Tom Weir | Blackcock Ritual, A Shepherd’s Life and Cat’s Company

In July, 1975, Tom camped out in Glen Lyon, learned that sheep are not quite as stupid as he thought, accompanied a cat down the Loch Insh road, and heard a local dispute over canoeing rights in the Spey.

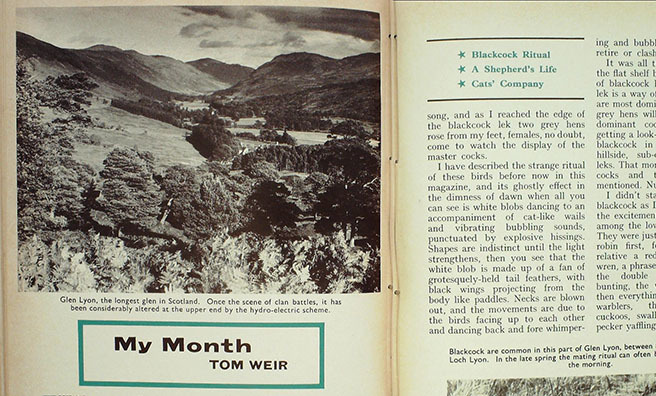

There is a marvellous state of tiredness after a long summer day on the hill when you go to bed and every bone and muscle falls into place whichever way you lie, and you are blissfully comfortable. So it was with me, for I had been up at half-past three that morning watching blackcock on the lek, strolling about listening to the dawn chorus, then exploring a pinewood amongst the red deer before setting off for the 3000-ft. tops to look for dotterel. All this in Glen Lyon, at its most superb in the brilliance of newly-leafing oak and ash, with primroses still blooming in the shady places and bluebells scenting the air. Lamped by a burn in a secret place below the blackcock lek, it was no hardship getting out of the warm sleeping-bag, for there had been no darkness, only wisps of mist settling in the hollows in the moonlight. The first sounds to break the silence as I left the tent were oyster-catchers, a few single pipes at first, then a great shrilling. Next a wheatear gave a jangled snatch of song, and as I reached the edge of the blackcock lek two grey hens rose from my feet, females, no doubt, come to watch the display of the master cocks.

A Strange Ritual

I have described the strange ritual of these birds before now in this magazine, and its ghostly effect in the dimness of dawn when all you can see is white blobs dancing to an accompaniment of cat-like wails and vibrating bubbling sounds, punctuated by explosive hissings. Shapes are indistinct until the light strengthens, then you see that the white blob is made up of a fan of grotesquely-held tail feathers, with black wings projecting from the body like paddles. Necks are blown out, and the movements are due to the birds facing up to each other and dancing back and fore whimpering and bubbling as they advance, retire or clash head-to-head. It was all there that morning on the flat shelf before me. Close study of blackcock has revealed that the lek is a way of showing which cocks are most dominant, and that all the grey hens will be mated by a few dominant cocks, the others not getting a look-in. I have seen eighty blackcock in this single area of hillside, sub-divided into several leks. That morning I saw only eight cocks and the two grey hens mentioned. Numbers are down. I didn’t stay too long with the blackcock as I did not want to miss the excitement of the dawn chorus among the lower trees of the river. They were just starting up at 4 a.m., robin first, followed by its near relative a redstart, the trill of a wren, a phrase from a missel-thrush, the double note of a reed-bunting, the whooping of peewits, then everything was going—willow-warblers, thrushes, blackbirds, cuckoos, swallows, a green woodpecker yaffling, and all the rest. Sheep and their lambs in little groups of fifteen or more were lying down as I passed. So were the red deer stags in velvet in the Caledonian wood. From the crags above I could hear the whee-whee of a ring-ousel. Time for me to go back to the tent, have a snooze before breakfast, then go off with my wife to the hill. The sun was so hot now that I was vaguely regretful at not having begun climbing at dawn, a feeling dispelled above 2000 feet in a cooling breeze which put life into our steps as we came into the realm of golden plover and ptarmigan near the top of Cam Gorm (3370 ft.). Fine, high-level walking leads from here to Cam Mairg, and views are wide, to Glencoe and over Loch Rannoch to Ren Alder, then eastward to the Cairngorms, all of them considerably snow-patched. The Ben Lawers range, by comparison, was bare, but rises very nobly from this side.

…no other corner of the Central Highlands is so enchanting

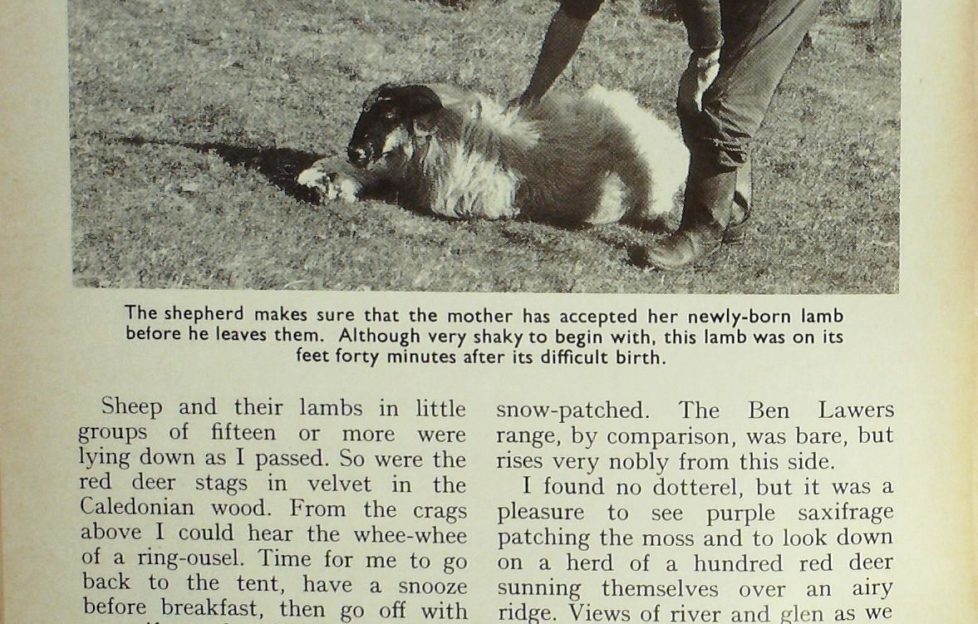

I found no dotterel, but it was a pleasure to see purple saxifrage patching the moss and to look down on a herd of a hundred red deer sunning themselves over an airy ridge. Views of river and glen as we descended confirmed my view that no other corner of the Central Highlands is so enchanting, in variety of woodland and boldness of form. Nor do I know any hills with so many ruins of summer shielings on high flanks on both sides of the glen. Shades of more populous times in the past in the time of the cattle when Glen Lyon held a large Highland community. We headed for home, but there was one call to make on the way and that was on Dougie Jackson at the head of Glen Buckie. I wanted to say cheerio to him before he retired from the hill after 46 years shepherding, for many a good crack we have enjoyed. Only a week before I had been watching him in action when I happened to notice a ewe gyrating strangely, obviously in trouble. Then as I focused my binoculars on it I saw what was the matter. It was giving birth to a lamb but was in difficulties. I knew I had to fetch Dougie or the lamb might be smothered. Luckily he was at the house, and within moments he was off with the dog and two teenage lads. Our full complement was needed to corner and catch the ewe. Then Dougie slipped his hand behind the lamb’s neck, found its forefeet just inside the ewe, and with a turning motion pulled out the slippery, wet shape of the lamb. Instantly his hand was in the mouth of the lamb, straightening the tongue which had been pulled to the side, then, clearing its nose and mouth, he squirted milk from the swollen teats of the ewe into the lamb’s throat. He feared it was dead at first, but then, slowly, life came into the inert body and the ewe’s nose was brought down to the lamb so that she could smell her off¬spring for several minutes. “Let go, gently,” Dougie told the boys as we backed away, leaving the mother who almost at once began licking the lamb all over. “Now she’ll tak tae it, and if it’s a guid tup lamb we’ll ca it Tom,” Dougie smiled. Forty minutes later, from a concealed vantage point, I watched the lamb get on its hind legs for the first time, successful at last alter many topples, some of them due to the mother whose constant licking and nudging had knocked the lamb over time after time. I noticed, however, that every time the lamb tried to suck, the ewe moved away. I told Dougie about this. “Och, aye, but it’ll be managing a wee suck noo and again. That’s a that’s need it tae begin wi.” I mentioned to Dougie about being out in Glen Lyon early in the morning and finding the wee groups of sheep asleep with their lambs. “Aye, ye’ll find a sheep wi its pals. Even at the clippin time they’ll wait and bleat for their pals, then go away quite happy once they’re a thegither. Even when a hogg has been away for the winter, it’ll go right back tae where it was lambed. And it’ll find its mother.” I hadn’t thought about sheep being in family groups, or the importance of the ewe-lamb bond. “Oh, aye.” said Dougie, “the lamb learns a lot from its mother. When you work wi sheep you know they’re no sae stupid.”

There’s a lot more to shepherding than aimless wandering

In my more ignorant days I used to wonder what a shepherd actually did on the hill, since a lot of the time he seems to be walking around aimlessly. In time I learned. Out at dawn in the lambing, he climbs to the tops, moving sheep down into the glen as he goes, the object of it being to spot any sheep that can’t move, maybe a ewe on its back which can’t get up, or a lamb stuck in a drain. A man like Dougie with a trained eye will pick out any ewe that needs help to give birth, or he may take a twin or a triplet from one ewe, carry it home and give it to another ewe that has lost its own lamb. In the afternoon he moves them back uphill again. “Right from when I left school I wanted to work wi sheep. I’ve been a cattleman, too, but I prefer the sheep. Every season’s different, and this has been a guid yin, plenty o grass and the yows in milk. There’s a lot of pleasure in it for a shepherd. To dae the best ye can for them, and be oot as much as ye can and see that things are right. I couldnae dae wi any animal suffering if I could help it.” Times have changed since he started 46 years ago, when wages were low and a shepherd had a flock of only 500 sheep to look after. Nowadays a shepherd must manage 1000 hill sheep for it to be economic, which means the stock itself has to be vigorous and hardy enough to live out on the hill with the minimum of management. So stockmanship is everything. From every batch of lambs you keep selecting the best for your future breeding stock, and so get the ideal animal for your type of ground. The best ewe lambs of this year, as other years, will be wintered away as hoggs, and will not be used for breeding until they are gimmers at a year and a half old. Then, in their fifth year after four lambings, they will be sold as cast-ewes, too old for the hills, but suitable for breeding on low ground. The September sheep gathering is done to pick out the cast-ewes. Jobs to be done before then are the July clipping and dosing for worms, then a big gathering for the lamb sales in August. Last of all is the October gathering for the winter dipping, to waterproof the coat and prevent vermin. And at the same time the sheep are dosed for liver fluke. “In winter,” said Dougie, “you don’t have to worry so long as the sheep are digging and scraping. It’s when they stop you have to start carrying food to them, for it means they’re getting weak.” Good hill shepherds need to have a combination of the stamina of athletes and the dedication of ward sisters in hospitals. In addition they have to be something of midwife and veterinary surgeon in a seven-day-a-week practice. Now 60, Dougie feels he needs something easier, so he is taking up the spade and becoming a gardener. “I’ve always liked gardening,” he said with a twinkle in his eye. “And think of the time I’ll have oft at week-ends. I might even manage to keep a few sheep!” “I think it very likely,” I replied as I wished him luck.

The company of cats . . .

My own luck with the weather was still holding when, after a meeting at the Countryside Commission H.Q. near Perth, I drove north to Kincraig, arriving at dusk just in time for a walk behind the climbing hut. In there I had two odd coincidental encounters with cats. The first one was a big ginger torn treading the high top of a drystane wall. At the sight of me, down it sprang, came over tail in the air, purring loudly, and when I put my hand down to it, started to play, rolling over on its back and catching at my leg when I moved. It came with me on the walk, waiting patiently while I made a cautious approach to five roebucks and two does feeding on the edge of the wood. Then I lost it, but lo, there was a replacement: a black kitten whose delight in my company was enchanting as it chased around, darting at my shoe, playing with my fingers, dancing in the air and even climbing up my knickerbockers. It must have come a full mile down the Loch Insh road with me. Strangely, too, we met the ginger cat, which showed not the slightest interest, but stood like a statue in the half-dark at the side of the road. Only once before have I been accompanied by a cat on a walk and that was in Ardnamurchan with Adam Watson, when a white cat followed us from Faskadale to the top of Meall nan Con (1433 feet), and two miles from the nearest house. It was a crafty cat, for now and again it begged a lift, and perched, purring, on a shoulder, changing porters from time to time. We enjoyed its company until we reached the windy top, at which it went underground and refused to appear from amongst the boulders. Finally we coaxed it out, but clearly it didn’t like the strong wind and down it went again into another deep hole. Again we had to await its pleasure, and this time we had an open rucksack ready, crammed it inside with difficulty, and carried it down to where we had found it. Next day I was on Loch Morlich-side by midday, having a snack among the pines before heading for Loch an Eilein for a favourite little expedition of mine over the top of Ord Ban and away from the nature trail throng. Too many motor cars have churned up the once attractive sward at the Nature Conservancy’s interpretation centre, with the result that this is now to be tarred and a paying meter installed. There is also a toll on the ski road from Loch Morlich to Coire Cas, payable if you spend more than an hour and a half up there. This supersedes the old car parking system, so it is not so iniquitous as it sounds. This summer an extension of the ski tow will take mechanisation farther up Coire Cas. Down at Loch Insh, before departing, I had a chat with Clive Freshwater. I wanted to congratulate him on his victory over Knockando Estate, who tried to prevent canoes of Clive’s school at Loch Insh using the Spey. It is a limited victory, Clive explained, in that it does not establish the right of everyone to canoe the Spey, but limits navigation only to members of the public who have legitimate access to the banks of the river above Knockando. The action arose due to alleged damage to salmon fishing by the passage of canoes. The court had been asked to prevent canoes of Clive’s school from canoeing on the river. Clive won the first judgment, but the matter went to appeal. The appeal was dismissed. More may be heard on this subject yet, but the canoeists’ case was won on the tourist aspect, of public benefit to the valley, in respect of the livelihood of the people who depend upon tourism. It is Clive’s intention to be considerate, as always, to the angling interest and avoid conflict of interest between fishing and canoeing. He believes in live and let live. It is time the estate owners were equally minded. For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.