Tom Weir | Over the Girth Gate

This week saw the official opening of the Borders Railway, which has been closed for 46 years. How fitting, therefore, that our article from Tom Weir’s 1977 archives concerns the Borders Hill-walking Club and some great walks to do in the area…

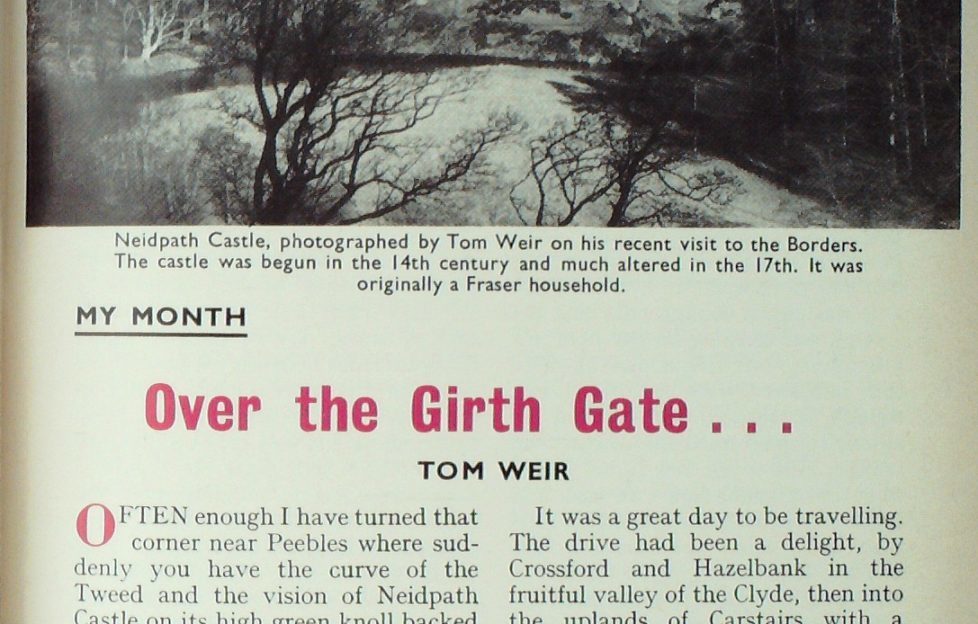

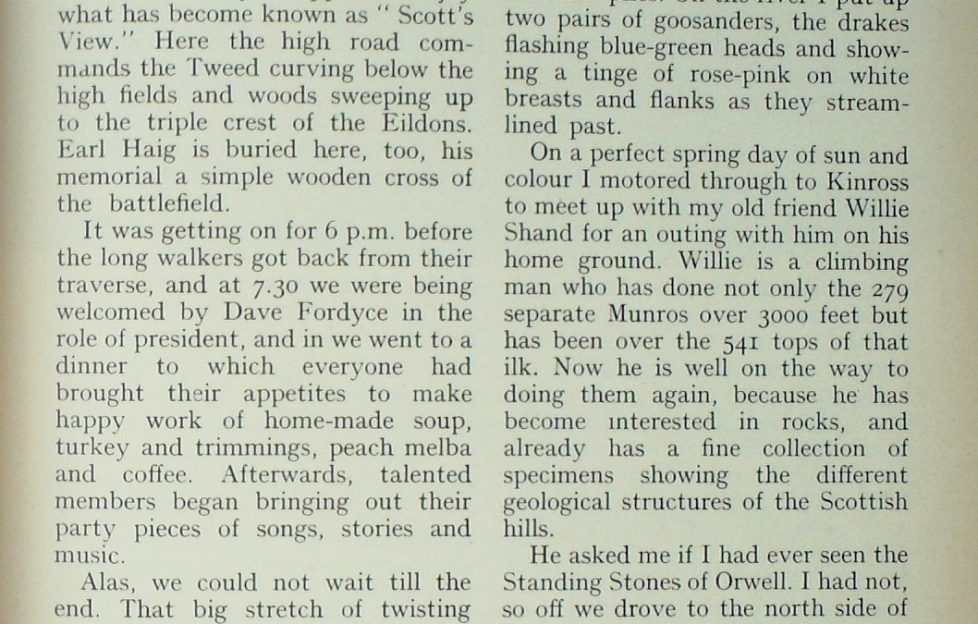

OFTEN enough I have turned that corner near Peebles where suddenly you have the curve of the Tweed and the vision of Neidpath Castle on its high green knoll backed by woods below one of the noblest sweeps of the Border Hills.

But flat lighting has always prevented me from catching it with the camera. Now I had it in my grasp, with the grey tower shining warmly between passing shadows of white cumulus clouds moving across the sun.

And as my camera clicked I could hear the chortling song of a dipper from the river, and see the dot of its snowy chest as it bobbed on a stone.

“It was a great day to be travelling.”

The drive had been a delight, by Crossford and Hazelbank in the fruitful valley of the Clyde, then into the uplands of Carstairs with a tumbling of peewits over bleating lambs where the air was filled with skylark song and birling curlews.

No wonder the “garden centres ” along the route were doing brisk trade. Strange that Clyde and Tweed, running towards different seas, should rise so close to each other as the ancient rhyme says :

Annan, Tweed and Clyde

Rise a out o ae hillside.

Tweed ran, Annan won,

Clyde fell, and broke its neck owre Corralinn.

For us there was a special pleasure in reaching the Tweed, for we were joining up with the Border Hill-walkers for a Sunday outing into unfamiliar territory.

Our immediate destination was Lindean, Selkirk, to spend the night with J. B. Baxter and family, so that we could potter at leisure and enjoy the Saturday afternoon stir of Peebles before taking the road to Traquair. What a peaceful setting these neat Border towns have in river valleys overlooked by green hills and woods!

I took the back road to Yair Bridge, where the river winds under the pointed top of the hill known as “The Three Brethren,” from whose crest stretches the High Minchmuir.

A strong shower was swirling round the tops, and I learned next day from Dave Fordyce, who was up there, that it was savagely squally with snowflakes the size of half-crowns blinding the party.

It was genial enough following the Tweed, and keeping an eye open for kingfishers, but not a blue flash of this brilliant little bird did I see, though I looked and waited at favourite spots until the sun cast an orange glow over the hills.

Heart and Soul of the Hill-walking Club

Grand to get into a snug house at dusk and have an evening talking with the man who has been spearheading the Border Hill-walking Club since its inception in 1974, arranging meetings every fortnight, summer and winter.

J. B. Baxter, known to everybody as “JB” has attended every walk except one.

“Since we formed we’ve covered from Drumelzier in the upper ward of Tweed, to Muckle Cheviot; and from Peel Fell in Liddesdale to Gifford in the Lammermuirs, walking mostly on drove roads, horse tracks, old kirk roads or on open hills. I believe the club satisfies a deeply felt need. We don’t have great stretches of wild country in the Borders—you are never too far from help if you need it. But people need encouragement to go out and explore, for there is so much lonely country. Tracks disappear and reappear. You have to be able to read the map and know what you are doing. The club has been a means of introducing Borderers to their own environment. The average turn-out at any walk is proof of how much they enjoy it. It’s usually about 50.

“Our members range literally from seven to seventy—yes, we have quite a handful of O.A.P’s. Tomorrow, 011 the Girth Gate walk, we’ll have at least eight family groups, husbands, wives and kids. The annual subscription for a family is only £2. You’ll see that there is a choice of a long or short version of the walk tomorrow, and it will divide almost equally between those who want to do the full 18-mile version or less than half of that distance.

“The Girth Gate is not a normal sort of walk. We’ve chosen something unusual because we have to be back for the annual club dinner in the Dry burgh Abbey Hotel. You know, there is a wee bit of a mystery about the Girth Gate. It was the Sanctuary Road, a route over the hills between Melrose Abbey to a Cistercian hospice at Soutra Aisle where the monks offered food and shelter to travellers. There are remnants of ancient tracks, and we hope to link them up. We have no landowner problems, and have never had a cross word in all our stravaigings. Of course, we observe the countryside code, keeping dogs on the lead, closing gates and leaving no litter.”

Following in the footsteps of monks

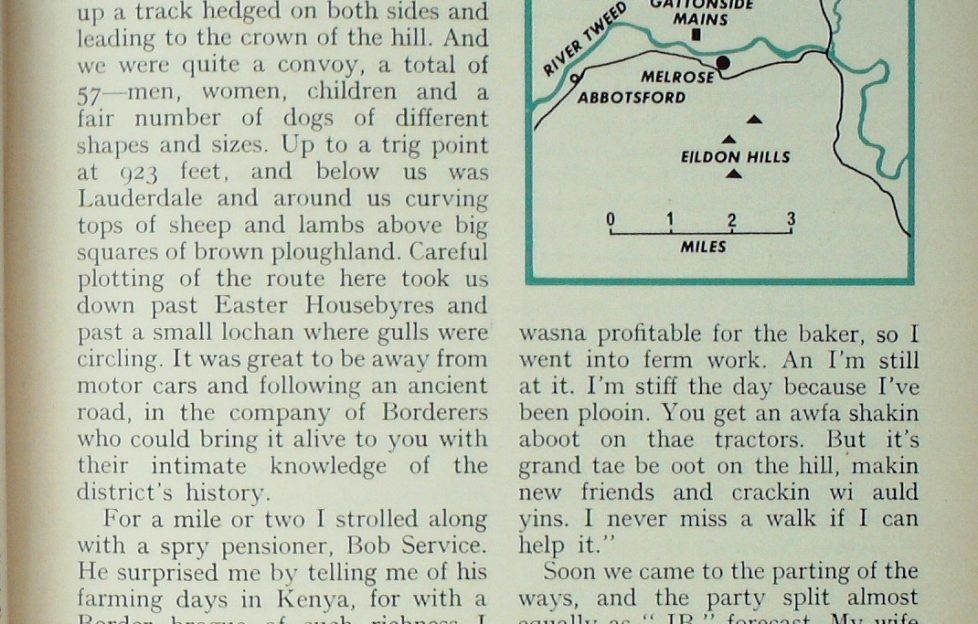

I was looking forward to the walk when next morning we foregathered at Gattonside Mains. The history of the Girth Gate begins right here, for this is where the monks had their orchards, facing south above the Tweed to the Eildons.

“I’ll tell you something that happened here,” said JB. “An old pear tree blew down in a gale and the inside was seen to be of the consistency of calf’s-foot jelly. Perhaps it had been producing fruit as long ago as the 14th century.”

He told me, too, of Threepwood Moss to the north, where the monks cut their peats, and of Blainslie, close to our route, where they had their beehives. The latter place is still notable for honey.

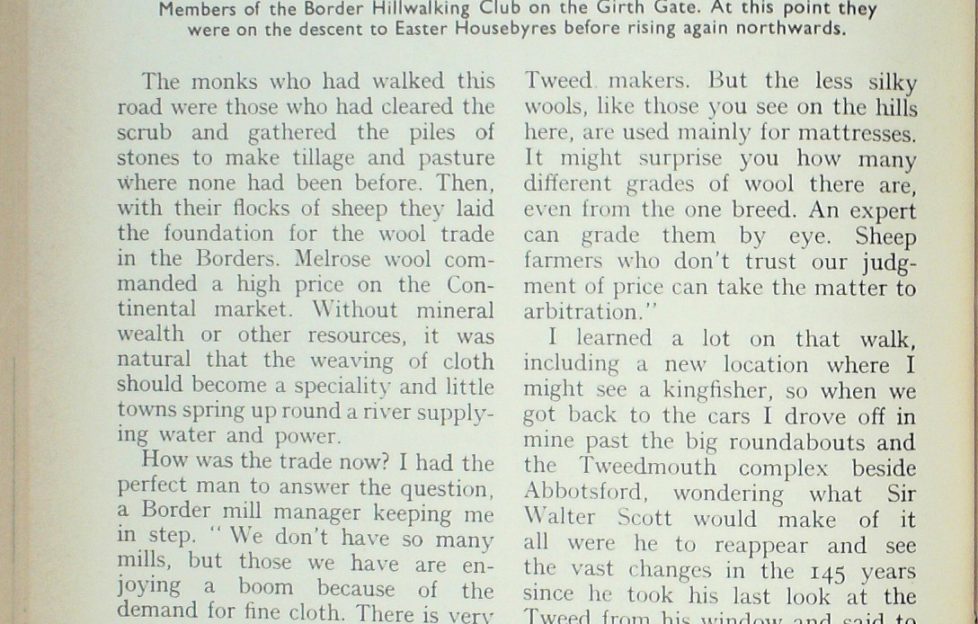

So it was grand to be moving off up a track hedged on both sides and leading to the crown of the hill. And we were quite a convoy, a total of 57—men, women, children and a fair number of dogs of different shapes and sizes. Up to a trig point at 923 feet, and below us was Lauderdale and around us curving tops of sheep and lambs above big squares of brown ploughland.

Careful plotting of the route here took us down past Easter Housebyres and past a small lochan where gulls were circling. It was great to be away from motor cars and following an ancient road, in the company of Borderers who could bring it alive to you with their intimate knowledge of the district’s history.

For a mile or two I strolled along with a spry pensioner, Bob Service. He surprised me by telling me of his farming days in Kenya, for with a Border brogue of such richness I would have thought he had never been away from home.

“Aye, I came hame because of the trouble. It wis nae place for a wife and two kids.

“I had a wee bit money put by, and it wis a guid job, for naebody wantit ye at over fifty. But, man, it wis great to hear the Border tongue again! I got work drivin a laundry van, and I liked it fine, for I got to ken the fowk. Then I did a baker’s round in the oot-lyin places. But it wasna profitable for the baker, so I went into term work. An I’m still at it. I’m stiff the day because I’ve been plooin. You get an awfa shakin aboot on thae tractors. But it’s grand tae be oot on the hill, makin new friends and crackin wi auld yins. I never miss a walk if I can help it.”

Soon we came to the parting of the ways, and the party split almost equally as “JB” forecast. My wife opted for the long walk, but I fancied a more leisurely return, with time to stop and look at flighting redwings, take stock of a passing gaggle of greylag geese, or chat and learn a bit more about the country.

On the ridge crest we were on now we had as landmark the blue tips of the Eildons. And as we undulated over the vast landscape of curving green hills the first sunbursts made the fleeces of the sheep glitter like snow.

The monks who had walked this road were those who had cleared the scrub and gathered the piles of stones to make tillage and pasture where none had been before. Then, with their flocks of sheep they laid the foundation for the wool trade in the Borders.

Melrose wool commanded a high price on the Continental market. Without mineral wealth or other resources, it was natural that the weaving of cloth should become a speciality and little towns spring up round a river supplying water and power.

How was the trade now? I had the perfect man to answer the question, a Border mill manager keeping me in step.

“We don’t have so many mills, but those we have are enjoying a boom because of the demand for fine cloth. There is very little unemployment in our industry, and the prospects for growth looks good.”

He told me that his firm did not now use Border wool for cloth. It comes mainly from New Zealand.

“The Border Leicester-Cheviot crosses you see around you here are produced for their mutton. We buy the wool, and the wool of other breeds from different parts of Scotland, and we send vast quantities of it to Stornoway for the Harris Tweed makers. But the less silky wools, like those you see on the hills here, are used mainly for mattresses. It might surprise you how many different grades of wool there are, even from the one breed. An expert can grade them by eye. Sheep farmers who don’t trust our judgement of price can take the matter to arbitration.”

In seach of a kingfisher

I learned a lot on that walk, including a new location where I might see a kingfisher, so when we got back to the cars I drove off in mine past the big roundabouts and the Tweedmouth complex beside Abbotsford, wondering what Sir Walter Scott would make of it all were he to reappear and see the vast changes in the 145 years since he took his last look at the Tweed from his window and said to his nurse, “Tonight I shall know all.”

The place I was going to was the flat where the battle of Philiphaugh was fought when the great Montrose was routed by the Covenanters and had to take to the hills by crossing the Minch Muir to Traquair.

This stretch is where the kingfisher is often seen, and I thought the prospects of seeing them were good with siskins and goldfinches in canary-like voice on the young pines by the riverside. However, I was out of luck. Maybe the river was too high with recent rain.

My ultimate destination now was Dry burgh Abbey Hotel for the dinner, an ideal spot since just over the wall is the noblest ruin of the Border Abbeys on sloping parkland among fine trees with the Tweed bending round it.

Sir Walter Scott chose to be buried here, and I like the story of his horse at the funeral, coming to a halt at the spot at which its master always stopped to enjoy what has become known as “Scott’s View.”

Here the high road commands the Tweed curving below the high fields and woods sweeping up to the triple crest of the Eildons. Earl Haig is buried here, too, his memorial a simple wooden cross of the battlefield.

It was getting on for 6 p.m. before the long walkers got back from their traverse, and at 7.30 we were being welcomed by Dave Fordyce in the role of president, and in we went to a dinner to which everyone had brought their appetites to make happy work of home-made soup, turkey and trimmings, peach melba and coffee.

Afterwards, talented members began bringing out their party pieces of songs, stories and music.

Alas, we could not wait till the end. That big stretch of twisting road between Dryburgh and Gartocharn had to be faced, so into the rain we went with fond farewells. Visibility got worse and roads became more flooded as we left Carnwath behind us. By next day Ben Lomond had a new cap of snow.

Spring has always a hard light to shake winter from its back. Its official time was the last week of March, but the first bird migrants of summer had jumped the gun by arriving on March 15, three sandpipers fluttering over the water, dipping neatly with their bills as they flew, picking microscopic food particles, while redshanks, in from the Clyde to their nesting territories, gave out their liquid courtship calls, and peewits were corkscrewing their bellies to make scrapes for their eggs.

“I never fail to be astonished at the vitality of nature.”

The air felt wintry, but up on the tops of the trees the herons were perched like gargoyles beside mates incubating, their bodies pressed down and hardly visible in the stick piles. On the river I put up two pairs of goosanders, the drakes flashing blue-green heads and showing a tinge of rose-pink on white breasts and flanks as they streamlined past.

On a perfect spring day of sun and colour I motored through to Kinross to meet up with my old friend Willie Shand for an outing with him on his home ground. Willie is a climbing man who has done not only the 279 separate Munros over 3000 feet but has been over the 541 tops of that ilk. Now he is well on the way to doing them again, because he has become interested in rocks, and already has a fine collection of specimens showing the different geological structures of the Scottish hills.

He asked me if I had ever seen the Standing Stones of Orwell. I had not, so off we drove to the north side of Loch Leven a couple of miles east of Milnathort, and there they were, on a green knowe under the bracken-red slopes of Bishop’s Hill. Probably these two stones are remnants of a circle, dating back 4000 years or more to Bronze Age times.

“Do you know the Puddin Wynd?” asked Willie as we drove into Kinnesswood. “Pull in here and we’ll take a walk up it.”

A short distance uphill and I saw the reason for his question when we came to the cottage where Michael Bruce, the poet of Loch Leven, was born on March 27, 1746.

“There were eight in the family, plus the father and mother, in that wee cottage, times must have been hard. Only three of the children reached adult age. Their father was a weaver, and customers brought in the wool or linen yarn to have their cloth made up. Poverty was the normal state, but at the age of four the future poet could read the Bible. There was no poverty of mind—the father was noted for being a thinker.”

The story of Michael Bruce is of an exceptional lad o’ pairts. A serious youngster, theologically inclined, he had fixed his mind on the ministry.

Like Robert Burns, he had to do some labouring on the land, from which he derived a different kind of inspiration, more towards the melancholy and spiritual.

The poverty of the family seemed insuperable, but by the miracle of a small inheritance of just over £11 Michael was able to set off for Edinburgh University at the age of 16.

At 19 he had gone as far as he could and came home to attend the Theological Hall of the Secession Church at Kinross. They gave him his happiest days, but these were days of trouble within the Church, and the college closed within six months.

For Michael it posed a dilemma. He had to have a job. Teaching was about the only thing open to his training, and the school he went to near Alloa could hardly have been worse, perpetually damp and with an earth floor. Miserable with illness, he walked the 20 miles home to the Puddin Wynd in February 17O7.

His 21st birthday celebrated on March 27 was to be his last. He died of tuberculosis in July, leaving nothing behind except his poetry and the paraphrases he wrote. Here is a fragment of his ode to the cuckoo:

Sweet bird! Thy bower is ever green,

Thy sky is ever clear,

Thou hast no sorrow in thy song,

No winter in thy year!

Alas! Sweet bird! Not so my fate,

Dark scowling skies I see,

Fast gathering round, and fraught with woe

And wintry years to me.

Wintry years indeed. Yet it was at the university he wrote that, when he might have had reason to be optimistic. It is as if his mind penetrated his dark future. No doubt you will remember this fragment of the 19th Paraphrase which are perhaps his best-known lines :

To ploughshares men shall beat their swords

To pruning hooks their spears

Willie Shand was to open up a few more corners of Loch Leven for me that day, but they must wait for another article.

Footnote. -The poetry of Michael Bruce is published by the Michael Brace Memorial Trustees. The cottage of his birth is open to the public in summer as a museum. Literature is on sale there.

Editor’s note: The Michael Bruce Cottage still makes for an interesting visit, and you can find the opening times here.

More from Tom

For the full list of available articles from Tom, click here.