Tom Weir | In Winter Hills

The radio news sounded grim for travellers; warnings of black ice in the Lowlands ; Highland roads difficult with overnight snow and drifting expected…

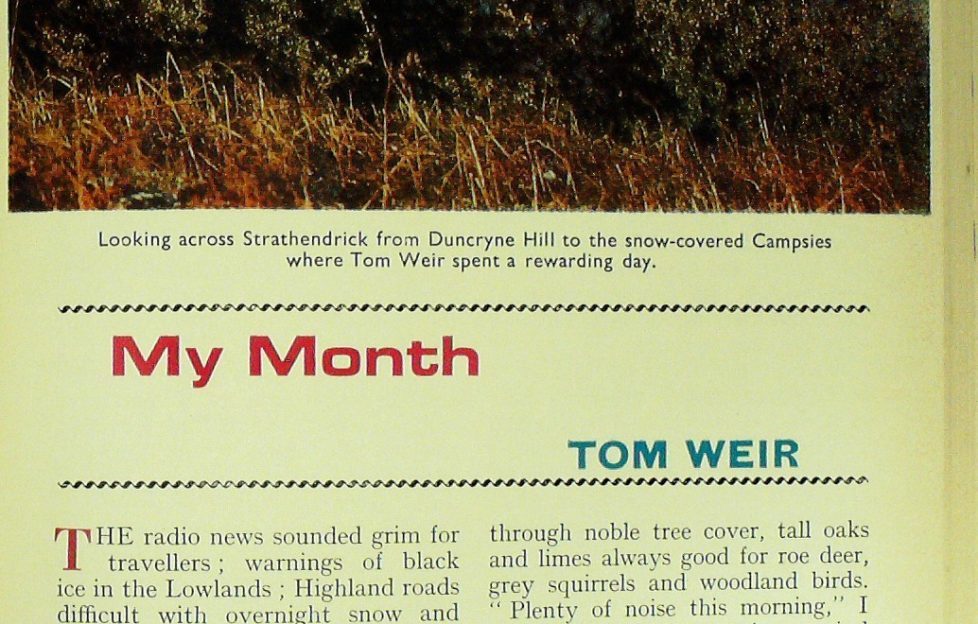

Sitting at home looking out of my windows, I had only to glance north and south to see that it was true. There was something stimulating, though, that wasn’t mentioned—sunshine between the squalls, when the near trees were lit brilliantly against the emerald fields with icing-sugar peaks poking above them.

Just the kind of day to have a walk and look at the hills from the bird marshes of the River Endrick. My way there is a stealthy approach through noble tree cover, tall oaks and limes always good for roe deer, grey squirrels and woodland birds.

“Plenty of noise this morning,” I was thinking, sorting out in my mind the trumpeting of whooper swans from the massed baying of greylag geese and the whistles and yelps of wigeon and teal.

As I crept closer, suddenly I had company, a charm of fourteen goldfinches on the alders above my head, picking at the catkins and letting out engaging little snatches of song from time to time. They flew off when they were joined by a swarm of redpolls and a few chaffinches.

Next was a jay, followed by another and another, until six all crossed the same clearing to give me excellent views of their rich cinnamon and pink, patched with exotic blue, black and white. The unusual feature was that each had something in its bill, undoubtedly acorns which they would no doubt bury somewhere and then forget about. In this way oak trees grow up where they otherwise would not. Then came a stinging shower of sleet, not troublesome to me because of my tree cover, and beautifully timed, for when I came to the edge of the marsh the discharging clouds were broken and the snowpeaks of Luss and the top of Ben Lomond were bursting through.

An Aerial Performance

Nature was about to lay on a performance, and I played a part in it, first because I had overlooked a number of Greenland white-fronted geese which rose in musical alarm, alerting a great concourse of birds that sprang from the reeds and open water. Mallard, shoveller, wigeon, teal, and golden-eye all whirled into the air followed by a thunder of wings and a wave of clamouring sound from a thousand greylags invisible to me until that moment.

All that was needed now was the stage lighting, and it came in a burst of full sun, bringing all the bird-book colours to whirling life. It was the last birds to rise which stole the show, though. A string of trumpeting whooper swans flew across my path in line, long necks outstretched, white wings flashing like bedsheets on a line, whiter than white because of the black sky behind their dazzle.

That should have been enough for one morning, but as I crunched through the thin ice skinning the frozen pools my eye was attracted to a crow mobbing a high-flying falcon superficially like a kestrel. I had put the glass on it and was in the act of changing my mind to peregrine when down it plummeted in a wings-folded stoop—whoosh !— and I had a perfect view of it missing its prey—a pheasant which dropped so swiftly to ground that the peregrine had to straighten out for lack of air space.

For me that was a first. I’ve never had an exhibition of a peregrine stooping close to me before. I strolled towards the bank of the Endrick, and as I got there a cock hen harrier came flying over as if to meet me, face rounded and owl-like, long grey wings tipped with black, a bunting bird flickering buoyantly around me, doing constant about-turns never farther than a few feet above the reeds. It broke off and went elsewhere when it was buzzed by some passing peewits.

By afternoon the weather was changing. There was no sun and the cloud layer had come down on the hills, but after dark a keen frost set in and the stars were sparkling before I went to bed and I anticipated that a good day would follow. I hardly expected such an absolute cracker lasting from yellow dawn to red sunset.

The Campsies Beckoned

No long drive for me on such a day. The Campsies beckoned, and off I went with friend Les to the Corrie of Balglass three miles from Fintry to climb Earl’s Seat from the steep north front which drops to Strathendrick. I’ve always thought of this corrie as having Cairngorm character by reason of its wide, horseshoe sweep rimmed with rock. It was a favourite place of my early bird-watching career when its nesting oyster- catchers, peewits, curlews, grey wagtails, wheatears and meadow pipits excited me greatly. To get there I used to cycle out from the north of Glasgow by the Blane Valley.

In winter, the approach was different. Bus to Blanefield, and then we would go up the rocks of Slackdhu and from 1600 feet strike north for an hour over Clachertyfarlie Knowes, rough going to the indeterminate point of the Earl, and scene of a few adventures. The worst was when we were caught out in a blizzard, an immediate whiteout and such an assault of whirling snowflakes that it was impossible to read a map.

We had to depend on hitting the march fence which we knew lay across our path, and turning along it to reach the top. We got there, but getting back against the blizzard was utterly demoralising, not an inch of shelter, and we were sinking into drifts and beginning to feel despair. There was no knowing if we had lost the way. A wee clearing showed we were indeed off-course. We got down, but we were as near to exhaustion as we had ever been. It was a hard lesson.

By contrast, here were the winter campsies at their benign best, Strathendrick alight with colour, its hills and woods a swelling green pattern against the backdrop of icing-sugar peaks stretching from Loch Lomond and the Arrochar Peaks to the big Perthshire Bens. In fact, from Ben More, Cowal, to Ben Chonzie.

Walking In The Shade

To step from the warm sun of the lower hillside into the shadowy corrie was like going into a fridge, everything iron-hard, screes frozen and boulders sprinkled with crisp snow. It induced a good turn of speed in the invigorating air, but even so, we could hardly wait to get to the top of the narrow gully we took, for its throat was rimmed with a glittering necklace caught by the sun.

What a moment when in a single step we were out of shadow into the warming blaze and perching on the airy point of Allanrowie, 1568 feet, with the most shapely aspect of Earl’s Seat about one mile distant across the snow!

Lovely walking, everything crisp, and mountain hares looking grey in a white world shared only by cackling grouse and a barking raven. Soon we were on the highest point, looking out on the dark hump of Ailsa Craig and the higher serrations of the Arran hills. Glasgow seemed very close. The new multi-storeys of Springburn pinpointed where I used to live. No wonder the cycle runs of yore did not seem so very long!

The relationship between the Highlands and the Lowlands can be studied from the top of the Earl’s Seat. From Loch Lomond it was easy to see why the cattle drovers heading for Falkirk turned along the foot of the Campsies by Killearn and Balfron to Fintry. From the Trossachs hills they were more immediately on to low ground, the peat morass of Flanders Moss spanned by the deep, sluggish Forth which they crossed by the Fords of Frew to get into the Canon Valley. The knowledge of topography these men carried in their heads is something to marvel at.

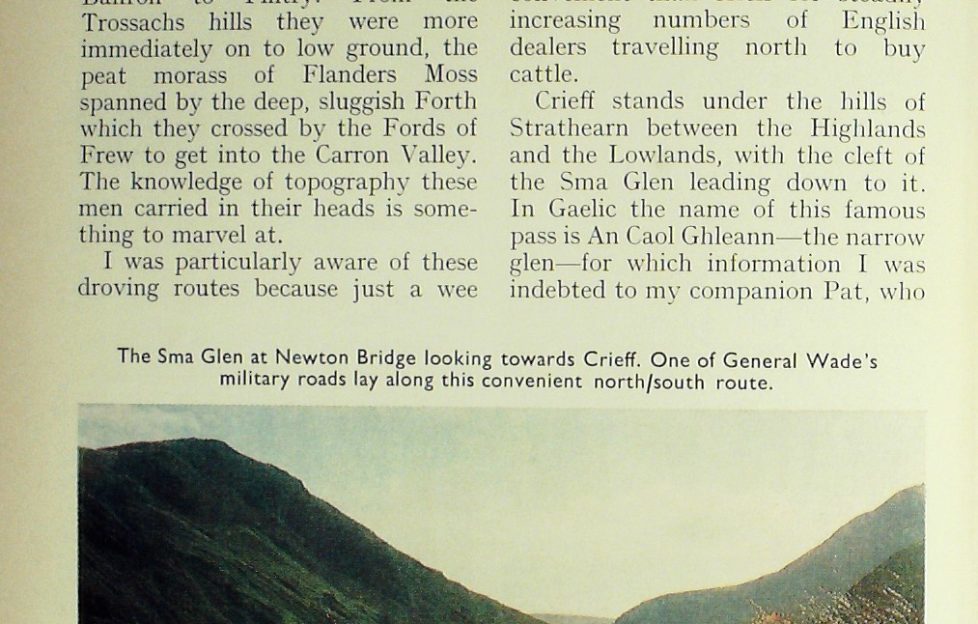

I was particularly aware of these droving routes because just a wee while earlier I had made a pilgrimage with Pat Sandeman over one of the most famous of all droving routes from Aberfeldy to Crieff by the Sma Glen. In the great cattle market story which began in the 17th century, Crieff was the main centre until the early 19th century. Why the changeover? Because of the growth of London and the Midlands of England and the demand for Highland beef by the army and navy engaged in the French wars, Falkirk was more convenient than Crieff for steadily increasing numbers of English dealers travelling north to buy cattle.

Crieff stands under the hills of Strathearn between the Highlands and the Lowlands, with the cleft of the Sma Glen leading down to it. In Gaelic the name of this famous pass is An Caol Ghleann—the narrow glen—for which information I was indebted to my companion Pat, who was acting as guide. Our plan was to look for the original road which General Wade built, not for the cattle trade, but to maintain law and order in the time of Jacobite unrest between 1715 and 1746.

The present motor road follows the rough line of Wade’s road. After going through Crieff it is on the other side of the golf course, which is to the left, but when you turn uphill to Monzie it is on your right and this is a good place to stop and take account of one of the great views of Perthshire, over Monzie Castle and its woods and rolling greenery to the shaggy peak of Ben Vorlich.

Soon the rugged arrows of the glen close in, and for four miles you have the river below and dark rocks and screes frowning down on you. The photograph below was taken that day and looks south, towards Crieff.

This is the turning point of the glen, for the river swings away west offering a natural pass to Ardtalnaig on Loch Tay, while the Wade road climbs north and can be picked out on the hillside to your left as you drive to Amulree.

Down into Strath Bran we now swung north-west into Glen Cochill, stopping at 1000 feet to marvel at one of the small Wade bridges on the grassy track to our left. Past wee Loch na Graige at 1400 feet and we were on the descent to Aberfeldv for a look at the greatest of all Wade’s bridges, the one that still carries modern traffic across the Tay.

In his nine years of active military road-making, Wade built from 30 to 40 bridges, all of them small, except this one in which the main arch of live is 60 feet, and he completed it in eight months. It was the key point on the route from Dalnacardoch to Crieff, and until it was built the only way across the Tay here was by ferryboat. An inscription cut in the stonework of the bridge reads :

AT THE COMMAND OF

HIS MAJTY KING GEORGE 2ND

THIS BRIDGE WAS ERECTED IN THE YEAR 1733

THIS WITH THE ROADS AND OTHER

MILITARY WORKS FOR SECURING

A SAFE AND EASY COMMUNICATION

BETWEEN THE HIGH LANDS AND

THE TRADING TOWNS IN THE LOW

COUNTRY WAS BY HIS MAJTY

COMMITTED TO THE CARE OF LIEUT

GENERAL GEORGE WADE

COMMANDER IN CHIEF OF THE FORCES

IN SCOTLAND WHO LAID THE FIRST

STONE OF THIS BRIDGE ON THE

2 3RD OF APRIL AND FINISHED THE

WORK IN THE SAME YEAR.

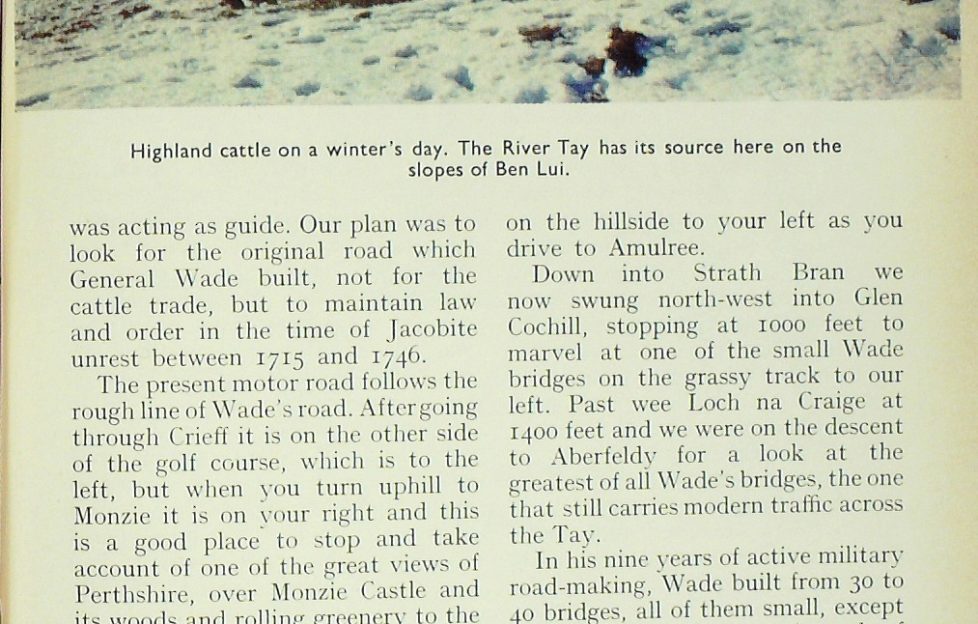

The photograph on page 537 (fourth in gallery) was taken much farther up the Tay, near Tyndrum, as the hungry kyloes were being fed their hay under the north-east corrie of Ben Lui, 3708 feet. This is the source of our longest river, length 119¾ miles, which is spanned by another famous bridge at Dunkeld, built in 1809 by another great road-builder—Thomas Telford.

Pat and I were thinking of both Telford and Wade as we drove from Aberfeldy on the new A9 which eliminates the necessity of crossing the Telford Bridge at Dunkeld by keeping to the west bank of the Tay.

We thought of them because across the river was the A9, built by Telford, and just below it under the rocky hill called Craigiebarns was a section of the original Wade road. By building his bridge at Dunkeld, Telford had eliminated the nuisance of a ferry crossing and enabled the first direct stage-coach service to be run between Inverness and Perth. The time taken was 10 hours. The Scottish engineer had built for wheels drawn by horses, yet his work was so good that his road coped with every change from motor car to juggernaut for the best part of 160 years.

The new A9 has its critics, because only 20 miles of it are dual carriageway, but I am not one of them. I think it is good enough, especially when you think of the tourist traffic which will debouch from it on to single-track Highland roads. Better to make the transition gradually, I think. The increasing number of accidents in Ross and Sutherland today is due to modern motorists being familiar only with broad roads.

Hopping Deer

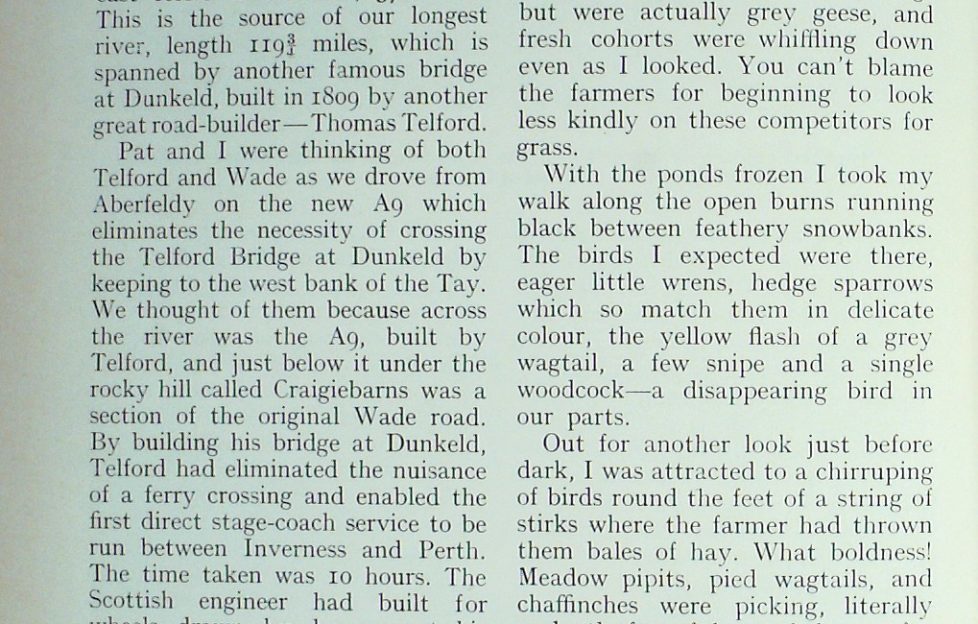

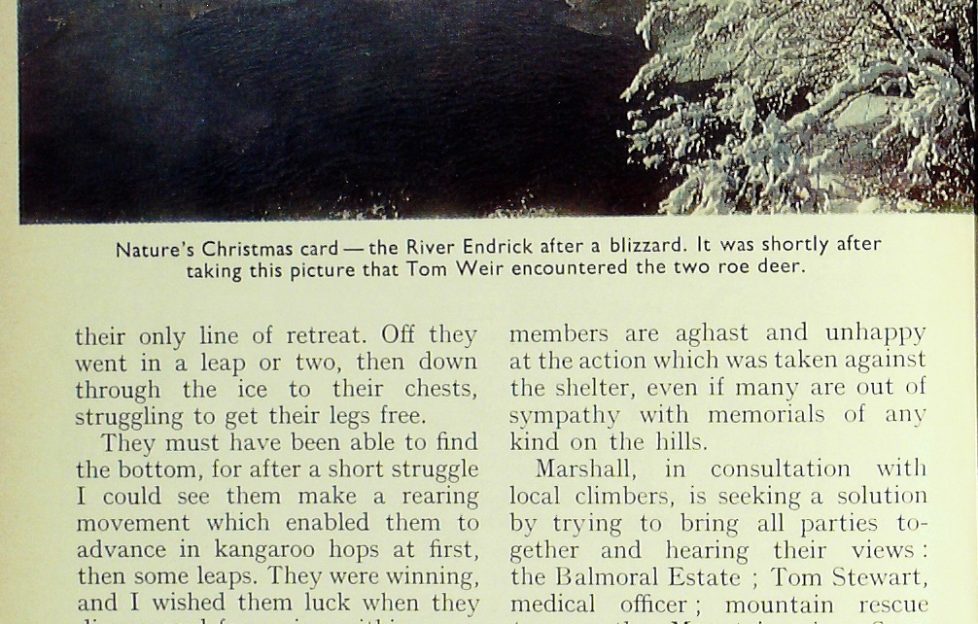

I was glad not to be motoring any distance when I took the picture of snow on the Endrick after a big overnight fall blanketing the ice on the roads and causing our postman to crash his van. Even my own little hill, Duncryne, was slippery, with a wee snow cornice on top ! Below me was a field peppered with black birds that looked like starlings but were actually grey geese, and fresh cohorts were whiffling down even as I looked. You can’t blame the farmers for beginning to look less kindly on these competitors for grass.

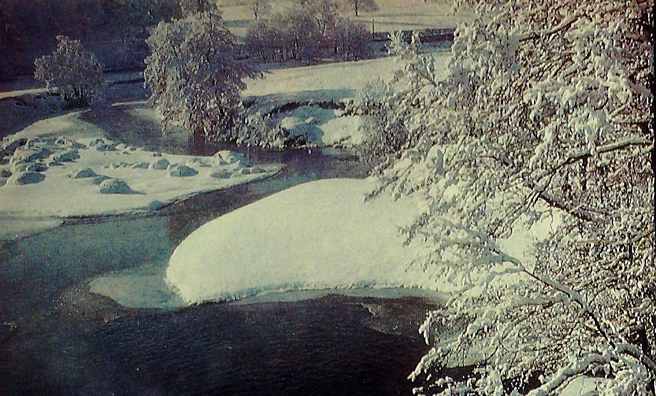

With the ponds frozen I took my walk along the open burns running black between feathery snowbanks.

The birds I expected were there, eager little wrens, hedge sparrows which so match them in delicate colour, the yellow flash of a grey wagtail, a few snipe and a single woodcock—a disappearing bird in our parts.

Out for another look just before dark, I was attracted to a chirruping of birds round the feet of a string of stirks where the farmer had thrown them bales of hay. What boldness! Meadow pipits, pied wagtails, and chaffinches were picking, literally under the feet of the cattle beasts, for the dropped seeds in the blackened, snow-churned mud.

The strangest sighting of that day had been a pair of roe deer. As I was emerging from the edge of a thick wood, within which gunshots had been firing, I saw them stand uncertainly as if wondering where to run. The river bank was fairly near, but in front of it was an obstacle of flood water, frozen thinly over and blanketed with snow. Without going back into the wood, it was their only line of retreat. Off they went in a leap or two, then down through the ice to their chests, struggling to get their legs free.

They must have been able to find the bottom, for after a short struggle I could see them make a rearing movement which enabled them to advance in kangaroo hops at first, then some leaps. They were winning, and I wished them luck when they disappeared from view within range of the River Endrick.

Last month I wrote about the destruction by unknown vandals of the tiny shelter being built in the corrie of Lochnagar. Bill Marshall, of Aberdeen, a respected climber and mountain rescue man, is hoping for a much happier outcome in this whole matter. He has been telling me that Aberdeen Climbing Club members are aghast and unhappy at the action which was taken against the shelter, even if many are out of sympathy with memorials of any kind oil the hills.

Marshall, in consultation with local climbers, is seeking a solution by trying to bring all parties together and hearing their views: the Balmoral Estate ; Tom Stewart, medical officer; mountain rescue teams; the Mountaineering Committee of Scotland and the Niven brothers who formulated the plan and who built the structure which was destroyed by objectors unknown.

The very important thing and the reassuring aspect is that no Climbing Club member had a hand in destroying that bothy. The outcome is likely to be a plan to build a small hut and provide a better first-aid box than the present one.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday!

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.