lurcher’s Crag and so have a following wind for our easterly traverse across the tops. The scale of the country was emphasised for the children by the appearance of two matchstick figures on the plunging cliff-edge of Coire an Lochan. I explained to them why you have to be so careful on the Cairngorm plateau in mist and snow, because you can so easily step into space over these cliffs.

I also showed them a traversing path from our grassy flat which could take us on an easy walk from where we stood to the Curran Bothy, a hut which had just been demolished and removed by naval cadets of H.M.S. Caledonia.

Naturally, they wanted to know why the shelter was being destroyed, and faces were serious when I told them of the Edinburgh school party in November 1971 who had been unable to find the bothy as darkness fell, and had spent two nights out in a blizzard, resulting in seven being frozen to death on the plateau.

“After that,” I told them, “climbers came round to the opinion that bothies up on the top of the plateau were more likely to lead people into danger than offer safety, for a small dot on the map is hard to find in mist, and in time of snow the bothy may be completely covered over. The demolition party found three feet of ice inside the Curran Bothy.”

Any climber reading this should delete the Curran Bothy, the St Valery and the El Alamein from his map. The probability is that these shelters will be reconstructed somewhere in the lower glens at places still to be decided.

In a way I was glad the conditions were so sombre as we came up the edge of Cairn Lochan to its cairn at almost 4000 feet on the edge of the cliff. No need to tell them to keep away, for they shrank back from the sudden plunge of its dark towers jutting between gullies torn across with black where the snow ribbons had avalanched.

Now you could fully appreciate the vastness of the Arctic plateau spread behind us in undulations of pink granite rising to snow bumps and warty outcrops of granite. Walking west from here, a stranger without a map would get a surprise to find the cleft of the Lairig Ghru between him and the apparently near bump of Braeriach, nor would he have suspected that just to the east lay the trench of Loch Avon beneath the most impressive head- wall of rock in the Cairngorms. The danger of the Cairngorms for the unwary is their apparent simplicity when walking on the tops is so easy.

We followed a broad track in the granite from Coire an Lochan to the top of Cairngorm four kilometres distant, a grand up-and-down traverse of changing rock scenery. At one point we descended for shelter and to look at Coire an t-Sneachda—Corrie of the Snow— where we had the fun of watching a pair of ptarmigan hens scuffling over the boulders on running feet, sparring and tumbling about, then taking off with a “whoosh” of white wings to zoom back and fore on the air currents at high speed.

With excitement the party pointed out a tiny speck of green tent in the corrie floor we had passed on our way to the tops. Dark clouds above us were being whisked away and bits of blue sky appearing. The gale, on which the youngsters could lean at times, had dropped. So, instead of dropping down the Fiacaill ridge as Iain had originally planned, we now offered them the top of Cairngorm as a last prize.

Not all were keen, but John, as our oldest member, made out that he was nearly finished, but set off for the stony rise—a good psychological gambit to encourage the weaker members. In fact, John is a very fit man, and knew what he was doing. Twenty minutes later we were all on top, seeing a very different Cairngorms as pink colours of granite glowed in the sunlight against sparkling snow patches and green water meadows. Loch Etchachan winked behind the black portal of the Shelter Stone Crag, and we rejoiced in the sun shining now from a clear blue sky.

Descending from the summit through the machine-made mess which hits you the moment you leave the north slopes of Cairngorm, I saw all too clearly the damage to the environment that is the price paid for the restaurant and ski-tows above the corrie chairlifts. My fervent hope is that it can be contained here, without further spread in any direction.

By the time we had run down the north-west ridge of the mountain to the car park we were sweltered, and it was hard to believe it was the same day, such was the fierce heat of the sun. So we had a halt at Loch Morlich, while Iain pointed out the whole route to the children, and great was their joy to think they had been over all that high ridge. Then it was back to the cottage to get the spuds on for the mince, and an exploration trip with the boys while things were cooking. They would have been out again after their three-course dinner if my wife had not clamped a compulsory lie-down period on them.

There followed a balmy late evening of last bird song and soft red in the west. Lying in my tent, I found myself going back 35 years to the first time I’d slept at the Shelter Stone when I appreciated as never before the very special quality in the Cairngorms which keeps luring you back. On previous visits I had skirmished over the tops too rapidly. But then I carried four days’ food, tramping in from Coylum Bridge by the Lairig Ghru and the March Burn to gain the plateau.

* * * *

On the climb with the Gartocharn school children I had been asked more than once if anybody had explored all of the Cairngorms, or if there were still bits unknown and undiscovered. I told them the present generation of climbers were continually finding new routes, impossible at one season but possible in another. Also, that old climbers with a lifetime’s experience kept seeing new things they had missed before. That, in fact, no man could exhaust the Cairngorms, or know everything there is to know about even a small part of the range.

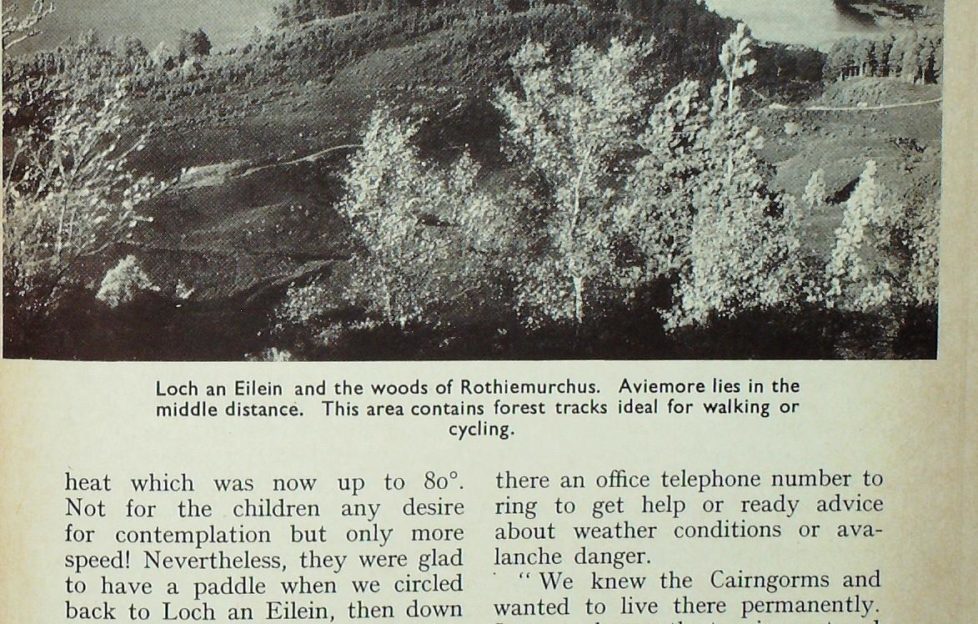

I was glad to take John to one of my own favourite bits next morning, while the kids went with Iain to see the Wild Life Park. It was a heatwave morning, and we headed for Ord Ban, where there was a breeze, and views extending from Ben Alder to the Cromdale hills with the winding Spey as foreground to both, Loch Insh on one side, Loch Pityoulish 011 the other. The wind of yesterday had cleared the air and the world seemed new minted, with the shine on the birches, the pink of the Caledonian pines glowing, juniper scenting the air, and around us a cascade of bird song. On our walk we saw nobody, yet Loch an Eilein was busy with people, and cars by the dozen were parked where there used to be only green meadow.

Our spell of personal freedom was over at 2 p.m., when we were due to meet the main party and take them off exploring the forest on bikes hired from Highland Guides whose base is Inverdruie. Behind us lay Rothiemurchus and its multiplicity of paths, and off we went on the rough tracks of the forest in heat which was now up to 8o°. Not for the children any desire for contemplation but only more speed! Nevertheless, they were glad to have a paddle when we circled back to Loch an Eilein, then down the tarmac road in a streaming convoy to base.

And while they made ready to catch the train for Stirling I had a talk with Iain Hudson about the role of Highland Guides. It is a two-man organisation, formed six years ago when Iain, an aircraft engineer, and Jim Crompton, a farm manager, set up their own information centre. Believe it or not, there was nowhere in Aviemore you could buy countryside books on the Cairngorms in 1969, nor was there an office telephone number to ring to get help or ready advice about weather conditions or avalanche danger.

“We knew the Cairngorms and wanted to live there permanently. So we took over the tennis court and pavilion at Inverdruie, laid in a store of books and hire equipment, and soon proved there was a need for the service we offered. Now we employ seven local staff as part- timers, and we have two outsiders who help. All of our people are qualified on countryside matters, not just in climbing, or hill-craft in summer and winter, but on the bird life, flowers, rocks, trees and the total landform.

“It’s marvellous country—I never tire of it. And there are still corners of it I haven’t seen yet. You could call us non-specialists. For example, we organise ski-touring courses here, using Norwegian skis and lightweight boots, where you don’t need much in the way of technique. Any walker can learn quickly, and in good weather we can tour the plateau on these narrow skis. Bikes are great for natural history rambles in the forest. We started with 10—now we have 30.

“We feel our organisation is just about the right size. We don’t want to become commercial for we’re not in it for profit, but for enjoyment of the outdoor life. The hours are long, but you don’t notice them when you are doing what you want to do. We want to influence folk to care for this environment and see it isn’t ruined by too much commercial pressure. The wilderness keeps shrinking and has to be protected.”

Wise words. The only way to avoid saturation point in areas of high attraction is to plan in such a way that people are channelled to the accessible spots, while the remoter parts are left for those willing or able to get there on foot or ski—no aeroplanes or Land- Rover tracks permitted even to landowners. In a fine new book on the Cairngorms, Dr Adam Watson writes :

Conservationists have no desire to halt all development or to prevent skiers or any other recreational group from enjoying their sport. What they suggest is that every group such as downhill skiers can have most of what they want, without entailing the free-for-all development which would completely spoil the sport or interest of some other group such as

climbers and lovers of wilderness. To achieve this aim, each group will have to give up something of what it would ideally want, but this agreed compromise offers the only hope.

Watson is absolutely right, yet he is alive to the dilemma of everyone who writes about a region he loves. He rationalises as follows :

To write a book which may well attract more people and thus more pressures to these hills is worrying. My sole reason for agreeing was that at present there are obviously not nearly enough of us as guardians to prevent or modify the many undesirable new things which are happening, often with insufficient action to try to control them. The risks I have taken will be justified if this book adds strength to the ranks of the unofficial guardians of the Cairngorms.

Adam Watson’s new book is an entirely rewritten Scottish Mountaineering Club District Guide, by a man who has been exploring them since he was the age of the children on our walk. He was a schoolboy when I first met him in Bob Scott’s cottage at Lui Beg one New Year, and we have spent dozens of days together in the Cairngorm.

A most valuable feature of the new book is the Gaelic names of corries, burns and glens, some of them printed for the first time and resulting from much collecting zeal among locals who still use these names, or knew them in their youth. Adam has been studying Gaelic, even taking part in the annual Mod, and gives his own translation of the fine Cairngorm song, “A lit an Lochain Uaine”, written by the deer poacher William Smith about his bothy eyrie high on Derry Cairngorm.

If you are looking for a good reference book you will find nothing better than this one, written from knowledge and love of one of Scotland’s finest areas.

For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.